Utente:Vituzzu/i

| Guerra di liberazione bengalese parte Guerra fredda | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Data | 26 marzo - 16 dicembre 1971 | ||

| Luogo | Pakistan Orientale | ||

| Casus belli | Operazione Searchlight del governo pakistano contro il movimento nazionalista bengalese | ||

| Esito | vittoria del Mukti Bahini e degli alleati indiani | ||

| Schieramenti | |||

| Comandanti | |||

| Effettivi | |||

| Perdite | |||

| Civili uccisi: 300.000-3.000.000 (stimati)[7][8] | |||

| Voci di guerre presenti su Wikipedia | |||

Template:Campaignbox Bangladesh Liberation War Template:Campaignbox Indo-Pakistani War of 1971

La Guerra di liberazione del Bangladesh(i) (Template:Lang-bn Muktijuddho) fu un conflitto armato che vide schierati Pakistan dell'Est ed India contro Pakistan dell'Ovest. La guerra diede origine alla secessione del Pakistan dell'Est, che divenne il Bangladesh indipendente.

The war broke out on 26 March 1971 as army units directed by West Pakistan launched a military operation in East Pakistan against Bengali civilians, students, intelligentsia, and armed personnel who were demanding separation of the East from West Pakistan. Bengali military, paramilitary, and civilians formed the Mukti Bahini (Template:Lang-bn "Liberation Army") and used guerrilla warfare tactics to fight against the West Pakistan army. India provided economic, military and diplomatic support to the Mukti Bahini rebels, leading Pakistan to launch Operation Chengiz Khan, a pre-emptive attack on the western border of India which started the Indo-Pakistani War of 1971.

On 16 December 1971, the allied forces of the Indian army and the Mukti Bahini defeated the West Pakistani forces deployed in the East. The resulting surrender was the largest in number of prisoners of war since World War II.

Background[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

In August 1947, the Partition of British India gave birth to two new states; a secular state named India and an Islamic state named Pakistan. But Pakistan comprised two geographically and culturally separate areas to the east and the west of India. The western zone was popularly (and for a period of time, also officially) termed West Pakistan and the eastern zone (modern-day Bangladesh) was initially termed East Bengal and later, East Pakistan. Although the population of the two zones was close to equal, political power was concentrated in West Pakistan and it was widely perceived that East Pakistan was being exploited economically, leading to many grievances.

On 25 March 1971, rising political discontent and cultural nationalism in East Pakistan was met by brutal[9] suppressive force from the ruling elite of the West Pakistan establishment[10] in what came to be termed Operation Searchlight.[11]

The violent crackdown by West Pakistan forces[12] led to East Pakistan declaring its independence as the state of Bangladesh and to the start of civil war. The war led to a sea of refugees (estimated at the time to be about 10 million)[13][14] flooding into the eastern provinces of India[13]. Facing a mounting humanitarian and economic crisis, India started actively aiding and organizing the Bangladeshi resistance army known as the Mukti Bahini.

East Pakistani grievances[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Disparità economiche[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Malgrado fosse maggiormente popolato, il Pakistan orientale riceveva una frazione del budget dello Stato inferiore a quella della regione occidentale.

| Anno | Fondi destinati al Pakistan occidentale (in crore, decine di milioni, di rupie pakistane) | Fondi destinati al Pakistan orientale (in crore di rupie) | Percentuale di spesa all'est rispetto a quella all'ovest |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1950–55 | 1,129 | 524 | 46.4 |

| 1955–60 | 1,655 | 524 | 31.7 |

| 1960–65 | 3,355 | 1,404 | 41.8 |

| 1965–70 | 5,195 | 2,141 | 41.2 |

| Totale | 11,334 | 4,593 | 40.5 |

| Fonte: Rapporto della commissione di sorveglianza sul quarto piano quinquennale del 1970-75, Vol. I, pubblicato dalla commissione di pianificazione del Pakistan | |||

Political differences[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Although East Pakistan accounted for a slight majority of the country's population,[15] political power remained firmly in the hands of West Pakistanis. Since a straightforward system of representation based on population would have concentrated political power in East Pakistan, the West Pakistani establishment came up with the "One Unit" scheme, where all of West Pakistan was considered one province. This was solely to counterbalance the East wing's votes. After the East broke away to form Bangladesh, the Punjab province insisted that politics in West Pakistan now be decided on the basis of a straightforward vote, since Punjabis were more numerous than the other groups, such as Sindhis, Pashtuns, or Balochs.

After the assassination of Liaquat Ali Khan, Pakistan's first prime minister, in 1951, political power began to be concentrated in the President of Pakistan, and eventually, the military. The nominal elected chief executive, the Prime Minister, was frequently sacked by the establishment, acting through the President.

East Pakistanis noticed that whenever one of them, such as Khawaja Nazimuddin, Muhammad Ali Bogra, or Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy were elected Prime Minister of Pakistan, they were swiftly deposed by the largely West Pakistani establishment. The military dictatorships of Ayub Khan (27 October 1958 – 25 March 1969) and Yahya Khan (25 March 1969 – 20 December 1971), both West Pakistanis, only heightened such feelings.

The situation reached a climax when in 1970 the Awami League, the largest East Pakistani political party, led by Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, won a landslide victory in the national elections. The party won 167 of the 169 seats allotted to East Pakistan, and thus a majority of the 313 seats in the National Assembly. This gave the Awami League the constitutional right to form a government. However, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto (a Sindhi), the leader of the Pakistan Peoples Party, refused to allow Rahman to become the Prime Minister of Pakistan. Instead, he proposed the idea of having two Prime Ministers, one for each wing. The proposal elicited outrage in the east wing, already chafing under the other constitutional innovation, the "one unit scheme". Bhutto also refused to accept Rahman's Six Points. On 3 March 1971, the two leaders of the two wings along with the President General Yahya Khan met in Dhaka to decide the fate of the country. Talks failed. Sheikh Mujibur Rahman called for a nation-wide strike.

On 7 March 1971, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman (soon to be the prime minister) delivered a speech at the Racecourse Ground (now called the Suhrawardy Udyan). In this speech he mentioned a further four-point condition to consider the National Assembly Meeting on 25 March:

- The immediate lifting of martial law.

- Immediate withdrawal of all military personnel to their barracks.

- An inquiry into the loss of life.

- Immediate transfer of power to the elected representative of the people before the assembly meeting 25 March.

He urged "his people" to turn every house into a fort of resistance. He closed his speech saying, "Our struggle is for our freedom. Our struggle is for our independence." This speech is considered the main event that inspired the nation to fight for their independence. General Tikka Khan was flown in to Dhaka to become Governor of East Bengal. East-Pakistani judges, including Justice Siddique, refused to swear him in.

Between 10 and 13 March, Pakistan International Airlines cancelled all their international routes to urgently fly "Government Passengers" to Dhaka. These "Government Passengers" were almost all Pakistani soldiers in civilian dress. MV Swat, a ship of the Pakistani Navy, carrying ammunition and soldiers, was harboured in Chittagong Port and the Bengali workers and sailors at the port refused to unload the ship. A unit of East Pakistan Rifles refused to obey commands to fire on Bengali demonstrators, beginning a mutiny of Bengali soldiers.

Squilibrio militare[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

I bengalesi erano sotto rappresentati in seno all'esercito pakistano. Gli ufficiali di origine bengalese nei diversi settori dell'esercito erano infatti solo il 5% dell'organico del 1965, solo una piccola parte di essi occupavano posti di comando, mentre la maggior parte ricoprivano ruoli tecnici o amministrativi.[16] I pakistani occidentali erano convinti che i bengalesi non avessero "attitudine militare" al contrario dei Pashtun e degli abitati nel Punjab; la teoria delle razze marziali fu presto messa da parte come ridicola ed umiliante, tuttavia i bengalesi[16] malgrado le alte spese militari dello stato unitario il Pakistan orientale non ricevette alcun beneficio in termini di contratti, acquisti e commesse militari. La guerra indo-pakistana del 1965 sul Kashmir mise in risalto il senso di insicurezza militare dei bengalesi: la difesa del Pakistan orientale fu affidata soltanto ad una divisione di fanteria a ranghi incompleti ed a 15 aerei da combattimento, senza alcuna presenza di forze corazzate.[17][18]

Controversia linguistica[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Nel 1948, Mohammad Ali Jinnah primo governatore generale del Pakistan dichiaro a Dacca che "l'Urdu e solo l'Urdu" sarebbe stata l'unica lingua ufficiale dell'intero Pakistan.[19] Ciò a dimostrazione della tensione fra i vari gruppi visto che l'Urdu era parlato ad occidente solo dai Muhajir e ad oriente solo dai Bihari, la maggioranza della popolazione occidentale era di lingua Punjabi, mentre la maggioranza di quella orientale era di lingua bengalese.[20] La controversia linguistica raggiunse l'acme durante una serie di rivolte bengalesi, molti studenti e civili persero la vita negli scontri contro la polizia del 21 febbraio 1952.[20] The day is revered in Bangladesh and in West Bengal as the Language Martyrs' Day. Later, in memory of the 1952 killings, UNESCO declared 21 February as the International Mother Language Day in 1999.[21]

Nel Pakistan occidentale le rivendicazioni linguistiche furono viste come una rivolta particolarista contro gli interessi dello Stato pakistano[22] e contro l'ideologia di base del Pakistan: la "teoria delle due Nazioni"[23], i politici occidentali consideravano la lingua Urdu come un prodotto della cultura islamica indiana,[24] come affermato da Ayub Khan nel 1967, "I bengalesi orientali... sono ancora influenzati considerevolmente dalla cultura Hindu."[24] Ma i morti hanno portato a risentimenti che furono uno dei maggiori fattori nella ricerca dell'indipendenza.[23][24]

Response to the 1970 cyclone[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

The 1970 Bhola cyclone made landfall on the East Pakistan coastline during the evening of 12 November, around the same time as a local high tide,[25] killing an estimated 300,000 to 500,000 people. Though the exact death toll is not known, it is considered the deadliest tropical cyclone on record.[26] A week after the landfall, President Khan conceded that his government had made "slips" and "mistakes" in its handling of the relief efforts for a lack of understanding of the magnitude of the disaster.[27]

A statement released by eleven political leaders in East Pakistan ten days after the cyclone hit charged the government with "gross neglect, callous indifference and utter indifference". They also accused the president of playing down the magnitude of the problem in news coverage.[28] On 19 November, students held a march in Dhaka protesting the slowness of the government response.[29] Maulana Abdul Hamid Khan Bhashani addressed a rally of 50,000 people on 24 November, where he accused the president of inefficiency and demanded his resignation.

As the conflict between East and West Pakistan developed in March, the Dhaka offices of the two government organisations directly involved in relief efforts were closed for at least two weeks, first by a general strike and then by a ban on government work in East Pakistan by the Awami League. With this increase in tension, foreign personnel were evacuated due to fears of violence. Relief work continued in the field, but long-term planning was curtailed.[30] This conflict widened into the Bangladesh Liberation War in December and concluded with the creation of Bangladesh. This is one of the first times in modern history that a natural event helped to trigger a civil war.[31]

Operation Searchlight[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

A planned military pacification carried out by the Pakistan Army — codenamed Operation Searchlight — started on 25 March to curb the Bengali nationalist movement[32] by taking control of the major cities on 26 March, and then eliminating all opposition, political or military,[33] within one month. Before the beginning of the operation, all foreign journalists were systematically deported from East Pakistan.[34]

The main phase of Operation Searchlight ended with the fall of the last major town in Bengali hands in mid-May. The operation also began the 1971 Bangladesh atrocities. These systematic killings served only to enrage the Bengalis, which ultimately resulted in the secession of East Pakistan later in the same year. The international media and reference books in English have published casualty figures which vary greatly, from 5,000–35,000 in Dhaka, and 200,000–3,000,000 for Bangladesh as a whole.[7][35]

According to the Asia Times,[36]

At a meeting of the military top brass, Yahya Khan declared: "Kill 3 million of them and the rest will eat out of our hands." Accordingly, on the night of 25 March, the Pakistani Army launched Operation Searchlight to "crush" Bengali resistance in which Bengali members of military services were disarmed and killed, students and the intelligentsia systematically liquidated and able-bodied Bengali males just picked up and gunned down.

Although the violence focused on the provincial capital, Dhaka, it also affected all parts of East Pakistan. Residential halls of the University of Dhaka were particularly targeted. The only Hindu residential hall — the Jagannath Hall — was destroyed by the Pakistani armed forces, and an estimated 600 to 700 of its residents were murdered. The Pakistani army denies any cold blooded killings at the university, though the Hamood-ur-Rehman commission in Pakistan concluded that overwhelming force was used at the university. This fact and the massacre at Jagannath Hall and nearby student dormitories of Dhaka University are corroborated by a videotape secretly filmed by Prof. Nurul Ullah of the East Pakistan Engineering University, whose residence was directly opposite the student dormitories.[37]

Hindu areas suffered particularly heavy blows. By midnight, Dhaka was literally burning,[senza fonte] especially the Hindu dominated eastern part of the city. Time magazine reported on 2 August 1971, "The Hindus, who account for three-fourths of the refugees and a majority of the dead, have borne the brunt of the Pakistani military hatred."

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was arrested by the Pakistani Army. Yahya Khan appointed Brigadier (later General) Rahimuddin Khan to preside over a special tribunal prosecuting Mujib with multiple charges. The tribunal's sentence was never made public, but Yahya caused the verdict to be held in abeyance in any case.[senza fonte] Other Awami League leaders were arrested as well, while a few fled Dhaka to avoid arrest. The Awami League was banned by General Yahya Khan.[38]

Declaration of independence[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

The violence unleashed by the Pakistani forces on 25 March 1971, proved the last straw to the efforts to negotiate a settlement. Following these outrages, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman signed an official declaration that read:

Today Bangladesh is a sovereign and independent country. On Thursday night, West Pakistani armed forces suddenly attacked the police barracks at Razarbagh and the EPR headquarters at Pilkhana in Dhaka. Many innocent and unarmed have been killed in Dhaka city and other places of Bangladesh. Violent clashes between E.P.R. and Police on the one hand and the armed forces of Pakistan on the other, are going on. The Bengalis are fighting the enemy with great courage for an independent Bangladesh. May Allah aid us in our fight for freedom. Joy[39] Bangla.[40]

Sheikh Mujib also called upon the people to resist the occupation forces through a radio message.[41] Mujib was arrested on the night of 25–26 March 1971 at about 1:30 a.m. (as per Radio Pakistan’s news on 29 March 1971).

A telegram containing the text of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman's declaration reached some students in Chittagong. The message was translated to Bangla by Dr. Manjula Anwar. The students failed to secure permission from higher authorities to broadcast the message from the nearby Agrabad Station of Radio Pakistan. They crossed Kalurghat Bridge into an area controlled by an East Bengal Regiment under Major Ziaur Rahman. Bengali soldiers guarded the station as engineers prepared for transmission. At 19:45 hrs on 27 March 1971, Major Ziaur Rahman broadcast announcement of the declaration of independence on behalf of Sheikh Mujibur. On 28 March Major Ziaur Rahman made another announcement,which is as follows:

This is Shadhin Bangla Betar Kendro. I, Major Ziaur Rahman, at the direction of Bangobondhu sheikh Mujibur Rahman, hereby declare that the independent People's Republic of Bangladesh has been established. At his direction, I have taken command as the temporary Head of the Republic. In the name of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, I call upon all Bengalis to rise against the attack by the West Pakistani Army. We shall fight to the last to free our Motherland. By the grace of Allah, victory is ours. Joy Bangla. Audio of Zia's announcement (interview - Belal Mohammed)

The Kalurghat Radio Station's transmission capability was limited. The message was picked up by a Japanese ship in Bay of Bengal. It was then re-transmitted by Radio Australia and later by the British Broadcasting Corporation.

M A Hannan, an Awami League leader from Chittagong, is said to have made the first announcement of the declaration of independence over the radio on 26 March 1971[42]. There is controversy now as to when Major Zia gave his speech. BNP sources maintain that it was 26 March, and there was no message regarding declaration of independence from Mujibur Rahman. Pakistani sources, like Siddiq Salik in Witness to Surrender had written that he heard about Mujibor Rahman's message on the Radio while Operation Searchlight was going on, and Maj. Gen. Hakeem A. Qureshi in his book The 1971 Indo-Pak War: A Soldier's Narrative, gives the date of Zia's speech as 27 March 1971[43].

26 March 1971 is considered the official Independence Day of Bangladesh, and the name Bangladesh was in effect henceforth. In July 1971, Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi openly referred to the former East Pakistan as Bangladesh.[44] Some Pakistani and Indian officials continued to use the name "East Pakistan" until 16 December 1971.

Liberation war[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Da marzo a giugno[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Una prima resistenza fu spontanea e disorganizzata, non si credeva perciò che potesse durare a lungo.[45] Tuttavia quando l'esercito pakistano iniziò a vessare la popolazione la resistenza iniziò a crescere, l'attività del Mukti Bahini crebbe rapidamente. I pakistani cercarono di stroncare il movimento, tuttavia un crescente numero di soldati di origine bengalese iniziarono a defezionare in favore dell'esercito clandestino, tali forze si fusero col Mukti Bahini ricevendo forniture militari dall'India. La risposta pakistana consistette nel paracadutare due divisioni di fanteria ed in una contestuale riorganizzazione delle proprie forze oltre che nell'organizzazione delle forze paramilitari dei Razakar, degli Al-Badrs e degli Al-Shams (che erano in gran parte membri della Lega Musulmana, il partito di governo, e di altri gruppi islamici), oltre che di altri bengalesi che si opponevano all'indipendenza, come i musulmani Bihar stabilitisi nel Bengala nel corso della divisione dell'India britannica.

Il 17 aprile 1971 si formò un governo provvisorio nel distretto di Meherpur al confine con l'India con Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, detenuto in Pakistan, come presidente, Syed Nazrul Islam presidente pro-tempore e Tajuddin Ahmed come primo ministro. Con l'intensificarsi degli scontri fra pakistani e Mukti Bahini circa 10 milioni di persone, principalmente hindu, cercarono rifugio negli stati indiani dell'Assam e del Bengala occidentale.[46]

June – September[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Bangladesh forces command was set up on 11 July, with Col. M A G Osmani as commander in chief, Lt. Col. Abdur Rab as chief of Army Staff and Group Captain A K Khandker as Deputy Chief of Army Staff and Chief of Air Force. Bangladesh was divided into Eleven Sectors each with a commander chosen from defected officers of Pakistan army who joined the Mukti Bahini to conduct guerrilla operations and train fighters. Most of their training camps were situated near the border area and were operated with assistance from India. The 10th Sector was directly placed under Commander in Chief (C-in-C) and included the Naval Commandos and C-in-C’s special force.[47] Three brigades (11 Battalions) were raised for conventional warfare; a large guerrilla force (estimated 100,000) was trained.

Guerrilla operations, which slackened during the training phase, picked up after August. Economic and military targets in Dhaka were attacked. The major success story was Operation Jackpot, in which naval commandos mined and blew up berthed ships in Chittagong on 16 August 1971. Pakistani reprisals claimed lives of thousands of civilians. The Indian army took over supplying the Mukti Bahini from the BSF. They organised six sectors for supplying the Bangladesh forces.

October – December[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Also See: Evolution of Pakistan Eastern Command plan, Bangladesh 1971: Opposing Plans, Pakistan Army Order of Battle December 1971 and Mitro Bahini Order of Battle December 1971

Bangladesh conventional forces attacked border outposts. Kamalpur, Belonia and Battle of Boyra are a few examples. 90 out of 370 BOPs fell to Bengali forces. Guerrilla attacks intensified, as did Pakistani and Razakar reprisals on civilian populations. Pakistani forces were reinforced by eight battalions from West Pakistan. The Bangladeshi independence fighters even managed to temporarily capture airstrips at Lalmonirhat and Shalutikar.[48] Both of these were used for flying in supplies and arms from India. Pakistan sent 5 battalions from West Pakistan as reinforcements.

Indian involvement[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

|

Major battles |

Wary of the growing involvement of India, the Pakistan Air Force (PAF) launched a pre-emptive strike on India. The attack was modelled on the Israeli Air Force's Operation Focus during the Six-Day War. However, the plan failed to achieve the desired success and was seen as an open act of unprovoked aggression against the Indians.

Indian prime minister Indira Gandhi declared war on Pakistan and in aid of the Mukti Bahini, then ordered the immediate mobilisation of troops and launched the full-scale invasion. This marked the official start of the Indo-Pakistani War.

Three Indian corps were involved in the invasion of East Pakistan. They were supported by nearly three brigades of Mukti Bahini fighting alongside them, and many more fighting irregularly. This was far superior to the Pakistani army of three divisions[49]. The Indians quickly overran the country, bypassing heavily defended strongholds. Pakistani forces were unable to effectively counter the Indian attack, as they had been deployed in small units around the border to counter guerrilla attacks by the Mukti Bahini.[50] Unable to defend Dhaka, the Pakistanis surrendered on 16 December 1971.

The speed of the Indian strategy can be gauged by the fact that one of the regiments of Indian army (7 Punjab now 8 Mechanised Inf Regiment) fought the liberation war along the Jessore and Khulna axis. They were newly converted to a mechanised regiment and it took them just 1 week to reach Khulna after capturing Jessore. Their losses were limited to just 2 newly acquired APCs (SKOT) from the Russians. thumb|Indian Army's T-55 tanks on their way to Dhaka. India's military intervention played a crucial role in turning the tide in favour of the Bangladeshi rebels. India's external intelligence agency, the RAW, played a crucial role in providing logistic support to the Mukti Bahini during the initial stages of the war. RAW's operations, in then-East Pakistan, was the largest covert operation in the history of South Asia.

Pakistani response[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Pakistan launched a number of armoured thrusts along India's western front in attempts to force Indian troops away from East Pakistan. Pakistan tried to fight back and boost the sagging morale by incorporating the Special Services Group commandos in sabotage and rescue missions.

[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

L'aviazione indiana mise a in atto diverse sortite contro il Pakistan e, nel giro di una settimana, ottenne il controllo dei cieli del Pakistan occidentale, tale supremazia fu ottenuta quando lo squadrone numero 14 delle forze aeree pakistane (PAF) fu distrutto dagli attacchi a Tejgaon, Kurmitolla, Lal Munir Hat e Shamsher Nagar. I Sea Hawk partiti dalla INS Vikrant colpirono Chittagong, Barisal e Cox's Bazar, distruggendo la branca orientale della flotta pakistana bloccando così i porti del Bengala tagliando le possibili vie di ritirata per i pakistani. La nascente flotta del Bangladesh (che comprendeva ufficiali e marinai che avevano disertato la marina pakistana) fornì supporto alle operazioni navali indiane, in particolar modo con l'Operazione Jackpot.

Surrender and aftermath[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

On 16 December 1971, Lt. Gen A. A. K. Niazi, CO of Pakistan Army forces located in East Pakistan signed the instrument of surrender. At the time of surrender only a few countries had provided diplomatic recognition to the new nation. Over 90,000 Pakistani troops surrendered to the Indian forces making it largest surrender since World War II. Bangladesh sought admission in the UN with most voting in its favor, but China vetoed this as Pakistan was its key ally.[51] The United States, also a key ally of Pakistan, was one of the last nations to accord Bangladesh recognition.[52] To ensure a smooth transition, in 1972 the Simla Agreement was signed between India and Pakistan. The treaty ensured that Pakistan recognized the independence of Bangladesh in exchange for the return of the Pakistani PoWs. India treated all the PoWs in strict accordance with the Geneva Convention, rule 1925[53]. It released more than 90,000 Pakistani PoWs in five months[54].

Further, as a gesture of goodwill, nearly 200 soldiers who were sought for war crimes by Bengalis were also pardoned by India. The accord also gave back more than 13,000 km² of land that Indian troops had seized in West Pakistan during the war, though India retained a few strategic areas;[55] most notably Kargil (which would in turn again be the focal point for a war between the two nations in 1999). This was done as a measure of promoting "lasting peace" and was acknowledged by many observers as a sign of maturity by India. But some in India felt that the treaty had been too lenient to Bhutto, who had pleaded for leniency, arguing that the fragile democracy in Pakistan would crumble if the accord was perceived as being overly harsh by Pakistanis.

Reaction in West Pakistan to the war[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Reaction to the defeat and dismemberment of half the nation was a shocking loss to top military and civilians alike. No one had expected that they would lose the formal war in under a fortnight and there was also anger at what was perceived as a meek surrender of the army in East Pakistan. Yahya Khan's dictatorship collapsed and gave way to Bhutto who took the opportunity to rise to power. General Niazi, who surrendered along with 93,000 troops, was viewed with suspicion and hatred upon his return to Pakistan. He was shunned and branded a traitor. The war also exposed the shortcoming of Pakistan's declared strategic doctrine that the "defence of East Pakistan lay in West Pakistan".[56] Pakistan also failed to gather international support, and were found fighting a lone battle with only the USA providing any external help. This further embittered the Pakistanis who had faced the worst military defeat of an army in decades.

The debacle immediately prompted an enquiry headed by Justice Hamdoor Rahman. Called the Hamoodur Rahman Commission, it was initially suppressed by Bhutto as it put the military in poor light. When it was declassified, it showed many failings from the strategic to the tactical levels. It also condemned the atrocities and the war crimes committed by the armed forces. It confirmed the looting, rapes and the killings by the Pakistan Army and their local agents although the figures are far lower than the ones quoted by Bangladesh. According to Bangladeshi sources, 200,000 women were raped and over 3 million people were killed, while the Rahman Commission report in Pakistan claimed 26,000 died and the rapes were in the hundreds. However, the army’s role in splintering Pakistan after its greatest military debacle was largely ignored by successive Pakistani governments.

Atrocities[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

During the war there were widespread killings and other atrocities – including the displacement of civilians in Bangladesh (East Pakistan at the time) and widespread violations of human rights – carried out by the Pakistan Army with support from political and religious militias began with the start of Operation Searchlight on 25 March 1971.

Bangladeshi authorities claim that three million people were killed,[7] while the Hamoodur Rahman Commission, an official Pakistan Government investigation, put the figure as low as 26,000 civilian casualties.[57] The international media and reference books in English have also published figures which vary greatly from 200,000 to 3,000,000 for Bangladesh as a whole.[7] A further eight to ten million people fled the country to seek safety in India.[58]

thumb|Rayerbazar killing field photographed immediately after the war, showing dead bodies of intellectuals (Image courtesy: Rashid Talukdar, 1971) A large section of the intellectual community of Bangladesh were murdered, mostly by the Al-Shams and Al-Badr forces,[59] at the instruction of the Pakistani Army.[60] Just 2 days before the surrender, on 14 December 1971, Pakistan Army and Razakar militia (local collaborators) picked up at least 100 physicians, professors, writers and engineers in Dhaka, and executed them, leaving the dead bodies in a mass grave.[61]. There are many mass graves in Bangladesh, and as years pass, more are being discovered (such as one in an old well near a mosque in Dhaka, located in the non-Bengali region of the city, which was discovered in August 1999).[62] The first night of war on Bengalis, which is documented in telegrams from the American Consulate in Dhaka to the United States State Department, saw indiscriminate killings of students of Dhaka University and other civilians.[63]

Numerous women were tortured, raped and killed during the war; the exact numbers are not known and are a subject of debate. Bangladeshi sources cite a figure of 200,000 women raped, giving birth to thousands of war babies. The Pakistan Army also kept numerous Bengali women as sex-slaves inside the Dhaka Cantonment. Most of the girls were captured from Dhaka University and private homes.[64]

There was significant sectarian violence not only perpetrated and encouraged by the Pakistani army,[65] but also by Bengali nationalists against non-Bengali minorities, especially Biharis.[66]

On 16 December 2002, the George Washington University's National Security Archive published a collection of declassified documents, consisting mostly of communications between US embassy officials and United States Information Service centers in Dhaka and India, and officials in Washington DC.[67] These documents show that US officials working in diplomatic institutions within Bangladesh used the terms selective genocide[68] and genocide (see The Blood Telegram) to describe events they had knowledge of at the time. Genocide is the term that is still used to describe the event in almost every major publication and newspaper in Bangladesh[69][70], although elsewhere, particularly in Pakistan, the actual death toll, motives, extent, and destructive impact of the actions of the Pakistani forces are disputed.

Foreign reaction[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

USA e URSS[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

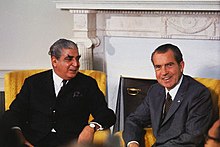

Gli Stati Uniti supportarono il Pakistan sia dal punto di vista politico che materiale. Il presidente Richard Nixon vietò ogni ingerenza nella questione affermando che si trattasse di affari interni al Pakistan. Tuavvia quando la sconfitta pakistana apparve certa Nixon inviò la portaerei USS Enterprise nella Baia del Bengala come minaccia atomica nei confronti dell'India The United States supported Pakistan both politically and materially. U.S. President Richard Nixon denied getting involved in the situation, saying that it was an internal matter of Pakistan. But when Pakistan's defeat seemed certain, Nixon sent the aircraft carrier USS Enterprise to the Bay of Bengal, a move deemed by the Indians as a nuclear threat. Enterprise arrived on station on 11 December 1971. On 6 December and 13 December, the Soviet Navy dispatched two groups of ships, armed with nuclear missiles, from Vladivostok; they trailed U.S. Task Force 74 in the Indian Ocean from 18 December until 7 January 1972.

Nixon and Henry Kissinger feared Soviet expansion into South and Southeast Asia. Pakistan was a close ally of the People's Republic of China, with whom Nixon had been negotiating a rapprochement and where he intended to visit in February 1972. Nixon feared that an Indian invasion of West Pakistan would mean total Soviet domination of the region, and that it would seriously undermine the global position of the United States and the regional position of America's new tacit ally, China. In order to demonstrate to China the bona fides of the United States as an ally, and in direct violation of the US Congress-imposed sanctions on Pakistan, Nixon sent military supplies to Pakistan and routed them through Jordan and Iran,[71] while also encouraging China to increase its arms supplies to Pakistan.

The Nixon administration also ignored reports it received of the genocidal activities of the Pakistani Army in East Pakistan, most notably the Blood telegram.

The Soviet Union supported Bangladesh and Indian armies, as well as the Mukti Bahini during the war, recognizing that the independence of Bangladesh would weaken the position of its rivals - the United States and China. It gave assurances to India that if a confrontation with the United States or China developed, the USSR would take counter-measures. This was enshrined in the Indo-Soviet friendship treaty signed in August 1971. The Soviets also sent a nuclear submarine to ward off the threat posed by USS Enterprise in the Indian Ocean.

Cina[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

In quanto alleato di lungo corso del Pakistan, la Repubblica Popolare Cinese reagì con preoccupazione all'evolversi della crisi nel Pakistan orientale ed alla prospettiva di un'invasione indiana del Bengala e della parte pakistana del Kashmir. Credendo che un attacco indiano fosse imminente Nixon incoraggiò una mobilitazione cinese sul confine indiano, al fine di scoraggiare tale eventualità. I cinesi tuttavia scelsero di esercitare pressioni per ottenere un immediato cessate il fuoco, tale comportamento fu dovuto alle pesanti perdite che i cinesi, pur vittoriosi, avevano sofferto nel corso della guerra Sino-Indianadel 1962. La Cina in ogni caso continuò a fornire forniture militari al Pakistan. Si crede che azioni militari cinesi contro l'India per proteggere il Pakistan Occidentale avrebbero causato azioni sovietiche contro la stessa Cina. Uno scrittore pakistano invece sostiene che la Cina non attaccò l'India solamente poiché i passi himalaiani erano bloccati, nei mesi di novembre e dicembre dalla neve.[72]

Nazioni Unite[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Malgrado la condanna delle Nazioni Unite per le violazioni dei diritti umani esse fallirono nel trovare una soluzione politica alla controversia prima dello scoppio della guerra. Il 4 dicembre il Consiglio di Sicurezza discusse della situazione del sud-est asiatico. L'URSS tuttavia oppose due volte il veto ad una risoluzione. Il 7 dicembre l'Assemblea Generale adottò a maggioranza una risoluzione che chiedeva l'"immediato cessate il fuoco ed il ritiro delle truppe". Gli Stati Uniti chiesero, il 12 dicembre, una nuova convocazione del Consiglio di Sicurezza, tuttavia la guerra finì prima che la convocazione si concretizzasse in una risoluzione ed in misure che non fossero meramente accademiche. La passività dell'ONU rispetto alla crisi nel Bengala fu ampiamente criticata, il conflitto inoltre dimostro la lentezza delle decisioni, che fu proprio la causa del fallimento di ogni azione risolutiva nei confronti del problema.

Nomenclature[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

This conflict is referred to by many different names, some of which carry political connotations:

"Bangladesh War" is a common name for this conflict, but this term is also used for the eastern front of the Indo-Pakistani War of 1971 war, and is generally understood to be coterminous with The Indo-Pakistani War of 1971 (see below).

"Bangladesh War of Independence" is the most commonly used name outside of the Indian subcontinent. It is a common name formally used to describe many other successful secessionist wars (see list of War of Independence).

"Bangladesh Liberation War" (Mukti Judhho in Bangla) is officially used in Bangladesh by all sources and by Indian official sources. The proponents claim that having won 167 out of 169 seats of East Pakistan, the Awami League had a popular mandate to form a democratic government, and this gave Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, as the leader of the party, the right to declare independence of the country. In Bangladeshi eyes, since Major Ziaur Rahman claimed independence on behalf of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, an independent Bangladeshi government was in existence as early as 26 March 1971, and therefore the war was fought by this government for the liberation of its territory.

This nomenclature is politically preferred by both India and Bangladesh for a few reasons:

- It gave India the right to enter the war in support of Bangladesh without breaching United Nations laws that prevent countries from interfering with other countries' internal affairs.

- Members of East Bengal Regiment were able to fight Pakistan Army without being treated as mutineers since they were fighting under command of a Bangladeshi Government.

- It eased Indian diplomatic efforts to gain support for the recognition of Bangladesh as a country.

"Pakistani Civil War" describes either the period of 26 March 1971 to 16 December 1971 or the period of 26 March 1971 to 3 December 1971. However, it is rejected by Bangladeshis who dislike the association with an internal struggle of the state of Pakistan.

"Indo-Pakistani War of 1971" is most commonly used to describe the period between 3 December 1971 and 16 December 1971. The Indian Army does not explicitly use the term to describe the war in their Eastern Front at any point. Instead, India only refers to the war on the Western Front as the Indo-Pakistani War. (Note that the Indian Parliament recognized the People's Republic of Bangladesh as an independent country on the 6 December 1971.)

See also[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

- Recipients of Bangladeshi military awards in 1971

- Artistic depictions of Bangladesh Liberation War

- Timeline of the Bangladesh War

- Mukti Bahini

- Liberation War Museum

Footnotes[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

- ^ http://articles.latimes.com/2002/mar/30/local/me-passings30.1

- ^ a b c India - Pakistan War, 1971; Introduction - Tom Cooper, Khan Syed Shaiz Ali

- ^ Pakistan & the Karakoram Highway By Owen Bennett-Jones, Lindsay Brown, John Mock, Sarina Singh, Pg 30</

- ^ p442 Indian Army after Independence by KC Pravel: Lancer 1987 [ISBN 81-7062-014-7]

- ^ a b Figures from The Fall of Dacca by Jagjit Singh Aurora in The Illustrated Weekly of India dated 23 December 1973 quoted in Indian Army after Independence by KC Pravel: Lancer 1987 [ISBN 81-7062-014-7]

- ^ Figure from Pakistani Prisioners of War in India by Col S.P. Salunke p.10 quoted in Indian Army after Independence by KC Pravel: Lancer 1987 (ISBN 81-7062-014-7)

- ^ a b c d Matthew White's Death Tolls for the Major Wars and Atrocities of the Twentieth Century Errore nelle note: Tag

<ref>non valido; il nome "MathewWhite" è stato definito più volte con contenuti diversi - ^ http://english.aljazeera.net/news/asia/2010/03/2010325151839747356.html

- ^ Genocide in Bangladesh, 1971. Gendercide Watch.

- ^ Emerging Discontent, 1966-70. Country Studies Bangladesh

- ^ Anatomy of Violence: Analysis of Civil War in East Pakistan in 1971: Military Action: Operation Searchlight Bose S Economic and Political Weekly Special Articles, 8 October 2005

- ^ The Pakistani Slaughter That Nixon Ignored , Syndicated Column by Sydney Schanberg, New York Times, 3 May 1994

- ^ a b Crisis in South Asia - A report by Senator Edward Kennedy to the Subcommittee investigating the Problem of Refugees and Their Settlement, Submitted to U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee, 1 November 1971, U.S. Govt. Press.pp6-7

- ^ India and Pakistan: Over the Edge. TIME 13 December 1971 Vol. 98 No. 24

- ^ Khalid B. Sayeed, The Political System of Pakistan, Houghton Mifflin, 1967, pp. 61.

- ^ a b Library of Congress studies

- ^ Demons of December — Road from East Pakistan to Bangladesh

- ^ Rounaq Jahan, Pakistan: Failure in National Integration, Columbia University Press, 1972, ISBN 0-231-03625-6. Pg 166-167

- ^ Al Helal, Bashir, Language Movement, Banglapedia

- ^ a b Language Movement (PHP), su Banglapedia - The National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. URL consultato il 6 febbraio 2007. Formato sconosciuto: PHP (aiuto)

- ^ International Mother Language Day - Background and Adoption of the Resolution, su Government of Bangladesh. URL consultato il 21 giugno 2007.

- ^ Tariq Rahman, Language and Ethnicity in Pakistan, in Asian Survey, vol. 37, n. 9, September 1997, pp. 833–839, DOI:10.1525/as.1997.37.9.01p02786, ISSN 0004-4687. URL consultato il 21 giugno 2007.

- ^ a b Tariq Rahman, The Medium of Instruction Controversy in Pakistan (PDF), in Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, vol. 18, n. 2, 1997, pp. 145–154, DOI:10.1080/01434639708666310, ISSN 0143-4632. URL consultato il 21 giugno 2007.

- ^ a b c Philip Oldenburg, "A Place Insufficiently Imagined": Language, Belief, and the Pakistan Crisis of 1971, in The Journal of Asian Studies, vol. 44, n. 4, August 1985, pp. 711–733, DOI:10.2307/2056443, ISSN 0021-9118. URL consultato il 21 giugno 2007.

- ^ India Meteorological Department, Annual Summary - Storms & Depressions (PDF), su India Weather Review 1970, 1970, pp. 10–11. URL consultato il 15 aprile 2007.

- ^ Kabir, M. M., Saha B. C.; Hye, J. M. A., Cyclonic Storm Surge Modelling for Design of Coastal Polder (PDF), su iwmbd.org, Institute of Water Modelling. URL consultato il 15 aprile 2007.

- ^ Sydney Schanberg, Yahya Condedes 'Slips' In Relief, in New York Times, 22 novembre 1970.

- ^ Staff writer, East Pakistani Leaders Assail Yahya on Cyclone Relief, in New York Times, Reuters, 23 novembre 1970.

- ^ Staff writer, Copter Shortage Balks Cyclone Aid, in New York Times, 18 novembre 1970.

- ^ Tillman Durdin, Pakistanis Crisis Virtually Halts Rehabilitation Work In Cyclone Region, in New York Times, 11 marzo 1971.

- ^ Richard Olson, A Critical Juncture Analysis, 1964-2003 (PDF), su usaid.gov, USAID, 21 febbraio 2005. URL consultato il 15 aprile 2007.

- ^ Sarmila Bose Anatomy of Violence: Analysis of Civil War in East Pakistan in 1971: Military Action: Operation Searchlight Economic and Political Weekly Special Articles, 8 October 2005

- ^ Salik, Siddiq, Witness To Surrender, p63, p228-9 id = ISBN 984-05-1373-7

- ^ From Deterrence and Coercive Diplomacy to War - The 1971 Crisis in South Asia. Asif Siddiqui, Journal of International and Area Studies Vol.4 No.1, 1997. 12. pp 73-92.

- ^ Virtual Bangladesh : History : The Bangali Genocide, 1971

- ^ Debasish Roy Chowdhury, 'Indians are bastards anyway', Asia Times, 23 giugno 2005.

- ^ Amita Malik, The Year of the Vulture, New Delhi, Orient Longmans, 1972, pp. 79–83, ISBN 0-8046-8817-6.

- ^ Encyclopedia Britannica - Agha Mohammad Yahya Khan

- ^ "Joy" is Bengali Word that means win

- ^ J. S. Gupta The History of the Liberation Movement in Bangladesh Page ??

- ^ The Daily Star, 26 March 2005 Article not specified

- ^ Virtual Bangladesh

- ^ Annex M (Oxford University Press, 2002 ISBN 0-19-579778-7)

- ^ India, Pakistan, and the United States: Breaking with the Past By Shirin R. Tahir-Kheli ISBN 0-87609-199-0, 1997, Council on Foreign Relations. pp 37

- ^ Pakistan Defence Journal, 1977, Vol 2, p2-3

- ^ http://www.state.gov/r/pa/ei/bgn/3452.htm

- ^ Bangladesh Liberation Armed Force, Liberation War Museum, Bangladesh.

- ^ India - Pakistan War, 1971; Introduction By Tom Cooper, with Khan Syed Shaiz Ali

- ^ Bangladesh: Out of War, a Nation Is Born

- ^ Indian Army after Independence by Maj KC Praval 1993 Lancer p317 ISBN 1-897829-45-0

- ^ Section 9. Situation in the Indian Subcontinent, 2. Bangladesh's international position - Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan

- ^ Guess who's coming to dinner Naeem Bangali

- ^ http://www.sacw.net/article524.html

- ^ 54 Indian PoWs of 1971 war still in Pakistan - Daily Times - Leading News Resource of Pakistan

- ^ The Simla Agreement 1972 - Story of Pakistan

- ^ Defencejournal, Redefining security imperatives by M Sharif - Article in Jang newspaper, General Niazi's Failure in High Command

- ^ Hamoodur Rahman Commission Report, chapter 2, paragraph 33

- ^ Rummel, Rudolph J., "Statistics of Democide: Genocide and Mass Murder Since 1900", ISBN 3-8258-4010-7, Chapter 8, Table 8.2 Pakistan Genocide in Bangladesh Estimates, Sources, and Calcualtions: lowest estimate two million claimed by Pakistan (reported by Aziz, Qutubuddin. Blood and tears Karachi: United Press of Pakistan, 1974. pp. 74,226), all the other sources used by Rummel suggest a figure of between 8 and 10 million with one (Johnson, B. L. C. Bangladesh. New York: Barnes & Noble, 1975. pp. 73,75) that "could have been" 12 million.

- ^ Many of the eyewitness accounts of relations that were picked up by "Al Badr" forces describe them as Bengali men. The only survivor of the Rayerbazar killings describes the captors and killers of Bengali professionals as fellow Bengalis. See 37 Dilawar Hossain, account reproduced in ‘Ekattorer Ghatok-dalalera ke Kothay’ (Muktijuddha Chetona Bikash Kendro, Dhaka, 1989)

- ^ Asadullah Khan The loss continues to haunt us in The Daily Star 14 December 2005

- ^ 125 Slain in Dacca Area, Believed Elite of Bengal, in New York Times, New York, NY, USA, 19 dicembre 1971, p. 1. URL consultato il 4 gennaio 2008.«At least 125 persons, believed to be physicians, professors, writers and teachers were found murdered today in a field outside Dacca. All the victims' hands were tied behind their backs and they had been bayoneted, garroted or shot. They were among an estimated 300 Bengali intellectuals who had been seized by West Pakistani soldiers and locally recruited supporters.»

- ^ DPA report Mass grave found in Bangladesh in The Chandigarh Tribune 8 August 1999

- ^ Sajit Gandhi The Tilt: The U.S. and the South Asian Crisis of 1971 National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book No. 79 16 December 2002

- ^ East Pakistan: Even the Skies Weep, Time Magazine, 25 October 1971.

- ^ U.S. Consulate (Dacca) Cable, Sitrep: Army Terror Campaign Continues in Dacca; Evidence Military Faces Some Difficulties Elsewhere, 31 March 1971, Confidential, 3 pp

- ^ Sumit Sen, Stateless Refugees and the Right to Return: the Bihari Refugees of South Asia, Part 1 (PDF), in International Journal of Refugee Law, vol. 11, n. 4, 1999, pp. 625–645, DOI:10.1093/ijrl/11.4.625. URL consultato il 20 ottobre 2006.

- ^ Gandhi, Sajit, ed. (16 December 2002), The Tilt: The U.S. and the South Asian Crisis of 1971: National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book No. 79

- ^ U.S. Consulate in Dacca (27 March 1971), Selective genocide, Cable (PDF)

- ^ Editorial "The Jamaat Talks Back" in The Bangladesh Observer 30 December 2005

- ^ Dr. N. Rabbee "Remembering a Martyr" Star weekend Magazine, The Daily Star 16 December 2005

- ^ Shalom, Stephen R., The Men Behind Yahya in the Indo-Pak War of 1971

- ^ The Pakistan Army From 1965 to 1971 Analysis and reappraisal after the 1965 War by Maj (Retd) Agha Humayun Amin

References[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

- Pierre Stephen and Robert Payne: Massacre, Macmillan, New York, (1973). ISBN 0-02-595240-4

- Christopher Hitchens “The Trials of Henry Kissinger”, Verso (2001). ISBN 1-85984-631-9

- Library of Congress Country Studies

Further reading[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

- Ayoob, Mohammed and Subrahmanyam, K., The Liberation War, S. Chand and Co. pvt Ltd. New Delhi, 1972.

- Bhargava, G.S., Crush India or Pakistan's Death Wish, ISSD, New Delhi, 1972.

- Bhattacharyya, S. K., Genocide in East Pakistan/Bangladesh: A Horror Story, A. Ghosh Publishers, 1988.

- Brownmiller, Susan: Against Our Will: Men, Women, and Rape, Ballantine Books, 1993.

- Choudhury, G.W., "Bangladesh: Why It Happened." International Affairs. (1973). 48(2): 242-249.

- Choudhury, G.W., The Last Days of United Pakistan, Oxford University Press, 1994.

- Govt. of Bangladesh, Documents of the war of Independence, Vol 01-16, Ministry of Information.

- Kanjilal, Kalidas, The Perishing Humanity, Sahitya Loke, Calcutta, 1976

- Johnson, Rob, 'A Region in Turmoil' (New York and London, 2005)

- Malik, Amita, The Year of the Vulture, Orient Longmans, New Delhi, 1972.

- Mascarenhas, Anthony, The Rape of Bangla Desh, Vikas Publications, 1972.

- Matinuddin, General Kamal, Tragedy of Errors: East Pakistan Crisis, 1968–1971, Wajidalis, Lahore, Pakistan, 1994.

- Mookherjee, Nayanika, A Lot of History: Sexual Violence, Public Memories and the Bangladesh Liberation War of 1971, D. Phil thesis in Social Anthropology, SOAS, University of London, 2002.

- National Security Archive, The Tilt: the U.S. and the South Asian Crisis of 1971

- Quereshi, Major General Hakeem Arshad, The 1971 Indo-Pak War, A Soldiers Narrative, Oxford University Press, 2002.

- Rummel, R.J., Death By Government, Transaction Publishers, 1997.

- Salik, Siddiq, Witness to Surrender, Oxford University Press, Karachi, Pakistan, 1977.

- Sisson, Richard & Rose, Leo, War and secession: Pakistan, India, and the creation of Bangladesh, University of California Press (Berkeley), 1990.

- Totten, Samuel et al., eds., Century of Genocide: Eyewitness Accounts and Critical Views, Garland Reference Library, 1997

- US Department of State Office of the Historian, Foreign Relations of the United States: Nixon-Ford Administrations, vol. E-7, Documents on South Asia 1969–1972

- Zaheer, Hasan: The separation of East Pakistan: The rise and realization of Bengali Muslim nationalism, Oxford University Press, 1994.

Collegamenti esterni[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

- Banglapedia article on the Liberation war of Bangladesh

- 1971 Bangladesh Genocide Archive

- Video Streaming of 5 Liberation war documentaries

- Video, audio footage, news reports, pictures and resources from Mukto-mona

- Picture Gallery of the Language Movement 1952 & the Independence War 1971 of Bangladesh

- Bangladesh Liberation War. Mujibnagar. Government Documents 1971

- Torture in Bangladesh 1971–2004 (PDF)

- Eyewitness Accounts: Genocide in Bangladesh

- Genocide 1971

- The women of 1971. Tales of abuse and rape by the Pakistan Army.

- Mathematics of a Massacre, Abul Kashem

- The complete Hamoodur Rahman Commission Report

- 1971 Massacre in Bangladesh and the Fallacy in the Hamoodur Rahman Commission Report, Dr. M.A. Hasan

- Women of Pakistan Apologize for War Crimes, 1996

- Pakistan Army not involved

- Sheikh Mujib wanted a confederation: US papers, by Anwar Iqbal, Dawn, 7 July 2005

- Page containing copies of the surrender documents

- A website dedicated to Liberation war of Bangladesh

- Video clip of the surrender by Pakistan

- Bangladesh Liberation War Picture Gallery Graphic images, viewer discretion advised