Utente:Brunokito/Sandbox71

| II emendamento della Costituzione degli Stati Uniti d'America | |

|---|---|

| |

| Stato | |

| Tipo legge | Legge costituzionale |

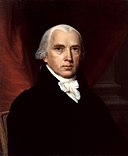

| Proponente | James Madison, e la Common law inglese Influenzato dalla Carta dei diritti del 1689 |

| Promulgazione | 15 dicembre 1791 |

| In vigore | 27 giugno 2008 |

| Testo | |

| (EN) II Emendamento, in The Bill of Rights: A Transcription, National Archives. URL consultato il 21 gennaio 2023. | |

Il II emendamento della Costituzione degli Stati Uniti d'America (Emendamento II) tutela il diritto di detenere e portare armi negli Stati Uniti. Fu ratificato il 15 dicembre 1791, insieme ad altri nove articoli della Carta dei diritti.[1][2][3] Nella sentenza District of Columbia v. Heller (2008),[4] la Corte Suprema ha affermato per la prima volta che il diritto appartiene agli individui, per l'autodifesa in casa,[5][6][7][8] pur includendo, come dicta, che il diritto non è illimitato e non preclude l'esistenza di alcuni divieti di lunga data, come quelli che vietano “il possesso di armi da fuoco da parte di criminali e malati mentali” o le restrizioni sul “porto di armi pericolose e insolite”.[9][10] Nella causa McDonald v. City of Chicago (2010)[11] la Corte Suprema ha stabilito che i governi statali e locali sono limitati nella stessa misura del governo federale dal violare questo diritto.[12][13] New York State Rifle & Pistol Association, Inc. v. Bruen (2022)[14] ha assicurato il diritto di portare armi negli spazi pubblici con ragionevoli eccezioni.

Il Secondo Emendamento si basa in parte sul diritto di tenere e portare armi nella common law inglese ed è stato influenzato dalla Carta dei diritti inglese del 1689. Sir William Blackstone descrisse questo diritto come un diritto ausiliario, a sostegno dei diritti naturali di autodifesa e resistenza all'oppressione, e del dovere civico di agire di concerto in difesa dello Stato.[15] Sebbene sia James Monroe che John Adams fossero favorevoli alla ratifica della Costituzione, il suo più influente ideatore fu James Madison. Ne Il Federalista n. 46, Madison scrisse come un esercito federale potesse essere tenuto sotto controllo dalla milizia, “un esercito permanente... sarebbe contrastato [dalla] milizia”. Egli sostenne che i governi statali “sarebbero stati in grado di respingere il pericolo” di un esercito federale: “Si può ben dubitare che una milizia così circostanziata possa mai essere conquistata da una tale proporzione di truppe regolari”. Egli contrappose il governo federale degli Stati Uniti ai regni europei, che descrisse come “timorosi di affidare al popolo le armi”, e assicurò che “l'esistenza di governi subordinati... forma una barriera contro le imprese dell'ambizione”.[16][17]

Nel gennaio 1788, Delaware, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Georgia e Connecticut ratificarono la Costituzione senza insistere sugli emendamenti. Diversi emendamenti furono proposti, ma non furono adottati al momento della ratifica della Costituzione. Ad esempio, la convenzione della Pennsylvania discusse quindici emendamenti, uno dei quali riguardava il diritto del popolo ad essere armato, un altro la milizia. Anche la convenzione del Massachusetts ratificò la Costituzione con un elenco allegato di emendamenti proposti. Alla fine, la convenzione di ratifica era così equamente divisa tra favorevoli e contrari alla Costituzione che i federalisti accettarono la Carta dei diritti per assicurare la ratifica. Nella causa United States v. Cruikshank (1876),[18] la Corte Suprema stabilì che “il diritto di portare armi non è concesso dalla Costituzione, né dipende in alcun modo da tale strumento per la sua esistenza”. Il Secondo Emendamento non significa altro che non deve essere violato dal Congresso e non ha altro effetto che quello di limitare i poteri del Governo nazionale”.[19] Nella causa United States v. Miller[20] (1939), la Corte Suprema ha stabilito che il Secondo Emendamento non protegge i tipi di armi che non hanno una “ragionevole relazione con la conservazione o l'efficienza di una milizia ben regolamentata”.[21][22]

Nel XXI secolo, l'emendamento è stato oggetto di una nuova indagine accademica e di un rinnovato interesse giudiziario.[22][23] Nella causa District of Columbia v. Heller (2008),[24] la Corte Suprema ha emesso una decisione storica che ha stabilito che l'emendamento protegge il diritto di un individuo di tenere un'arma per la difesa personale.[25][26] È stata la prima volta che la Corte ha stabilito che il Secondo Emendamento garantisce il diritto individuale di possedere un'arma.[27][28][26] Nella causa McDonald v. Chicago (2010),[29] la Corte Suprema ha chiarito che la clausola del giusto processo del XIV emendamento incorpora il Secondo Emendamento contro i governi statali e locali.[30] In Caetano v. Massachusetts (2016),[31] la Corte Suprema ha ribadito le sue precedenti sentenze che “il Secondo Emendamento si estende, prima facie, a tutti gli strumenti che costituiscono armi portabili, anche a quelli che non esistevano al momento della fondazione” e che la sua protezione non è limitata “solo alle armi utili in guerra”. Oltre ad affermare il diritto di portare armi da fuoco in pubblico, la sentenza NYSRPA v. Bruen (2022)[32] ha creato un nuovo principio in base al quale le leggi che cercano di limitare i diritti del Secondo Emendamento devono basarsi sulla storia e sulla tradizione dei diritti delle armi da fuoco, sebbene il principio sia stato perfezionato per concentrarsi su analoghe analogie e principi generali piuttosto che su rigide corrispondenze con il passato nella sentenza United States v. Rahimi (2024).[33] Il dibattito tra varie organizzazioni sul controllo delle armi e sui diritti delle armi continua.[34]

Testo

[modifica | modifica wikitesto]Esistono diverse versioni del testo del Secondo Emendamento, ciascuna con differenze di capitalizzazione o punteggiatura. Esistono differenze tra la versione approvata dal Congresso e messa in mostra e le versioni ratificate dagli Stati.[35][36][37][38] Queste differenze sono state al centro di dibattiti sul significato dell'emendamento, in particolare sull'importanza di quella che i tribunali hanno definito la clausola prefatoria.[39][40]

L'originale finale, scritto a mano, della Carta dei diritti come approvata dal Congresso, con il resto dell'originale preparato dallo scriba William Lambert, è conservato negli Archivi Nazionali.[41] Si tratta della versione ratificata dal Delaware[42] e utilizzata dalla Corte Suprema nella causa District of Columbia v. Heller:[43]

«Una milizia ben regolamentata, essendo necessaria alla sicurezza di uno Stato libero, non può essere violato il diritto del popolo di tenere e portare armi.»

Alcune versioni ratificate dallo Stato, come quella del Maryland, hanno omesso la prima o l'ultima virgola:[42][44][36]

Gli atti di ratifica di New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island e Carolina del Sud contenevano una sola virgola, ma con differenze nella capitalizzazione. L'atto della Pennsylvania afferma:[45][46][47]

«Essendo necessaria una milizia ben regolata per la sicurezza di uno Stato libero, il diritto del popolo di tenere e portare armi non sarà violato.»

L'atto di ratifica del New Jersey non contiene virgole:[42]

«Essendo necessaria una milizia ben regolata per la sicurezza di uno Stato libero il diritto del popolo di tenere e portare armi non sarà violato.»

Contesto precostituzionale

[modifica | modifica wikitesto]Influenza della Carta dei diritti inglese del 1689

[modifica | modifica wikitesto]Il diritto dei protestanti di portare armi in Storia dell'Inghilterra è considerato nella common law inglese come un diritto ausiliario subordinato ai diritti primari di sicurezza personale, libertà personale e proprietà privata. Secondo Sir William Blackstone, “l'ultimo... diritto ausiliario del suddito... è quello di avere armi per la propria difesa, adatte alla sua condizione e al suo grado, e quelle consentite dalla legge. Il che è ... dichiarato da ... uno statuto, ed è in effetti una concessione pubblica, con le dovute restrizioni, del diritto naturale di resistenza e di autoconservazione, quando le sanzioni della società e delle leggi si rivelino insufficienti a frenare la violenza dell'oppressione".[48]

La Carta dei diritti del 1689 è emersa da un periodo tempestoso della politica inglese, durante il quale due questioni sono state le principali fonti di conflitto: l'autorità del re di governare senza il consenso del Parlamento e il ruolo dei cattolici in un Paese a maggioranza protestante. Alla fine, il cattolico Giacomo II fu rovesciato nella Gloriosa Rivoluzione e i suoi successori, i protestanti Guglielmo III e Maria II, accettarono le condizioni codificate nella legge. Una delle questioni risolte dal disegno di legge era l'autorità del re di disarmare i suoi sudditi, dopo che Giacomo II aveva disarmato molti protestanti “sospettati o conosciuti” di non gradire il governo[49] e aveva discusso con il Parlamento sul suo desiderio di mantenere un esercito permanente.[N 1] Il disegno di legge afferma di agire per ripristinare "antichi diritti" calpestati da Giacomo II, anche se alcuni hanno sostenuto che la Carta dei diritti inglese aveva creato un nuovo diritto ad avere armi, che si sviluppò da un dovere di avere armi.[50] Nella causa District of Columbia v. Heller (2008),[51] la Corte Suprema non accettò questo punto di vista, osservando che il diritto inglese all'epoca dell'approvazione della Carta dei diritti era "chiaramente un diritto individuale, che non aveva nulla a che fare con il servizio nella milizia" e che si trattava di un diritto a non essere disarmati dalla Corona e non era la concessione di un nuovo diritto ad avere armi.[52]

Il testo della Carta dei diritti inglese del 1689 include un linguaggio che protegge il diritto dei protestanti dal disarmo da parte della Corona, affermando che: “Che i sudditi che sono protestanti possano avere armi per la loro difesa adatte alle loro condizioni e come consentito dalla legge”.[53] Conteneva anche un testo che aspirava a vincolare i futuri Parlamenti, anche se secondo il diritto costituzionale inglese nessun Parlamento può vincolare un Parlamento successivo.[54]

L'affermazione della Carta dei diritti inglese relativa al diritto di portare armi è spesso citata solo nel passaggio in cui è scritta come sopra e non nel suo contesto completo, dove è chiaro che la Carta dei diritti affermava il diritto dei cittadini protestanti a non essere disarmati dal re senza il consenso del Parlamento e si limitava a ripristinare i diritti dei protestanti che il precedente re aveva brevemente e illegalmente rimosso. Nel suo contesto completo si legge:[53]

«Considerando che il defunto Re Giacomo Secondo, con l'aiuto di diversi cattivi Consiglieri, Giudici e Ministri da lui impiegati, tentò di sovvertire ed estirpare la Religione Protestante e le Leggi e le Libertà di questo Regno (elenco delle rimostranze incluse) ... facendo sì che diversi buoni sudditi, che erano Protestanti, venissero disarmati nello stesso momento in cui i Papisti erano armati e impiegati in modo contrario alla Legge, (Considerazione riguardante il cambio di monarca) . ... quindi i suddetti Signori Spirituali e Temporali e i Comuni, in base alle loro rispettive lettere ed elezioni, essendo ora riuniti in piena e libera rappresentanza di questa Nazione, prendendo in seria considerazione i mezzi migliori per raggiungere i fini sopra menzionati, dichiarano in primo luogo, come hanno fatto di solito i loro antenati in casi simili, di rivendicare e affermare i loro antichi diritti e libertà, (elenco dei diritti inclusi) ... Che i sudditi che sono protestanti possano avere armi per la loro difesa adeguate alle loro condizioni e come consentito dalla legge.»

La Corte Suprema degli Stati Uniti ha riconosciuto il legame storico tra la Carta dei diritti inglese e il Secondo Emendamento, che codificano entrambi un diritto esistente e non ne creano uno nuovo.[N 2][N 3]

La Carta dei diritti inglese include la clausola che le armi devono essere “consentite dalla legge”. Questo è stato il caso prima e dopo l'approvazione del decreto. Sebbene non abbia annullato le precedenti restrizioni sul possesso di armi per la caccia, è soggetto al diritto parlamentare di abrogare implicitamente o esplicitamente le leggi precedenti.[56]

Vi è una certa divergenza di opinioni su quanto siano stati effettivamente rivoluzionari gli eventi del 1688-89 e diversi commentatori sottolineano che le disposizioni della Carta dei diritti inglese non rappresentavano nuove leggi, ma piuttosto affermavano diritti esistenti. Mark Thompson ha scritto che, a parte la determinazione della successione, la Carta dei diritti inglese non fece “molto di più che enunciare alcuni punti delle leggi esistenti e semplicemente assicurare agli inglesi i diritti di cui erano già in possesso”.[57] Prima e dopo la Carta dei diritti inglese, il governo poteva sempre disarmare qualsiasi individuo o classe di individui che considerava pericolosi per la pace del regno.[58] Nel 1765, Sir William Blackstone scrisse i Commentaries on the Laws of England (Commentari sulle leggi d'Inghilterra),[59] descrivendo il diritto di possedere armi in Inghilterra durante il XVIII secolo come un diritto ausiliario subordinato del suddito, “dichiarato anche” nella Carta dei diritti inglese.[48][60][61][62]

«Il quinto e ultimo diritto ausiliario del suddito, che ora menzionerò, è quello di avere armi per la propria difesa, adatte alla propria condizione e al proprio grado, e quelle consentite dalla legge. Questo è anche dichiarato dallo stesso statuto 1 W. & M. st.2. c.2. ed è in effetti una concessione pubblica, con le dovute restrizioni, del diritto naturale di resistenza e autoconservazione, quando le sanzioni della società e delle leggi si rivelano insufficienti a frenare la violenza dell'oppressione.»

Sebbene ci siano pochi dubbi sul fatto che gli autori del Secondo Emendamento siano stati fortemente influenzati dalla Carta dei diritti inglese, è una questione di interpretazione se essi intendessero preservare il potere di regolamentare le armi agli Stati rispetto al governo federale, come il Parlamento inglese aveva riservato a se stesso contro il monarca, o se intendessero creare un nuovo diritto simile a quello di altri scritto nella Costituzione, come la Corte Suprema ha deciso nella sentenza Heller. Alcuni negli Stati Uniti hanno preferito l'argomento dei “diritti”, sostenendo che la Carta dei diritti inglese aveva concesso un diritto. La necessità di avere armi per l'autodifesa non era in realtà oggetto di controversia. I popoli di tutto il mondo, da sempre, si sono armati per proteggere se stessi e gli altri e, con la nascita delle nazioni organizzate, questi accordi sono stati estesi alla protezione dello Stato.[N 4][64]

Influenza della legge inglese sulla milizia del 1757

[modifica | modifica wikitesto]In 1757 Parlamento del Regno Unito created "An Act for better ordering of the militia forces in the several counties of that part of Great Britain called England".[65] This act declared that "a well-ordered and well-disciplined militia is essentially necessary to the safety, peace and prosperity of this kingdom," and that the current militia laws for the regulation of the militia were defective and ineffectual. Influenced by this act, in 1775 Timothy Pickering created "An Easy Plan of Discipline for a Militia".[66] Greatly inhibited by the events surrounding Salem, Massachusetts, where the plan was printed, Pickering submitted the writing to George Washington.[67] On May 1, 1776, the Massachusetts Bay Councell resolved that Pickering's discipline, a modification of the 1757 act, be the discipline of their Militia.[68] On marzo 29, 1779, for members of the Continental Army this was replaced by Von Steuben's Regulations for the Order and Discipline of the Troops of the United States.[69] With ratification of the Second Amendment, after May 8, 1792, the entire United States Militia, barring two declarations, would be regulated by Von Steuben's Discipline.[70]

L'America prima della Costituzione degli Stati Uniti

[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Il re Carlo I d'Inghilterra autorizzò l'uso delle armi per la difesa speciale e la sicurezza, in terra e in mare, contro:

The Military Company of Massachusetts had already ordered munition before the authorization was signed. Early Americans had other uses for arms, besides the uses King Charles had in mind:[N 5][N 6][73][74][75][76][77][78]

- safeguarding against tyrannical governments[79]

- suppressing insurrection, allegedly including rivolte degli schiavi,[80][81][82] though professor Paul Finkelman has pointed out that the claim of a specific intent to protect the ability to put down slave revolts is not supported by the historical record[83]

- facilitating a natural right of self-defense[84]

Which of these considerations were thought of as most important and ultimately found expression in the Second Amendment is disputed. Some of these purposes were explicitly mentioned in early state constitutions; for example, the Costituzione della Pennsylvania del 1776 asserted that, "the people have a right to bear arms for the defence of themselves and the state."[85]

During the 1760s pre-revolutionary period, the established colonial militia was composed of colonists, including many who were loyal to British rule. As defiance and opposition to British rule developed, a distrust of these Loyalists in the militia became widespread among the colonists known as Patriots, who favored independence from British rule. As a result, some Patriots created their own militias that excluded the Loyalists and then sought to stock independent armories for their militias. In response to this arms build-up, the British Parliament established an embargo of firearms, parts and ammunition against the American colonies[86] which in some instance came to be referred to as Powder Alarms. King George III also began disarming individuals who were in the most rebellious areas in the 1760s and 1770s.[87]

British and Loyalist efforts to disarm the colonial Patriot militia armories in the early phases of the Rivoluzione americana resulted in the Patriot colonists protesting by citing the Dichiarazione dei diritti del 1689, Blackstone's summary of the Declaration of Right, their own militia laws and diritti di autodifesa secondo la common law.[88] While British policy in the early phases of the Revolution clearly aimed to prevent coordinated action by the Patriot militia, some have argued that there is no evidence that the British sought to restrict the traditional common law right of self-defense.[88] Patrick J. Charles disputes these claims citing similar disarming by the patriots and challenging those scholars' interpretation of Blackstone.[89]

The right of the colonists to arms and rebellion against oppression was asserted, for example, in a pre-revolutionary newspaper editorial in 1769 objecting to the Crown suppression of colonial opposition to the Townshend Acts:[88][90]

«Instances of the licentious and outrageous behavior of the military conservators of the peace still multiply upon us, some of which are of such nature, and have been carried to such lengths, as must serve fully to evince that a late vote of this town, calling upon its inhabitants to provide themselves with arms for their defense, was a measure as prudent as it was legal: such violences are always to be apprehended from military troops, when quartered in the body of a populous city; but more especially so, when they are led to believe that they are become necessary to awe a spirit of rebellion, injuriously said to be existing therein. It is a natural right which the people have reserved to themselves, confirmed by the Bill of Rights, to keep arms for their own defence; and as Mr. Blackstone observes, it is to be made use of when the sanctions of society and law are found insufficient to restrain the violence of oppression.»

The armed forces that won the American Revolution consisted of the standing Continental Army created by the Continental Congress, together with esercito e forze navali regolari francesi and various state and regional militia units. In opposition, the British forces consisted of a mixture of the standing British Army, Loyalist militia and mercenari Assiani. Following the Revolution, the United States was governed by the Articles of Confederation. Federalists argued that this government had an unworkable division of power between Congress and the states, which caused military weakness, as the esercito permanente was reduced to as few as 80 men.[91] They considered it to be bad that there was no effective federal military crackdown on an armed tax rebellion in western Massachusetts known as Ribellione di Shays.[92] Anti-federalists, on the other hand, took the side of limited government and sympathized with the rebels, many of whom were former Revolutionary War soldiers. Subsequently, the Constitutional Convention proposed in 1787 to grant Congress exclusive power to raise and support a standing army and navy of unlimited size.[93][94] Antifederalisti objected to the shift of power from the states to the federal government, but as adoption of the Constitution became more and more likely, they shifted their strategy to establishing a bill of rights that would put some limits on federal power.[95]

Modern scholars Thomas B. McAffee and Michael J. Quinlan have stated that James Madison "did not invent the right to keep and bear arms when he drafted the Second Amendment; the right was pre-existing at both common law and in the early state constitutions."[96] In contrast, historian Jack Rakove suggests that Madison's intention in framing the Second Amendment was to provide assurances to moderate Anti-Federalists that the militias would not be disarmed.[97]

One aspect of the gun control debate is the conflict between gun control laws and the right to rebel against unjust governments. Blackstone in his Commentaries alluded to this right to rebel as the natural right of resistance and self preservation, to be used only as a last resort, exercisable when "the sanctions of society and laws are found insufficient to restrain the violence of oppression".[48] Some believe that the framers of the Bill of Rights sought to balance not just political power, but also military power, between the people, the states and the nation,[98] as Alexander Hamilton explained in his "Riguardo alla milizia" essay published in 1788:[98][99]

«... it will be possible to have an excellent body of well-trained militia, ready to take the field whenever the defence of the State shall require it. This will not only lessen the call for military establishments, but if circumstances should at any time oblige the Government to form an army of any magnitude, that army can never be formidable to the liberties of the People, while there is a large body of citizens, little, if at all, inferior to them in discipline and the use of arms, who stand ready to defend their own rights, and those of their fellow-citizens. This appears to me the only substitute that can be devised for a standing army, and the best possible security against it, if it should exist.»

There was an ongoing debate beginning in 1789 about "the people" fighting governmental tyranny (as described by Anti-Federalists); or the risk of mob rule of "the people" (as described by the Federalists) related to the increasingly violent French Revolution.[100] A widespread fear, during the debates on ratifying the Constitution, was the possibility of a military takeover of the states by the federal government, which could happen if the Congress passed laws prohibiting states from arming citizens,[N 7] or prohibiting citizens from arming themselves.[88] Though it has been argued that the states lost the power to arm their citizens when the power to arm the militia was transferred from the states to the federal government by Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution, the individual right to arm was retained and strengthened by the Leggi sulla milizia del 1792 and the similar act of 1795.[101][102]

More recently some have advanced what has been called the teoria insurrezionalista of the Second Amendment whereby it is the right of any citizen to take up arms against their government should they consider it illegitimate. Such a reading has been voiced by organizations such as the National Rifle Association of America (NRA)[103] and by various individuals including some elected officials.[104] Congressman Jamie Raskin, however, has argued that there is no basis in constitutional law or scholarship for this view.[105] He notes that, not only does this represent a misreading of the text of the Amendment as drafted, it stands in violation of other elements of the Constitution.[105]

Precursori della Costituzione statale del Secondo Emendamento

[modifica | modifica wikitesto]| Articoli e sezioni correlati delle prime Costituzioni statali che furono adottate dopo il 10 maggio 1776.

Nota: il 10 maggio 1776, il Congresso approvò una risoluzione che raccomandava a tutte le colonie con un governo non incline all'indipendenza di formarne uno che lo fosse.[106] |

Virginia, 12 giugno 1776[modifica | modifica wikitesto]La Costituzione della Virginia elenca le ragioni che hanno portato allo scioglimento dei legami con il Re e alla formazione di un proprio governo statale indipendente. Tra cui le seguenti:

Una dichiarazione dei diritti. Sezione 13. Che una milizia ben regolata, composta dal corpo del popolo, addestrato alle armi, è la difesa appropriata, naturale e sicura di uno Stato libero; che gli eserciti permanenti, in tempo di pace, dovrebbero essere evitati, in quanto pericolosi per la libertà; e che in tutti i casi l'esercito dovrebbe essere sotto stretta sorveglianza e governo del potere civile.[107] |

Pennsylvania, 28 settembre 1776[modifica | modifica wikitesto]Articolo 13. Che il popolo ha il diritto di portare le armi per difendere se stesso e lo Stato; e che, poiché gli eserciti permanenti in tempo di pace sono pericolosi per la libertà, non dovrebbero essere mantenuti; e che le forze armate dovrebbero essere tenute sotto stretta subordinazione e governate dal potere civile.[108] Questo è il primo caso, in relazione al diritto costituzionale degli Stati Uniti, dell'espressione “diritto di portare armi”. Articolo 43. Gli abitanti di questo Stato avranno la libertà di pescare e cacciare nei periodi stagionali sulle terre che possiedono, e su tutte le altre terre che non sono recintate;[109] È importante notare che la Pennsylvania era una colonia quacchera tradizionalmente contraria al porto d'armi. "Nell'istituire la Pennsylvania, William Penn aveva in mente un grande esperimento, un "sacro esperimento", come lo definì. Si trattava nientemeno che di testare, su una scala di considerevole grandezza, la praticabilità di fondare e governare uno Stato sui principi sicuri della religione cristiana; dove l'esecutivo doveva essere sostenuto senza armi; dove la giustizia doveva essere amministrata senza giuramenti; e dove la vera religione poteva fiorire senza l'incubo di un sistema gerarchico”.[110] I residenti non quaccheri, molti dei quali provenienti dalle contee occidentali, si lamentavano spesso e a gran voce di vedersi negato il diritto a una difesa comune. All'epoca della Rivoluzione Americana, attraverso quella che potrebbe essere descritta come una rivoluzione nella rivoluzione, le fazioni pro-milizia avevano conquistato l'ascendente nel governo dello Stato. E grazie a una manipolazione attraverso l'uso di giuramenti, che squalificavano i membri quaccheri, costituirono una vasta maggioranza della convenzione per la formazione della nuova costituzione statale; era naturale che affermassero i loro sforzi per formare una milizia statale obbligatoria nel contesto di un “diritto” a difendere se stessi e lo Stato.[111] |

Maryland, 11 novembre 1776[modifica | modifica wikitesto]Articoli XXV-XXVII. 25. Che una milizia ben regolata è la giusta e naturale difesa di un governo libero. 26. Che gli eserciti permanenti sono pericolosi per la libertà e non dovrebbero essere creati o mantenuti senza il consenso del legislatore. 27. Che in ogni caso e in ogni momento l'esercito deve essere strettamente subordinato e controllato dal potere civile.[112] |

Carolina del Nord, 18 dicembre 1776[modifica | modifica wikitesto]Una dichiarazione dei diritti. Articolo XVII. Che il popolo ha il diritto di portare le armi per la difesa dello Stato; e che, poiché gli eserciti permanenti, in tempo di pace, sono pericolosi per la libertà, non dovrebbero essere mantenuti; e che l'esercito dovrebbe essere tenuto sotto stretta subordinazione e governato dal potere civile.[113] |

New York, 20 aprilee 1777[modifica | modifica wikitesto]Articolo XL. E considerando che per la sicurezza di ogni Stato è della massima importanza che esso sia sempre in condizione di difendersi, e che è dovere di ogni uomo che gode della protezione della società essere preparato e disposto a difenderla; questa convenzione, pertanto, in nome e per l'autorità del buon popolo di questo Stato, ordina, stabilisce e dichiara che la milizia di questo Stato, in ogni momento successivo, sia in pace che in guerra, sarà armata e disciplinata, e pronta al servizio. Che tutti gli abitanti di questo Stato, appartenenti al popolo chiamato quacchero, che per scrupoli di coscienza sono contrari al porto d'armi, siano esonerati dal legislatore e paghino allo Stato, in sostituzione del loro servizio personale, le somme di denaro che, a giudizio del legislatore, possono valere. E che un'adeguata riserva di armi da guerra, proporzionata al numero di abitanti, sia, per sempre, a spese dello Stato e con atti del legislatore, stabilita, mantenuta e continuata in ogni contea di questo Stato.[114] |

Vermont, 8 luglio 1777[modifica | modifica wikitesto]Capitolo 1. Sezione XVIII. Che il popolo ha il diritto di portare le armi per la difesa di se stesso e dello Stato; e che gli eserciti permanenti, in tempo di pace, sono pericolosi per la libertà e non dovrebbero essere mantenuti; e che l'esercito dovrebbe essere tenuto sotto stretta subordinazione e governato dal potere civile.[115] |

Massachusetts, 15 giugno 1780[modifica | modifica wikitesto]Una dichiarazione dei diritti. Capitolo 1. Articolo XVII. Il popolo ha il diritto di tenere e portare armi per la difesa comune. E poiché, in tempo di pace, gli eserciti sono pericolosi per la libertà, non devono essere mantenuti senza il consenso del legislatore; e il potere militare deve sempre essere tenuto in esatta subordinazione all'autorità civile ed essere governato da essa.[116] |

Stesura e adozione della Costituzione

[modifica | modifica wikitesto]In marzo 1785, delegates from Virginia and Maryland assembled at the Mount Vernon Conference to fashion a remedy to the inefficiencies of the Articles of Confederation. The following year, alla Convenzione di Annapolis in Maryland, 12 delegates from five states (New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Delaware, and Virginia) met and drew up a list of problems with the current government model. At its conclusion, the delegates scheduled a follow-up meeting in Filadelfia, Pennsylvania for May 1787 to present solutions to these problems, such as the absence of:[120][121]

- interstate arbitration processes to handle quarrels between states;

- sufficiently trained and armed intrastate security forces to suppress insurrection;

- a national militia to repel foreign invaders.

It quickly became apparent that the solution to all three of these problems required shifting control of the states' militias to the federal Congress and giving it the power to raise a standing army.[122] Article 1, Section 8[123] of the Constitution codified these changes by allowing the Congress to provide for the common defense and general welfare of the United States by doing the following:[124]

- raise and support armies, but no appropriation of money to that use shall be for a longer term than two years;

- provide and maintain a navy;

- make rules for the government and regulation of the land and naval forces;

- provide for calling forth the militia to execute the laws of the union, suppress insurrections and repel invasions;

- provide for organizing, arming, and disciplining the militia, and for governing such part of them as may be employed in the service of the United States, reserving to the states respectively, the appointment of the officers, and the authority of training the militia according to the discipline prescribed by Congress.

Some representatives mistrusted proposals to enlarge federal powers, because they were concerned about the inherent risks of centralizing power. Federalists, including James Madison, initially argued that a bill of rights was unnecessary, sufficiently confident that the federal government could never raise a standing army powerful enough to overcome a militia.[125] Federalist Noah Webster argued that an armed populace would have no trouble resisting the potential threat to liberty of a standing army.[126][127] Antifederalisti, on the other hand, advocated amending the Constitution with clearly defined and enumerated rights providing more explicit constraints on the new government. Many Anti-federalists feared the new federal government would choose to disarm state militias. Federalists countered that in listing only certain rights, unlisted rights might lose protection. The Federalists realized there was insufficient support to ratify the Constitution without a bill of rights and so they promised to support amending the Constitution to add a bill of rights following the Constitution's adoption. This compromise persuaded enough Anti-federalists to vote for the Constitution, allowing for ratification.[128] The Constitution was declared ratified on giugno 21, 1788, when nine of the original thirteen states had ratified it. The remaining four states later followed suit, although the last two states, North Carolina and Rhode Island, ratified only after Congress had passed the Bill of Rights and sent it to the states for ratification.[129] James Madison drafted what ultimately became the Bill of Rights, which was proposed by the first Congress on giugno 8, 1789, and was adopted on dicembre 15, 1791.

Dibattiti sull'emendamento della Costituzione

[modifica | modifica wikitesto]The debate surrounding the Constitution's ratification is of practical importance, particularly to adherents of originalisti and costruzionisti rigorosi legal theories. In the context of such legal theories and elsewhere, it is important to understand the language of the Constitution in terms of what that language meant to the people who wrote and ratified the Constitution.[130]

Robert Whitehill, a delegate from Pennsylvania, sought to clarify the draft Constitution with a bill of rights explicitly granting individuals the right to hunt on their own land in season,[131] though Whitehill's language was never debated.[132]

Argomentazione a favore del potere statale

[modifica | modifica wikitesto]There was substantial opposition to the new Constitution because it moved the power to arm the state militias from the states to the federal government. This created a fear that the federal government, by neglecting the upkeep of the militia, could have overwhelming military force at its disposal through its power to maintain a standing army and navy, leading to a confrontation with the states, encroaching on the states' reserved powers and even engaging in a military takeover. Article VI of the Articles of Confederation states:[133][134]

«In tempo di pace nessuno Stato potrà tenere in servizio navi da guerra, se non nel numero ritenuto necessario dagli Stati Uniti, riuniti in congresso, per la difesa dello Stato stesso o del suo commercio; e nessuno Stato potrà tenere in servizio forze in tempo di pace, se non nel numero ritenuto necessario, a giudizio degli Stati Uniti, riuniti in congresso, per presidiare i forti necessari alla difesa dello Stato stesso; ma ogni Stato dovrà sempre mantenere una milizia ben regolata e disciplinata, sufficientemente armata e equipaggiata, e dovrà fornire e tenere costantemente pronti all'uso, nei magazzini pubblici, un numero adeguato di pezzi da campo e di tende, e una quantità adeguata di armi, munizioni e attrezzature da campo.»

In contrast, Article I, Section 8, Clause 16 of the U.S. Constitution states:[135]

«Per provvedere all'organizzazione, all'armamento e alla disciplina della Milizia e per governare la parte di essa che può essere impiegata al servizio degli Stati Uniti, riservando agli Stati rispettivamente la nomina degli ufficiali e l'autorità di addestrare la Milizia secondo la disciplina prescritta dal Congresso.»

La tirannia del governo

[modifica | modifica wikitesto]A foundation of American political thought during the Revolutionary period was concern about political corruption and governmental tyranny. Even the federalists, fending off their opponents who accused them of creating an oppressive regime, were careful to acknowledge the risks of tyranny. Against that backdrop, the framers saw the personal right to bear arms as a potential check against tyranny. Theodore Sedgwick of Massachusetts expressed this sentiment by declaring that it is "a chimerical idea to suppose that a country like this could ever be enslaved ... Is it possible ... that an army could be raised for the purpose of enslaving themselves or their brethren? Or, if raised whether they could subdue a nation of freemen, who know how to prize liberty and who have arms in their hands?"[136] Noah Webster similarly argued:[16][137]

«Prima che un esercito permanente possa governare, il popolo deve essere disarmato, come avviene in quasi tutti i regni d'Europa. Il potere supremo in America non può imporre leggi ingiuste con la spada, perché l'intero corpo del popolo è armato e costituisce una forza superiore a qualsiasi banda di truppe regolari che possa essere, con qualsiasi pretesa, sollevata negli Stati Uniti.»

George Mason also argued the importance of the militia and right to bear arms by reminding his compatriots of the British government's efforts "to disarm the people; that it was the best and most effectual way to enslave them ... by totally disusing and neglecting the militia." He also clarified that under prevailing practice the militia included all people, rich and poor. "Who are the militia? They consist now of the whole people, except a few public officers." Because all were members of the militia, all enjoyed the right to individually bear arms to serve therein.[16][138]

Writing after the ratification of the Constitution, but before the election of the first Congress, James Monroe included "the right to keep and bear arms" in a list of basic "human rights", which he proposed to be added to the Constitution.[139]

Patrick Henry argued in the Virginia ratification convention on giugno 5, 1788, for the dual rights to arms and resistance to oppression:[140]

«Custodite con gelosa attenzione la libertà pubblica. Sospettate di chiunque si avvicini a quel gioiello. Purtroppo, nulla la preserverà se non la forza. Ogni volta che si rinuncia a questa forza, si è inevitabilmente rovinati.»

Mantenimento della schiavitù

[modifica | modifica wikitesto]Conservazione delle pattuglie di schiavi

[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

In the slave states, the militia was available for military operations, but its biggest function was to police the slaves.[141][142] According to Dr Carl T. Bogus, Professor of Law of the Roger Williams University Law School in Rhode Island,[141] the Second Amendment was written to assure the Southern states that Congress would not undermine the slave system by using its newly acquired constitutional authority over the militia to disarm the state militia and thereby destroy the South's principal instrument of slave control.[143] In his close analysis of James Madison's writings, Bogus describes the South's obsession with militias during the ratification process:[143]

«La milizia rimase il mezzo principale per proteggere l'ordine sociale e preservare il controllo dei bianchi su un'enorme popolazione nera. Qualsiasi cosa potesse indebolire questo sistema rappresentava la più grave delle minacce.»

This preoccupation is clearly expressed in 1788[143] by the slaveholder Patrick Henry:[141]

«Se il Paese viene invaso, uno Stato può entrare in guerra, ma non può reprimere le insurrezioni [secondo questa nuova Costituzione]. Se dovesse verificarsi un'insurrezione di schiavi, non si può dire che il Paese sia invaso. Non possono, quindi, reprimerla senza l'interposizione del Congresso... Il Congresso, e solo il Congresso [secondo la nuova Costituzione; aggiunta non menzionata nella fonte], può richiamare la milizia.»

Therefore, Bogus argues, in a compromise with the slave states, and to reassure Patrick Henry, George Mason and other slaveholders that they would be able to keep their slave control militias independent of the federal government, James Madison (also slave owner) redrafted the Second Amendment into its current form "for the specific purpose of assuring the Southern states, and particularly his constituents in Virginia, that the federal government would not undermine their security against slave insurrection by disarming the militia."[143]

Legal historian Paul Finkelman argues that this scenario is implausible.[83] Henry and Mason were political enemies of Madison's, and neither man was in Congress at the time Madison drafted Bill of Rights; moreover, Patrick Henry argued against the ratification of both the Constitution and the Second Amendment, and it was Henry's opposition that led Patrick's home state of Virginia to be the last to ratify.[83]

Most Southern white men between the ages of 18 and 45 were required to serve on "pattuglie di schiavi" which were organized groups of white men who enforced discipline upon enslaved blacks.[144] Bogus writes with respect to Georgia laws passed in 1755 and 1757 in this context: "The Georgia statutes required patrols, under the direction of commissioned militia officers, to examine every plantation each month and authorized them to search 'all Negro Houses for offensive Weapons and Ammunition' and to apprehend and give twenty lashes to any slave found outside plantation grounds."[145][146]

Finkelman recognises that James Madison "drafted an amendment to protect the right of the states to maintain their militias," but insists that "The amendment had nothing to do with state police powers, which were the basis of slave patrols."[83]

Per evitare di armare i neri liberi

[modifica | modifica wikitesto]Firstly, slave owners feared that enslaved blacks might be emancipated through military service. A few years earlier, there had been a precedent when Lord Dunmore offered freedom to slaves who escaped and joined his forces with "Liberty to Slaves" stitched onto their jacket pocket flaps.[147] Freed slaves also served in General Washington's army.

Secondly, they also greatly feared "a ruinous slave rebellion in which their families would be slaughtered and their property destroyed." When Virginia ratified the Bill of Rights on dicembre 15, 1791, the Haitian Revolution, a successful slave rebellion, was under way. The right to bear arms was therefore deliberately tied to membership in a militia by the slaveholder and chief drafter of the Amendment, James Madison, because only whites could join militias in the South.[148]

In 1776, Thomas Jefferson had submitted a draft constitution for Virginia that said "no freeman shall ever be debarred the use of arms within his own lands or tenements". According to Picadio, this version was rejected because "it would have given to free blacks the constitutional right to have firearms".[149]

Il conflitto e il compromesso al Congresso producono la Carta dei diritti.

[modifica | modifica wikitesto]James Madison's initial proposal for a bill of rights was brought to the floor of the House of Representatives on giugno 8, 1789, during the first session of Congress. The initial proposed passage relating to arms was:[150]

«Il diritto del popolo di tenere e portare armi non sarà violato; una milizia ben armata e ben regolamentata è la migliore sicurezza di un Paese libero; ma nessuna persona religiosamente scrupolosa di portare armi sarà costretta a prestare servizio militare di persona.»

On luglio 21, Madison again raised the issue of his bill and proposed that a select committee be created to report on it. The House voted in favor of Madison's motion,[151] and the Bill of Rights entered committee for review. The committee returned to the House a reworded version of the Second Amendment on luglio 28.[152] On agosto 17, that version was read into the Journal:[153]

«Una milizia ben regolata, composta dal corpo del popolo, essendo la migliore sicurezza di uno Stato libero, il diritto del popolo di tenere e portare armi non sarà violato; ma nessuna persona con scrupoli religiosi sarà obbligata a portare armi.»

In late agosto 1789, the House debated and modified the Second Amendment. These debates revolved primarily around the risk of "mal-administration of the government" using the "religiously scrupulous" clause to destroy the militia as British forces had attempted to destroy the Patriot militia at the commencement of the American Revolution. These concerns were addressed by modifying the final clause, and on agosto 24, the House sent the following version to the Senate:

«Una milizia ben regolata, composta dal corpo del popolo, essendo la migliore sicurezza di uno Stato libero, il diritto del popolo di tenere e portare armi non sarà violato; ma nessuno che abbia lo scrupolo religioso di portare armi sarà obbligato a prestare servizio militare di persona.»

The next day, agosto 25, the Senate received the amendment from the House and entered it into the Senate Journal. However, the Senate scribe added a comma before "shall not be infringed" and changed the semicolon separating that phrase from the religious exemption portion to a comma:[154]

«Una milizia ben regolata, composta dal corpo del popolo, la migliore sicurezza di uno Stato libero, il diritto del popolo di tenere e portare armi non sarà violato, ma nessuno che abbia lo scrupolo religioso di portare armi sarà obbligato a prestare servizio militare di persona.»

By this time, the proposed right to keep and bear arms was in a separate amendment, instead of being in a single amendment together with other proposed rights such as the due process right. As a representative explained, this change allowed each amendment to "be passed upon distinctly by the States".[155] On settembre 4, the Senate voted to change the language of the Second Amendment by removing the definition of militia, and striking the conscientious objector clause:[156]

«Una milizia ben regolamentata, essendo la migliore sicurezza di uno Stato libero, il diritto del popolo di tenere e portare armi non deve essere violato.»

The Senate returned to this amendment for a final time on settembre 9. A proposal to insert the words "for the common defence" next to the words "bear arms" was defeated. A motion passed to replace the words "the best", and insert in lieu thereof "necessary to the" .[157] The Senate then slightly modified the language to read as the fourth article and voted to return the Bill of Rights to the House. The final version by the Senate was amended to read as:

«Essendo necessaria una milizia ben regolata per la sicurezza di uno Stato libero, il diritto del popolo di tenere e portare armi non sarà violato.»

The House voted on settembre 21, 1789, to accept the changes made by the Senate.

The enrolled original Joint Resolution passed by Congress on settembre 25, 1789, on permanent display in the Rotunda, reads as:[158]

«A well regulated militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the People to keep and bear arms, shall not be infringed.»

On dicembre 15, 1791, the Bill of Rights (the first ten amendments to the Constitution) was adopted, having been ratified by three-fourths of the states, having been ratified as a group by all the fourteen states then in existence except Connecticut, Massachusetts, and Georgia – which added ratifications in 1939.[159]

La milizia dopo la ratifica

[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

During the first two decades following the ratification of the Second Amendment, public opposition to standing armies, among Anti-Federalists and Federalists alike, persisted and manifested itself locally as a general reluctance to create a professional armed police force, instead relying on county sheriffs, constables and night watchmen to enforce local ordinances.[86] Though sometimes compensated, often these positions were unpaid – held as a matter of civic duty. In these early decades, law enforcement officers were rarely armed with firearms, using sfollagente as their sole defensive weapons.[86] In serious emergencies, a posse comitatus, militia company, or group of vigilanti assumed law enforcement duties; these individuals were more likely than the local sheriff to be armed with firearms.[86]

On May 8, 1792, Congress passed "[a]n act more effectually to provide for the National Defence, by establishing an Uniform Militia throughout the United States" requiring:[160]

«[E]ach and every free able-bodied white male citizen of the respective States, resident therein, who is or shall be of age of eighteen years, and under the age of forty-five years (except as is herein after excepted) shall severally and respectively be enrolled in the militia ... [and] every citizen so enrolled and notified, shall, within six months thereafter, provide himself with a good musket or firelock, a sufficient bayonet and belt, two spare flints, and a knapsack, a pouch with a box therein to contain not less than twenty-four cartridges, suited to the bore of his musket or firelock, each cartridge to contain a proper quantity of powder and ball: or with a good rifle, knapsack, shot-pouch and powder-horn, twenty balls suited to the bore of his rifle, and a quarter of a pound of powder; and shall appear, so armed, accoutred and provided, when called out to exercise, or into service, except, that when called out on company days to exercise only, he may appear without a knapsack.»

The act also gave specific instructions to domestic weapon manufacturers "that from and after five years from the passing of this act, muskets for arming the militia as herein required, shall be of bores sufficient for balls of the eighteenth part of a pound."[160] In practice, private acquisition and maintenance of rifles and muskets meeting specifications and readily available for militia duty proved problematic; estimates of compliance ranged from 10 to 65 percent.[161] Compliance with the enrollment provisions was also poor. In addition to the exemptions granted by the law for custom-house officers and their clerks, post-officers and stage drivers employed in the care and conveyance of U.S. mail, ferrymen, export inspectors, pilots, merchant mariners and those deployed at sea in active service; state legislatures granted numerous exemptions under Section 2 of the Act, including exemptions for: clergy, conscientious objectors, teachers, students, and jurors. Though a number of able-bodied white men remained available for service, many simply did not show up for militia duty. Penalties for failure to appear were enforced sporadically and selectively.[162] None is mentioned in the legislation.[160]

The first test of the militia system occurred in luglio 1794, when a group of disaffected Pennsylvania farmers rebelled against federal tax collectors whom they viewed as illegitimate tools of tyrannical power.[163] Attempts by the four adjoining states to raise a militia for nationalization to suppress the insurrection proved inadequate. When officials resorted to drafting men, they faced bitter resistance. Forthcoming soldiers consisted primarily of draftees or paid substitutes as well as poor enlistees lured by enlistment bonuses. The officers, however, were of a higher quality, responding out of a sense of civic duty and patriotism, and generally critical of the rank and file.[86] Most of the 13,000 soldiers lacked the required weaponry; the war department provided nearly two-thirds of them with guns.[86] In ottobre, President George Washington and General Harry Lee marzoed on the 7,000 rebels who conceded without fighting. The episode provoked criticism of the citizen militia and inspired calls for a universal militia. Secretary of War Henry Knox and Vice President John Adams had lobbied Congress to establish federal armories to stock imported weapons and encourage domestic production.[86] Congress did subsequently pass "[a]n act for the erecting and repairing of Arsenals and Magazines" on aprile 2, 1794, two months prior to the insurrection.[164] Nevertheless, the militia continued to deteriorate and twenty years later, the militia's poor condition contributed to several losses in the War of 1812, including the sacking of Washington, D.C., and the burning of the White House in 1814.[162]

In the 20th century, Congress passed the Militia Act of 1903. The act defined the militia as every able-bodied male aged 18 to 44 who was a citizen or intended to become one. The militia was then divided by the act into the United States National Guard and the unorganized Reserve Militia.[165][166]

Federal law continues to define the militia as all able-bodied males aged 17 to 44, who are citizens or intend to become one, and female citizens who are members of the National Guard. The militia is divided into the organized militia, which consists of the National Guard and Naval Militia, and the unorganized militia.[167]

Commenti degli studiosi

[modifica | modifica wikitesto]Commenti iniziali

[modifica | modifica wikitesto]L'"agricoltore federale”

[modifica | modifica wikitesto]In May 1788, the pseudonymous author "Federal Farmer" (his real identity is presumed to be either Richard Henry Lee or Melancton Smith) wrote in Additional Letters From The Federal Farmer #169 or Letter XVIII regarding the definition of a "militia":

«A militia, when properly formed, are in fact the people themselves, and render regular troops in a great measure unnecessary.»

George Mason

[modifica | modifica wikitesto]In giugno 1788, George Mason addressed the Virginia Ratifying Convention regarding a "militia:"

«A worthy member has asked, who are the militia, if they be not the people, of this country, and if we are not to be protected from the fate of the Germans, Prussians, &c. by our representation? I ask who are the militia? They consist now of the whole people, except a few public officers. But I cannot say who will be the militia of the future day. If that paper on the table gets no alteration, the militia of the future day may not consist of all classes, high and low, and rich and poor; but may be confined to the lower and middle classes of the people, granting exclusion to the higher classes of the people. If we should ever see that day, the most ignominious punishments and heavy fines may be expected. Under the present government all ranks of people are subject to militia duty.»

Tench Coxe

[modifica | modifica wikitesto]In 1792, Tench Coxe made the following point in a commentary on the Second Amendment:[168][169][170]

«As civil rulers, not having their duty to the people duly before them, may attempt to tyrannize, and as the military forces which must be occasionally raised to defend our country, might pervert their power to the injury of their fellow citizens, the people are confirmed by the next article in their right to keep and bear their private arms.»

Tucker/Blackstone

[modifica | modifica wikitesto]The earliest published commentary on the Second Amendment by a major constitutional theorist was by St. George Tucker. He annotated a five-volume edition of Sir William Blackstone's Commentaries on the Laws of England, a critical legal reference for early American attorneys published in 1803.[171][172] Tucker wrote:[173]

«A well regulated militia being necessary to the security of a free state, the right of the people to keep, and bear arms, shall not be infringed. Amendments to C. U. S. Art. 4. This may be considered as the true palladium of liberty ... The right of self defence is the first law of nature: In most governments it has been the study of rulers to confine this right within the narrowest limits possible. Wherever standing armies are kept up, and the right of the people to keep and bear arms is, under any colour or pretext whatsoever, prohibited, liberty, if not already annihilated, is on the brink of destruction. In England, the people have been disarmed, generally, under the specious pretext of preserving the game : a never failing lure to bring over the landed aristocracy to support any measure, under that mask, though calculated for very different purposes. True it is, their bill of rights seems at first view to counteract this policy: but the right of bearing arms is confined to protestants, and the words suitable to their condition and degree, have been interpreted to authorise the prohibition of keeping a gun or other engine for the destruction of game, to any farmer, or inferior tradesman, or other person not qualified to kill game. So that not one man in five hundred can keep a gun in his house without being subject to a penalty.»

In footnotes 40 and 41 of the Commentaries, Tucker stated that the right to bear arms under the Second Amendment was not subject to the restrictions that were part of English law: "The right of the people to keep and bear arms shall not be infringed. Amendments to C. U. S. Art. 4, and this without any qualification as to their condition or degree, as is the case in the British government" and "whoever examines the forest, and game laws in the British code, will readily perceive that the right of keeping arms is effectually taken away from the people of England." Blackstone himself also commented on English game laws, Vol. II, p. 412, "that the prevention of popular insurrections and resistance to government by disarming the bulk of the people, is a reason oftener meant than avowed by the makers of the forest and game laws."[171] Blackstone discussed the right of self-defense in a separate section of his treatise on the common law of crimes. Tucker's annotations for that latter section did not mention the Second Amendment but cited the standard works of English jurists such as Hawkins.[N 8]

Further, Tucker criticized the English Bill of Rights for limiting gun ownership to the very wealthy, leaving the populace effectively disarmed, and expressed the hope that Americans "never cease to regard the right of keeping and bearing arms as the surest pledge of their liberty."[171]

William Rawle

[modifica | modifica wikitesto]Tucker's commentary was soon followed, in 1825, by that of William Rawle in his landmark text A View of the Constitution of the United States of America. Like Tucker, Rawle condemned England's "arbitrary code for the preservation of game", portraying that country as one that "boasts so much of its freedom", yet provides a right to "protestant subjects only" that it "cautiously describ[es] to be that of bearing arms for their defence" and reserves for "[a] very small proportion of the people[.]"[174] In contrast, Rawle characterizes the second clause of the Second Amendment, which he calls the corollary clause, as a general prohibition against such capricious abuse of government power.

Speaking of the Second Amendment generally, Rawle wrote:[175][176][177]

«The prohibition is general. No clause in the Constitution could by any rule of construction be conceived to give to congress a power to disarm the people. Such a flagitious attempt could only be made under some general pretence by a state legislature. But if in any blind pursuit of inordinate power, either should attempt it, this amendment may be appealed to as a restraint on both.»

Rawle, long before the concept of incorporation was formally recognized by the courts, or Congress drafted the Fourteenth Amendment, contended that citizens could appeal to the Second Amendment should either the state or federal government attempt to disarm them. He did warn, however, that "this right [to bear arms] ought not ... be abused to the disturbance of the public peace" and, paraphrasing Coke, observed: "An assemblage of persons with arms, for unlawful purpose, is an indictable offence, and even the carrying of arms abroad by a single individual, attended with circumstances giving just reason to fear that he purposes to make an unlawful use of them, would be sufficient cause to require him to give surety of the peace."[174]

Joseph Story

[modifica | modifica wikitesto]Joseph Story articulated in his influential Commentaries on the Constitution[178] the orthodox view of the Second Amendment, which he viewed as the amendment's clear meaning:[179][180]

«The right of the citizens to keep and bear arms has justly been considered, as the palladium of the liberties of a republic; since it offers a strong moral check against the usurpations and arbitrary power of rulers; and it will generally, even if these are successful in the first instance, enable the people to resist and triumph over them. And yet, though this truth would seem so clear, and the importance of a well-regulated militia would seem so undeniable, it cannot be disguised, that among the American people there is a growing indifference to any system of militia discipline, and a strong disposition, from a sense of its burdens, to be rid of all regulations. How it is practicable to keep the people duly armed without some organization, it is difficult to see. There is certainly no small danger, that indifference may lead to disgust, and disgust to contempt; and thus gradually undermine all the protection intended by this clause of our National Bill of Rights.»

Story describes a militia as the "natural defence of a free country", both against foreign foes, domestic revolts and usurpation by rulers. The book regards the militia as a "moral check" against both usurpation and the arbitrary use of power, while expressing distress at the growing indifference of the American people to maintaining such an organized militia, which could lead to the undermining of the protection of the Second Amendment.[180]

Lysander Spooner

[modifica | modifica wikitesto]L'Abolitionista Lysander Spooner, commenting on bills of rights, stated that the object of all bills of rights is to assert the rights of individuals against the government and that the Second Amendment right to keep and bear arms was in support of the right to resist government oppression, as the only security against the tyranny of government lies in forcible resistance to injustice, for injustice will certainly be executed, unless forcibly resisted.[181] Spooner's theory provided the intellectual foundation for John Brown and other radical abolitionists who believed that arming slaves was not only morally justified, but entirely consistent with the Second Amendment.[182] An express connection between this right and the Second Amendment was drawn by Lysander Spooner who commented that a "right of resistance" is protected by both the right to trial by jury and the Second Amendment.[183]

The congressional debate on the proposed Fourteenth Amendment concentrated on what the Southern States were doing to harm the newly freed slaves, including disarming the former slaves.[184]

Timothy Farrar

[modifica | modifica wikitesto]In 1867, Judge Timothy Farrar published his Manual of the Constitution of the United States of America, which was written when the Fourteenth Amendment was "in the process of adoption by the State legislatures":[170][185]

«The States are recognized as governments, and, when their own constitutions permit, may do as they please; provided they do not interfere with the Constitution and laws of the United States, or with the civil or natural rights of the people recognized thereby, and held in conformity to them. The right of every person to "life, liberty, and property", to "keep and bear arms", to the "writ of habeas corpus" to "trial by jury", and divers others, are recognized by, and held under, the Constitution of the United States, and cannot be infringed by individuals or even by the government itself.»

Il giudice Thomas Cooley

[modifica | modifica wikitesto]Judge Thomas M. Cooley, perhaps the most widely read constitutional scholar of the nineteenth century, wrote extensively about this amendment,[186][187] and he explained in 1880 how the Second Amendment protected the "right of the people":[188]

«It might be supposed from the phraseology of this provision that the right to keep and bear arms was only guaranteed to the militia; but this would be an interpretation not warranted by the intent. The militia, as has been elsewhere explained, consists of those persons who, under the law, are liable to the performance of military duty, and are officered and enrolled for service when called upon. But the law may make provision for the enrolment of all who are fit to perform military duty, or of a small number only, or it may wholly omit to make any provision at all; and if the right were limited to those enrolled, the purpose of this guaranty might be defeated altogether by the action or neglect to act of the government it was meant to hold in check. The meaning of the provision undoubtedly is, that the people, from whom the militia must be taken, shall have the right to keep and bear arms; and they need no permission or regulation of law for the purpose. But this enables the government to have a well-regulated militia; for to bear arms implies something more than the mere keeping; it implies the learning to handle and use them in a way that makes those who keep them ready for their efficient use; in other words, it implies the right to meet for voluntary discipline in arms, observing in doing so the laws of public order.»

Commento dalla fine del XX secolo

[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Until the late 20th century, there was little scholarly commentary of the Second Amendment.[189] In the latter half of the 20th century, there was considerable debate over whether the Second Amendment protected an individual right or a collective right.[190] The debate centered on whether the prefatory clause ("A well regulated militia being necessary to the security of a free State") declared the amendment's only purpose or merely announced a purpose to introduce the operative clause ("the right of the People to keep and bear arms shall not be infringed"). Scholars advanced three competing theoretical models for how the prefatory clause should be interpreted.[191]

The first, known as the "states' rights" or "collective right" model, held that the Second Amendment does not apply to individuals; rather, it recognizes the right of each state to arm its militia. Under this approach, citizens "have no right to keep or bear arms, but the states have a collective right to have the National Guard".[170] Advocates of collective rights models argued that the Second Amendment was written to prevent the federal government from disarming state militias, rather than to secure an individual right to possess firearms.[192] Prior to 2001, every circuit court decision that interpreted the Second Amendment endorsed the "collective right" model.[193][194] However, beginning with the Fifth Circuit's opinion United States v. Emerson in 2001, some circuit courts recognized that the Second Amendment protects an individual right to bear arms.[195][196]

The second, known as the "sophisticated collective right model", held that the Second Amendment recognizes some limited individual right. However, this individual right could be exercised only by actively participating members of a functioning, organized state militia.[197][192] Some scholars have argued that the "sophisticated collective rights model" is, in fact, the functional equivalent of the "collective rights model".[198] Other commentators have observed that prior to Emerson, five circuit courts specifically endorsed the "sophisticated collective right model".[199]

The third, known as the "standard model", held that the Second Amendment recognized the personal right of individuals to keep and bear arms.[170] Supporters of this model argued that "although the first clause may describe a general purpose for the amendment, the second clause is controlling and therefore the amendment confers an individual right 'of the people' to keep and bear arms".[200] Additionally, scholars who favored this model argued the "absence of founding-era militias mentioned in the Amendment's preamble does not render it a 'dead letter' because the preamble is a 'philosophical declaration' safeguarding militias and is but one of multiple 'civic purposes' for which the Amendment was enacted".[201]

Under both of the collective right models, the opening phrase was considered essential as a pre-condition for the main clause.[202] These interpretations held that this was a grammar structure that was common during that era[203] and that this grammar dictated that the Second Amendment protected a collective right to firearms to the extent necessary for militia duty.[204] However, under the standard model, the opening phrase was believed to be prefatory or amplifying to the operative clause. The opening phrase was meant as a non-exclusive example – one of many reasons for the amendment.[60] This interpretation is consistent with the position that the Second Amendment protects a modified individual right.[205]

The question of a collective right versus an individual right was progressively resolved in favor of the individual rights model, beginning with the Fifth Circuit ruling in United States v. Emerson (2001),[206] along with the Supreme Court's rulings in District of Columbia v. Heller (2008),[207] and McDonald v. Chicago (2010).[208] In Heller, the Supreme Court resolved any remaining circuit splits by ruling that the Second Amendment protects an individual right.[209] Although the Second Amendment is the only Constitutional amendment with a prefatory clause, such linguistic constructions were widely used elsewhere in the late eighteenth century.[210]

Warren E. Burger, a conservative Republican appointed chief justice of the United States by President Richard Nixon, wrote in 1990 following his retirement:[211]

«The Constitution of the United States, in its Second Amendment, guarantees a "right of the people to keep and bear arms". However, the meaning of this clause cannot be understood except by looking to the purpose, the setting and the objectives of the draftsmen ... People of that day were apprehensive about the new "monster" national government presented to them, and this helps explain the language and purpose of the Second Amendment ... We see that the need for a state militia was the predicate of the "right" guaranteed; in short, it was declared "necessary" in order to have a state military force to protect the security of the state.»

And in 1991, Burger stated:[212]

«If I were writing the Bill of Rights now, there wouldn't be any such thing as the Second Amendment ... that a well regulated militia being necessary for the defense of the state, the peoples' rights to bear arms. This has been the subject of one of the greatest pieces of fraud – I repeat the word 'fraud' – on the American public by special interest groups that I have ever seen in my lifetime.»

In a 1992 opinion piece, six former American attorneys general wrote:[213]

«For more than 200 years, the federal courts have unanimously determined that the Second Amendment concerns only the arming of the people in service to an organized state militia; it does not guarantee immediate access to guns for private purposes. The nation can no longer afford to let the gun lobby's distortion of the Constitution cripple every reasonable attempt to implement an effective national policy toward guns and crime.»

Research by Robert Spitzer found that every law journal article discussing the Second Amendment through 1959 "reflected the Second Amendment affects citizens only in connection with citizen service in a government organized and regulated militia." Only beginning in 1960 did law journal articles begin to advocate an "individualist" view of gun ownership rights.[214][215] The opposite of this "individualist" view of gun ownership rights is the "collective-right" theory, according to which the amendment protects a collective right of states to maintain militias or an individual right to keep and bear arms in connection with service in a militia (for this view see for example the citazione of Justice John Paul Stevens in the Meaning of "well regulated militia" section below).[216] In his book, Six Amendments: How and Why We Should Change the Constitution, Justice John Paul Stevens for example submits the following revised Second Amendment: "A well regulated militia, being necessary to the security of a free state, the right of the people to keep and bear arms when serving in the militia shall not be infringed."[217]

Significato di “milizia ben regolamentata”

[modifica | modifica wikitesto]An early use of the phrase "well-regulated militia" may be found in Andrew Fletcher's 1698 A Discourse of Government with Relation to Militias, as well as the phrase "ordinary and ill-regulated militia".[218] Fletcher meant "regular" in the sense of regular military, and advocated the universal conscription and regular training of men of fighting age. Jefferson thought well of Fletcher, commenting that "the political principles of that patriot were worthy the purest periods of the British constitution. They are those which were in vigour."[219]

The term "regulated" means "disciplined" or "trained".[220] In Heller, the U.S. Supreme Court stated that "[t]he adjective 'well-regulated' implies nothing more than the imposition of proper discipline and training."[221]

In the year before the drafting of the Second Amendment, in Federalist No. 29 ("On the Militia"), Alexander Hamilton wrote the following about "organizing", "disciplining", "arming", and "training" of the militia as specified in the enumerated powers:[99]

«If a well regulated militia be the most natural defence of a free country, it ought certainly to be under the regulation and at the disposal of that body which is constituted the guardian of the national security ... confiding the regulation of the militia to the direction of the national authority ... [but] reserving to the states ... the authority of training the militia ... A tolerable expertness in military movements is a business that requires time and practice. It is not a day, or even a week, that will suffice for the attainment of it. To oblige the great body of the yeomanry, and of the other classes of the citizens, to be under arms for the purpose of going through military exercises and evolutions, as often as might be necessary to acquire the degree of perfection which would entitle them to the character of a well-regulated militia, would be a real grievance to the people, and a serious public inconvenience and loss ... Little more can reasonably be aimed at, with respect to the People at large, than to have them properly armed and equipped; and in order to see that this be not neglected, it will be necessary to assemble them once or twice in the course of a year.»

Justice Scalia, writing for the Court in Heller:[222]

«In Nunn v. State, 1 Ga. 243, 251 (1846), the Georgia Supreme Court construed the Second Amendment as protecting the 'natural right of self-defence' and therefore struck down a ban on carrying pistols openly. Its opinion perfectly captured the way in which the operative clause of the Second Amendment furthers the purpose announced in the prefatory clause, in continuity with the English right". ... Nor is the right involved in this discussion less comprehensive or valuable: "The right of the people to bear arms shall not be infringed." The right of the whole people, old and young, men, women and boys, and not militia only, to keep and bear arms of every description, not such merely as are used by the militia, shall not be infringed, curtailed, or broken in upon, in the smallest degree; and all this for the important end to be attained: the rearing up and qualifying a well-regulated militia, so vitally necessary to the security of a free State. Our opinion is, that any law, State or Federal, is repugnant to the Constitution, and void, which contravenes this right, originally belonging to our forefathers, trampled under foot by Charles I. and his two wicked sons and successors, reestablished by the revolution of 1688, conveyed to this land of liberty by the colonists, and finally incorporated conspicuously in our own Magna Cha! And Lexington, Concord, Camden, River Raisin, Sandusky, and the laurel-crowned field of New Orleans, plead eloquently for this interpretation! And the acquisition of Texas may be considered the full fruits of this great constitutional right.»

Justice Stevens in dissent:[216]

«When each word in the text is given full effect, the Amendment is most naturally read to secure to the people a right to use and possess arms in conjunction with service in a well-regulated militia. So far as appears, no more than that was contemplated by its drafters or is encompassed within its terms. Even if the meaning of the text were genuinely susceptible to more than one interpretation, the burden would remain on those advocating a departure from the purpose identified in the preamble and from settled law to come forward with persuasive new arguments or evidence. The textual analysis offered by respondent and embraced by the Court falls far short of sustaining that heavy burden. And the Court's emphatic reliance on the claim "that the Second Amendment ... codified a pre-existing right," ante, at 19 [refers to p. 19 of the opinion], is of course beside the point because the right to keep and bear arms for service in a state militia was also a pre-existing right.»

Significato di “diritto del popolo”

[modifica | modifica wikitesto]Justice Antonin Scalia, writing for the majority in Heller, stated: