Utente:Kalumet Sioux/Mammalia: differenze tra le versioni

| Riga 221: | Riga 221: | ||

===Hadrocodium=== |

===Hadrocodium=== |

||

Rispetto ai [[Symmetrodonta|Simmetrodonti]] ed ai [[[[kuehneotheriidae|Kueneoteriidi]], l'''[[Hadrocodium]]'' è considerato un più lontano parente dei veri mammiferi. Ma i fossili dei primi due gruppi sono così pochi e frammentari che risulta difficile capirne le relazioni sistematiche, con l'incertezza che potrebbero essere dei taxa [[parafiletico|parafiletici]]. D'altra parte vi sono buoni fossili di ''Hadrocodium'' (datati circa 195 M.d.a. fa, all'inizio del Giurassico) che recano importanti caratteristiche:<ref>{{cite web | url=http://www.palaeos.com/Vertebrates/Units/Unit420/420.300.html | title=Symmetrodonta - Palaeos}}</ref> |

|||

*l'articolazione mascellare avviene tra lo squamoso ed il dentale, il quale, a differenza dei terapsidi, è l'unico osso della mandibola. |

|||

*The jaw joint consists only of the squamosal and dentary bones, and the jaw contains no smaller bones to the rear of the dentary, unlike the therapsid design. |

|||

*Nei terapsidi ed in molti mammaliformi la [[membrana timpanica]] si tende al di sopra di un'avvallamento della parte posteriore della mandibola. Nell'''Hadrocodium'' non si ha una simile cavità, il che suggerisce che l'[[orecchio]] era parte integrante del cranio (come nei mammiferi), con l'articolare e quadrato migrati nell'orecchio medio a formare il martello e l'incudine. Tuttavia il retro del dentale presenta un'insenatura che manca nei mammiferi. Ciò suggerisce che il suo osso dentale abbia conservato la stessa forma che avrebbe avuto se l'articolare ed il quadrato fossero rimasti a far parte dell'articolazione, e quindi che l'''Hadrocodium'' - od un suo stretto antenato - potrebbero essere stati i primi a possedere un orecchio medio di tipo mammaliano. |

|||

*In [[therapsids]] and most [[mammaliformes]] the [[eardrum]] stretched over a trough at the rear of the lower jaw. But ''Hadrocodium'' had no such trough, which suggests its ear was part of the [[cranium]], as it is in mammals - and hence that the former [[articular]] and [[quadrate]] had migrated to the middle ear and become the [[malleus]] and [[incus]]. On the other hand the dentary has a "bay" at the rear which mammals lack. This suggests that ''Hadrocodium's'' dentary bone retained the same shape that it would have had if the articular and quadrate had remained part of the jaw joint, and therefore that ''Hadroconium'' or a very close ancestor may have been the first to have a fully mammalian middle ear. |

|||

*Therapsids and earlier mammaliforms had their jaw joints very far back in the skull, partly because the ear was at the rear end of the jaw but also had to be close to the brain. This arrangement limited the size of the braincase, because it forced the jaw muscles to run round and over it. ''Hadrocodium's'' braincase and jaws were no longer bound to each other by the need to support the ear, and its jaw joint was further forward. In its descendants or those of animals with a similar arrangement, the brain case was free to expand without being constrained by the jaw and the jaw was free to change without being constrained by the need to keep the ear near the brain - in other words it now became possible for mammal-like animals both to develop large brains and to adapt their jaws and teeth in ways that were purely specialized for eating. |

*Therapsids and earlier mammaliforms had their jaw joints very far back in the skull, partly because the ear was at the rear end of the jaw but also had to be close to the brain. This arrangement limited the size of the braincase, because it forced the jaw muscles to run round and over it. ''Hadrocodium's'' braincase and jaws were no longer bound to each other by the need to support the ear, and its jaw joint was further forward. In its descendants or those of animals with a similar arrangement, the brain case was free to expand without being constrained by the jaw and the jaw was free to change without being constrained by the need to keep the ear near the brain - in other words it now became possible for mammal-like animals both to develop large brains and to adapt their jaws and teeth in ways that were purely specialized for eating. |

||

Versione delle 15:09, 8 mar 2008

- N° approssimativo di voci tassonomiche: 5.500 specie + 1.200 generi + 153 famiglie + 29 ordni + cat intermedie = circa 7.000

- Da fare in Mammalia

- Riproduzione: Apparato riproduttore maschile e femminile, copula, gestazione e parto, allattamento e cure, associazioni sessuali (monogamia e poligamia).

- Comportamento

- Distribuzione

- Ampliare Anatomia dei mammiferi

- ....

- Realizzare una classificazione dei mammiferi per wikipedia.

- Categorie: Costruzione di un'albero ordinato ed inclusione delle cat:nomi comuni.

- Mammiferi fossili: creare voci e cat.

- Altre voci: Formula dentaria, formula vertebrale, patagio....

Evoluzione dei mammiferi

L'evoluzione dei mammiferi dai Sinapsidi ("rettili" simili a mammiferi) fu un graduale processo che durò circa 70 milioni di anni, dal Permiano medio al Giurassico medio. Dal Triassico medio iniziarono a comparire molte specie somiglianti agli attuali mammiferi. Questi ultimi, da un punto di vista filogenetico, possono essere considerati gli unici sinapsidi sopravvissuti.

Definizione di "mammifero"

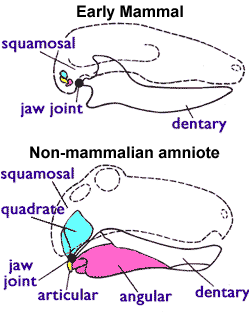

I mammiferi viventi si riconoscono facilmente per la presenza nelle femmine di ghiandole mammarie atte alla produzione del latte. Tuttavia, questa caratteristica non può essere presa in considerazione per la classificazione dei fossili, le cui ghiandole ed altri tessuti molli non sono più presenti. A causa di ciò, i paleontologi usano un'altra caratteristica distintiva, presente a livello scheletrico, che viene mostrata da tutti i mammiferi viventi (inclusi i Monotremi) e che risulta invece assente nei Terapsidi di inizio Triassico: due particolari ossa del cranio, che nei mammiferi hanno una funzione uditiva, negli altri amnioti sono utilizzate per la masticazione.

Infatti, nei primi amnioti l'articolazione tra la mascella e la mandibola si realizza tramite due piccole ossa posizionate nella loro regiore posteriore, chiamate rispettivamente quadrato ed articolare. Questa caratteristica è stata ereditata da tutti gli amnioti non mammiferi, come le lucertole, i coccodrilli, i dinosauri, gli uccelli ed i terapsidi.

Nei mammiferi si ha invece una differente articolazione, che avviene tra il dentale (l'unico osso che costituisce la mandibola) e la porzione squamosa dell'osso temporale, mentre il quadrato e l'articolare si ritrovano nell'orecchio medio, dove diventano ripettivamente l'incudine ed il martello.[1][2]

Proprio queste peculiarità ci permettono di riconoscere e distinguere un mammifero, vivente o fossile, da un qualsiasi altro vertebrato.

Gli antenati dei mammiferi

Qui di seguito viene mostrato un albero filogenetico semplificato che mostra il percorso evolutivo, da un progenitore tetrapode alla formazione del primo mammifero.

--Tetrapodi-------------------------------------------------- | +-- Anfibi--------------------------------------- | `--Amnioti----- | +--Sauropsidi------------------------------------ | `--Sinapsidi------ | `--Pelicosauri---- | `--Terapsidi----- | `--Mammiferi------------------

Amnioti

Gli Amnioti furono i primi vertebrati perfettamente adattati alla vita terrestre. L'indipendenza dalla'ambiente acquatico si ottenne grazie alla produzione di uova dotate di membrane interne (amnios, corion ed allantoide) e guscio protettivo, che permisero all'embrione di svilupparsi, consentendo la respirazione e, allo stesso tempo, mantenendo una certa quantità d'acqua al suo interno. In questo modo le uova poterono essere depositate in ambienti secchi, a differenza degli Anfibi, legati agli ambienti acquatici per evitarne l'essicazione. Solo pochi anfibi, come il rospo del Suriname, hanno evoluto strategie diverse per porre rimedio a questa limitazione.

I primi amnioti apparvero intorno al tardo Carbonifero, da rettiliomorfi ancestrali. In pochi milioni di anni, da essi si distinsero due importanti linee evolutive: i Sauropsidi, dai quali discesero i Rettili e gli Uccelli, e quella dei Sinapsidi, progenitori dei Mammiferi.[3]

I più antichi fossili appartenenti a questi due gruppi risalgono a circa 320-315 m.d.a. Sfortunatamente, per la rarità di fossili di vertebrati del tardo Carbonifero, risulta difficile stabilire quando ognuno di essi si possa essere evoluto e, quindi, quale dei due gruppi apparve per primo.[4]

Sinapsidi

I crani degli Sinapsidi vengono identificati grazie alla presenza di una sola coppia di finestre temporali, ciascuna sita nella regione posteriore rispetto alla fossa orbitaria.

Queste permettevano di:

- rendere il cranio più leggero senza sacrificare la sua solidità;

- risparmiare energia non destinandola alla formazione di una parte di tessuto osseo.

- servire da punti d'attacco per i muscoli masticatori, i quali poterono svilupparsi maggiormente e così esercitare una forma maggiore senza eccedere nello sforzo derivato dalla loro continua contrazione ed espansione.

Dai dati paleontologici risulta che i Pelicosauri furono il principale gruppo di sinapsidi dell'inizio Permiano, rappresentando i più grandi animali terrestri di quel tempo.[5]

Terapsidi

I Terapsidi si originarono nel Permiano medio da pelicosauri della famiglia degli Sfenacodontidi, sostituendoli nel ruolo di vertebrati dominanti dell'ambiente sub-aereo. Questi nuovi sinapsidi differivano per alcune caratteristiche del cranio e delle mascelle, inclusi un'ampia finestra temporale e tutti gli incisivi di uguale dimensione.[6]

Nel corso della loro storia, i terapsidi attraversarono una serie di stadi evolutivi, passando da forme iniziali, simili ai loro antenati pelicosauri, a forme finali facilmente confondibili con i veri mammiferi. Ciò si deve ad:[7]

- un graduale sviluppo di un palato osseo secondario. Vari autori interpretano ciò come un requisito fondamentale per l'evoluzione dell'elevato ritmo metabolico presente nei mammiferi, poichè consente a questi animali di masticare e respirare contemporanemente, grazie all'arretramento delle coane. Tuttavia, alcuni scienziati puntualizzano che alcuni moderni ectotermi sono dotati di un palato secondario carnoso per separare la bocca dalla via respiratoria, e che un palato osseo funge da superficie sulla quale la lingua può manipolare meglio il cibo, facilitando più la masticazione che la respirazione.[8] Anche quest'ultima interpretazione suggerisce lo sviluppo di un metabolismo più veloce, dato che una migliore masticazione consente di digerire il cibo più rapidamente. Nei mammiferi il palato è formato da due ossa specifiche, ma vari terapsidi del Permiano mostravano altre combinazioni di ossa che, presenti nei posti giusti, formavano il palato.

- Il dentale diventa gradualmente il principale osso della mandibola.

- un progressivo raddrizzamento della postura degli arti, che avrebbe aumentato la resistenza dell'organismo contrastando la costrizione di Carrier. Comunque, questo processo fu molto lento ed irregolare, come testimoniato dagli arti curvi di molti terapsidi del Permiano e anche dei Monotremi moderni.

- un graduale perfezionamento della mascella e dell'orecchio medio, nel Triassico.

- Prove plausibili della presenza del pelo nei terapsidi del Triassico (vedi più avanti nel testo)

- Segni di allattamento sempre nel Triassico, secondo alcuni scienziati (vedi avanti).

Albero filogenetico dei Terapsidi

(semplificazione di [9]; vengono mostrati solo i taxa più rilevanti per l'evoluzione dei mammiferi)

Terapsidi | +--Biarmosuchi | `--+--Dinocefali | +--Neoterapsidi | +--Anomodonti | | | `--Dicinodonti | `--+--Teriodonti | +--Gorgonopsi | `--+--Terocefali | `--Cinodonti . . . . Mammiferi

Di questi, solo i Dicinodonti, Terocefali e Cinodonti sopravvissero nel Triassico.

Biarmosuchia

I Biarmosuchi furono i terapsidi più primiti e somiglianti ai Pelicosauri.

Dinocefali

I Dinocefali (letteralmente "teste terribili") erano terapsidi di grandi dimensioni, alcuni quanto un rinoceronte, e comprendevano sia forme carnivore che erbivore. Parte dei carnivori mostrava una postura semi-eretta. Tuttavia, rimanevano terapsidi molto primitivi per l'assenza di un palato secondario e per le mascelle più simili al "tipo rettiliano".[10]

Anomodonti

Tra i terapsidi erbivori, gli Anomodonti ("denti anomali") furono quelli ad aver più successo. Un suo sottogruppo, i Dicinodonti, sopravvissero fino a quasi la fine del Triassico. Comunque, questi animali erano molto diversi dai mammiferi erbivori moderni: gli unici denti che possedevano erano un paio zanne allogiate nella mascella superiore ed è generalmentre accettato che avessero anche di un becco, simile a quello degli Uccelli (o dei Ceratopsidi).[11]

Teriodonti

I Teriodonti ("denti bestiali") ed i loro discendenti possedevano una mandibola con l'osso articolare saldamente connesso al cranio tramite un piccolo osso quadrato. Ciò permetteva una maggiore apertura boccale e ad un gruppo di essi, i carnivori Gorgonopsi ("aspetto di gorgone"), di poter sviluppare dei "denti a sciabola". L'articolazione mascellare dei Teriodonti ebbe una grande importanza nel lungo termine, poichè la riduzione del quadrato fu un passaggio fondamentale per lo sviluppo dell'articolazione mascellare e dell'orecchio medio, tipici dei Mammiferi. I Gorgonopsi mostravano anche caratteristiche primitive, come la mancanza di un palato osseo secondario ed arti non eretti.

Nello stesso periodo in cui vissero i Gorgonopsi, apparve un altro gruppo di teriodonti, i Terocefali ("teste bestiali"), i quali mostravano altri caratteri simili ai mammiferi, come ad esempio ossa delle dita con un numero fisso di falangi, identico a quello dei mammiferi più primitivi (inclusi i Primati e quindi anche l'uomo).[12]

Cinodonti

I Cinodonti ("denti di cane"), furono un gruppo di teriodonti comparso nel tardo Permiano, al cui interno vengono inclusi i progenitori di tutti i mammiferi, da ricercare molto probabilmente tra i membri della famiglia dei Tritelodontidi.

Tra le caratteristiche di tipo mammaliano: ulteriore riduzione del numero di ossa della mandibola; un palato osseo secondario; denti masticatori con un complesso modello di corone; il cervello che occupa interamente la cavità endocraniale.[13]

L'acquisizione del Triassico

La catastrofica estinzione di massa, avvenuta durante il passaggio dal Permiano al Triassico, portò alla scomparsa sulla terraferma di circa il 70% delle specie di vertebrati e di gran parte delle piante terrestri. Di conseguenza avvenne che:[14]

- gli ecosistemi e le catene alimentari collassarono e per il loro ripristino ci vollero circa 6 m.d.a.

- i sopravvissuti dovettero reingaggiare la lotta per rioccupare le precedenti nicchie ecologiche, compresi i Cinodonti, i quali sembravano stessero raggiungendo il predominio alla fine del Permiano.

Nel corso del Triassico, i Cinodonti furono però soppiantati da un gruppo di sauropsidi in precedenza sconosciuto, gli Arcosauri, rettili diapsidi che includevano i progenitori dei coccodrilli, dinosauri ed uccelli. Questo rovesciamento delle sorti viene spesso chiamato Triassic takeover ("l'acquisizione del Triassico"). La più probabile spiegazione di questo evento fu la predominante aridità instauratasi all'inizio del Triassico e quindi il vantaggio degli arcosauri nel riuscire a trattenere maggiormente l'acqua: tutti i sauropsidi conosciuti hanno infatti una pelle povera di ghiandole ed espellono acido urico, che richiede minore quantità d'acqua per la sua produzione rispetto all'urea secreta dai mammiferi (e presumibilmente dai loro progenitori terapsidi).[15][7] La scalata del Triassico fu comunque un processo graduale: i Cinodonti furono inizialmente i principali predatori ed i listrosauri gli erbivori dominanti, ma nel Triassico medio gli Arcosauri occuparono tutte le principali nicchie ecologiche, erbivore e carnivore.

Senza dubbio, il successo degli Arcosauri fu un fattore determinante per l'evoluzione dei mammiferi dai Cinodonti, poichè questi poterono sopravvivere solo come piccoli insettivori principalmente notturni.[16] Le principali conseguenze, dettate dalla pressione selettiva, furono:

- la tendenza alla diversificazione dei denti (eterodontia) ed alla loro occlusione, per la cattura degli Artropodi e la frantumazione del loro esoscheletro.

- la necessità di provvedere all'isolamento termico ed alla termoregolazione per essere più attivi durante fredde notti.

- lo sviluppo di un acuto senso dell'olfatto e dell'udito, divenuti d'importanza vitale.

- ciò provocò la formazione dell'orecchio medio mammaliano e quindi dell'articolazione mascellare per la trasformazione morfo-funzionale di quadrato ed articolare.

- l'aumento delle dimensioni dei lobi olfattivi ed uditivi del cervello aumentò il peso percentuale di quest'ultimo rispetto alla massa corporea. I tessuti cerebrali richiesero così una spropositata quantità di energia.[17][18] La necessità di procurarsi più cibo per supportare un grande cervello aumentò la pressione selettiva per provvedere all'isolamento termico, alla termoregolazione ed alla predazione.

- il senso della vista divenne leggermente meno importante e ciò riflette il fatto che molti mammiferi hanno una scarsa percezione dei colori, inclusi i primati più primitivi come i lemuri.[19]

Dai cinodonti ai veri mammiferi

Le incertezze

Se da un lato le vicende del Triassico accelerarono l'evoluzione dei mammiferi, dall'altro rese più difficile la vita dei paleontologi per la rarità di buoni fossili, dovuto al fatto che i "quasi mammiferi" avevano spesso dimensioni più piccole di quelle di un ratto moderno. Inoltre:

- Erano ristretti ad ambienti con rare probabilità di fornire buoni fossili. I migliori ambienti terrestri per la fossilizzazione sono senz'altro gli alvei dei fiumi, dove le inondazioni stagionali ricoprono gli animali morti con uno strato protettivo di silt, che sarà poi compresso a formare le rocce sedimentarie (diagenesi). Questi ambienti erano però dominati da animali di più grossa mole, cioè gli Arcosauri.

- Le loro delicate ossa venivano più facilmente distrutte prima che si potessero fossilizzare, per l'azione dei saprofagi (inclusi funghi e batteri) e del calpestìo da parte di altri animali.

- I piccoli fossili sono più difficili da trovare e più vulnerabili all'erosione e ad altri stress naturali.

Per queste motivazioni è stato ipotizzato che tutti i fossili del Mesozoico di mammiferi e dei loro parenti più prossimi potrebbero essere contenuti in poche scatole di scarpe, e molti di essi sono solo denti, molto più resistenti e duraturi di tutti gli altri tessuti.[20]

Di conseguenza risulta che:

- In molti casi è difficile assegnarli ad un determinato genere.

- Tutti i fossili disponibili di un genere riescono raramente a riprodurre uno scheletro completo e quindi diventa difficile stabilire quali generi siano più simili morfologicamente e più vicini filogeneticamente, rendendo ardua la classificazione ottenuta tramite i principi della cladistica.

Tuttavia, anche se l'evoluzione dei mammiferi nel Mesozoico è piena di incertezze, non vi sono dubbi che i veri mammiferi apparvero in questa era geologica.

Mammiferi o Mammaliformi?

Una conseguenza di queste incertezze fu il cambiamento della definizione paleontologica del termine "mammifero". Per lungo tempo un fossile veniva incluso nella classe Mammalia se rispettava i criteri già illustrati sulla conformazione delle mascelle e dell'orecchio medio. Recentemente però i paleontologi sono soliti considerare mammiferi soltanto i Monotremi, i Marsupiali, gli Euplacentati e tutti i loro antenati fino al progenitore che ebbero in comune. Tutti i fossili che mostrano caratteri più simili ai mammiferi che ai cinodonti, ma che risultano fileticamente lontani dai mammiferi viventi, invece vengono ascritti al clade Mammaliaformes.[21]

Sebbene la distinzione appena descritta sembri essere quella più adottata, alcuni paleontologi diffidano da essa perché: molti problemi vengono trasferiti nel nuovo clade senza che possano essere risolti; il clade contiene alcuni animali con mascelle mammaliane ed altri di tipo rettiliano (cioè con l'articolare giunto al quadrato); le nuove definizioni di mammifero e mammaliforme dipendono dagli antenati comuni ad entrambi i gruppi, i quali non sono ancora stati ritrovati.[22]

A dispetto di queste obiezioni, questa voce si allinea all'approccio più seguito e tratta molti dei discendenti mesozoici dei cinodonti come mammaliformes.

Albero filetico: Cinodonti - Mammiferi

(semplificazione basata su Mammaliformes - Palaeos)

--Cynodontia | `--Mammaliaformes | +--Allotheria | | | `--Multituberculata | `--+--Morganucodontidae | `--+--Docodonta | `--+--Hadrocodium | `--Symmetrodonta | |--Kuehneotheriidae | `--Mammalia

Multitubercolati

I Multitubercolati, così chiamati per i molteplici tubercoli dei loro molari, sono un evidente esempio di convergenza evolutiva con i membri dell'ordine Rodentia, tant'è che vengono soprannominati impropriamnete "roditori del Mesozoico", sebbene questi due taxa siano filogeneticamente molto distanti.

A prima vista, la loro morfologia è simile a quella dei mammiferi: mandibola costituita dal solo dentale ed articolata con lo squamoso; quadrato ed articolare partecipano alla conformazione dell'orecchio medio; denti differenziati, occlusi e con cuspidi di tipo mammaliano; presenza dell'arco zigomatico; bacino con struttura che suggerisce il parto di piccoli neonati indifesi, come nei marsupiali moderni.

Questo gruppo visse per oltre 120 M.d.a. (dal Giurassico medio all'Oligocene inferiore), estinguendosi circa 35 M.d.a. fa. Ciò li renderebbe i mammiferi di maggior successo in assoluto, se, guardandoli più da vicino, non mostrassero delle notevoli differenze rispetto ai mammiferi moderni:[23]

- I loro molari possiedono due file parallele di tubercoli, anzichè essere tribosfenici come nei primi mammiferi.

- L'azione masticatoria è completamente differente: nei mammiferi la triturazione avviene lateralmente, con i molari che occludono in un solo lato per volta; le mascelle dei multitubercolati erano invece incapaci di questo movimento laterale e trituravano con i denti inferiori che premevano all'indietro contro i superiori.

- La parte anteriore dell'arco zigomatico è costituito principalmente dal mascellare e non dal giugale, che risulta essere invece un minuscolo osso formante il processo mascellare.

- L'osso squamoso non forma parte della scatola cranica.

- Il muso (o rostro) è più simile a quello dei pelicosauri, come Dimetrodon, che a quello dei mammiferi. È simile ad una scatola, con un largo e piatto mascellare che forma i lati, l'osso nasale il sopra ed il premascellare la zona frontale.

Morganucodontidi

I Morganucodontidi apparvero nel tardo Triassico, circa 205 M.d.a fa, e sono un eccellente esempio di fossili di transizione, per la presenza nel gruppo di entrambe le tipologie di giunture mascellari (dentale-squamoso e quadrato-articolare).[24] Inoltre, furono i primi mammaliformi ad essere scoperti e, tra questi, i più studiati approfonditamente per il gran numero di fossili ritrovati.

Docodonti

Il genere più noto dei Docodonti è Castorocauda ("coda di castoro"), che visse nel Giurassico medio, circa 164 M.d.a. fa, e fu scoperto nel 2004 per poi essere descritto nel 2006.[25] Castorocauda non era un tipico docodonte, molti dei quali erano onnivori, ne un vero mammifero, ma risulta comunque importante per lo studio dell'evoluzione dei mammiferi, perché ne fu ritrovato uno scheletro quasi completo (un vero lusso in paleontologia) e con esso viene superato lo stereotipo del "piccolo insettivoro notturno":

- Era più grande degli altri fossili dei quasi-mammiferi mesozoici: lungo 43 cm dal muso alla coda (13 cm) e dal peso di circa 800 gr.

- È la più antica testimonianza della presenza del pelo e della pelliccia. Prima della sua scoperta il titolo spettava ad Eomaia, un vero mammifero di circa 125 M.d.a. fa.

- Presentava adattamenti alla vita acquatica, come la coda appiattita e rimasugli di soffici tessuti fra le dita delle zampe posteriori che ne suggeriscono la palmazione. Dopo di esso, il più antico mammaliforme semi-acquatico conosciuto risale all'Eocene, circa 110 M.d.a. fa.

- I suoi robusti arti sembrano adattati all'attività di scavo. Per questa caratteristica e per gli speroni sulle caviglie, Castorocauda mostra una straordinaria somiglianza con l'ornitorinco, anch'esso nuotatore e scavatore.

- I suoi denti sembrano adatti ad una dieta piscivora: i primi due molari hanno cuspidi in fila retta, più idonei ad afferrare e tagliare che a triturare, e sono curvati all'indietro per aiutare a trattenere la preda scivolosa.

Hadrocodium

Rispetto ai Simmetrodonti ed ai [[Kueneoteriidi, l'Hadrocodium è considerato un più lontano parente dei veri mammiferi. Ma i fossili dei primi due gruppi sono così pochi e frammentari che risulta difficile capirne le relazioni sistematiche, con l'incertezza che potrebbero essere dei taxa parafiletici. D'altra parte vi sono buoni fossili di Hadrocodium (datati circa 195 M.d.a. fa, all'inizio del Giurassico) che recano importanti caratteristiche:[26]

- l'articolazione mascellare avviene tra lo squamoso ed il dentale, il quale, a differenza dei terapsidi, è l'unico osso della mandibola.

- Nei terapsidi ed in molti mammaliformi la membrana timpanica si tende al di sopra di un'avvallamento della parte posteriore della mandibola. NellHadrocodium non si ha una simile cavità, il che suggerisce che l'orecchio era parte integrante del cranio (come nei mammiferi), con l'articolare e quadrato migrati nell'orecchio medio a formare il martello e l'incudine. Tuttavia il retro del dentale presenta un'insenatura che manca nei mammiferi. Ciò suggerisce che il suo osso dentale abbia conservato la stessa forma che avrebbe avuto se l'articolare ed il quadrato fossero rimasti a far parte dell'articolazione, e quindi che lHadrocodium - od un suo stretto antenato - potrebbero essere stati i primi a possedere un orecchio medio di tipo mammaliano.

- Therapsids and earlier mammaliforms had their jaw joints very far back in the skull, partly because the ear was at the rear end of the jaw but also had to be close to the brain. This arrangement limited the size of the braincase, because it forced the jaw muscles to run round and over it. Hadrocodium's braincase and jaws were no longer bound to each other by the need to support the ear, and its jaw joint was further forward. In its descendants or those of animals with a similar arrangement, the brain case was free to expand without being constrained by the jaw and the jaw was free to change without being constrained by the need to keep the ear near the brain - in other words it now became possible for mammal-like animals both to develop large brains and to adapt their jaws and teeth in ways that were purely specialized for eating.

The earliest true mammals

This part of the story introduces new complications, since true mammals are the only group which still has living members:

- One has to distinguish between extinct groups and those which have living representatives.

- One often feels compelled to try to explain the evolution of features which do not appear in fossils. This endeavor often involves Molecular phylogenetics, a technique which has become popular since the mid-1980s but is still often controversial because of its assumptions, especially about the reliability of the molecular clock.

Family tree of early true mammals

(based on Mammalia: Overview - Palaeos; X marks extinct groups)

--Mammals | +--Australosphenida | | | +--Ausktribosphenidae X | | | `--Monotremes | `--+--Triconodonta X | `--+--Spalacotheroidea X | `--Cladotheria | |--Dryolestoidea X | `--Theria | +--Metatheria | `--Eutheria

Australosphenida and Ausktribosphenidae

Ausktribosphenidae is a group name that has been given to some rather puzzling finds which:[27]

- appear to have tribosphenic molars, a type of tooth which is otherwise known only in placentals.

- come from mid Cretaceous deposits in Australia - but Australia was connected only to Antarctica, and placentals originated in the northern hemisphere and were confined to it until continental drift formed land connections from North America to South America, from Asia to Africa and from Asia to India (the late Cretaceous map at [1] shows how the southern continents are separated).

- are represented only by skull and jaw fragments, which is not very helpful.

Australosphenida is a group which has been defined in order to include the Ausktribosphenidae and monotremes. Asfaltomylos (mid- to late Jurassic, from Patagonia) is apparently a basal australosphenid (animal which: has features shared with both Ausktribosphenidae and monotremes; lacks features which are peculiar to Ausktribosphenidae or monotremes; also lacks features which are absent in Ausktribosphenidae and monotremes) and shows that australosphenids were wide-spread throughout Gondwanaland (the old Southern hemisphere super-continent).[28]

Monotremes

The earliest known monotreme is Teinolophos, which lived about 123M years ago in Australia. Monotremes have some features which may be inherited from the original amniotes:

- they use the same orifice to urinate, defecate and reproduce ("monotreme" means "one hole") - as lizards and birds also do.

- they lay eggs which are leathery and uncalcified, like those of lizards, turtles and crocodilians.

Unlike in other mammals, female monotremes do not have nipples and feed their young by "sweating" milk from patches on their bellies.

Of course these features are not visible in fossils, and the main characteristics from paleontologists' point of view are:[29]

- a slender dentary bone in which the coronoid process is small or non-existent.

- the external opening of the ear lies at the posterior base of the jaw.

- the jugal bone is small or non-existent.

- a primitive pectoral girdle with strong ventral elements: coracoids, clavicles and interclavicle. Note: therian mammals have no interclavicle.[30]

- sprawling or semi-sprawling forelimbs.

Theria

Theria ("beasts") is a name applied to the hypothetical group from which both metatheria (which include marsupials) and eutheria (which include placentals) descended. Although no convincing fossils of basal therians have been found (just a few teeth and jaw fragments), metatheria and eutheria share some features which one would expect to have been inherited from a common ancestral group:[31]

- no interclavicle.[32]

- coracoid bones non-existent or fused with the shoulder blades to form coracoid processes.

- tribosphenic molars.

- a type of crurotarsal ankle joint in which: the main joint is between the tibia and astragalus; the calcaneum has no contact with the tibia but forms a heel to which muscles can attach. (The other well-known type of crurotarsal ankle is seen in crocodilians and works differently - most of the bending at the ankle is between the calcaneum and astragalus).

Metatheria

The living Metatheria are all marsupials ("animals with pouches"). A few fossil genera such as the Mongolian late Cretaceous Asiatherium may be marsupials or members of some other metatherian group(s).[33][34]

The oldest known marsupial is Sinodelphys, found in 125M-year old early Cretaceous shale in China's northeastern Liaoning Province. The fossil is nearly complete and includes tufts of fur and imprints of soft tissues.[35]

Didelphimorphia (common opossums of the Western Hemisphere) first appeared in the late Cretaceous and still have living representatives, probably because they are mostly semi-arboreal unspecialized omnivores.[36]

The best-known feature of marsupials is their method of reproduction:

- The mother develops a kind of yolk sack in her womb which delivers nutrients to the embryo. Embryos of bandicoots, koalas and wombats additionally form placenta-like organs that connect them to the uterine wall, although the placenta-like organs are smaller than in placental mammals and it is not certain that they transfer nutrients from the mother to the embryo.[37]

- Pregnancy is very short, typically 4 to 5 weeks. The embryo is born at a very young age of development, and is usually less than 2 inches (5cm) long at birth. It has been suggested that the short pregnancy is necessary to reduce the risk that the mother's immune system will attack the embryo.

- The newborn marsupial uses its forelimbs (with relatively strong hands) to climb to a nipple, which is usually in a pouch on the mother's belly. The mother feeds the baby by contracting muscles over her mammary glands, as the baby is too weak to suck. The newborn marsupial's need to use its forelimbs in climbing to the nipple has prevented the forelimbs from evolving into paddles or wings and has therefore prevented the appearance of aquatic or truly flying marsupials (although there are several marsupial gliders).

Although some marsupials look very like some placentals (the thylacine or "marsupial wolf" is a good example), marsupial skeletons have some features which distinguish them from placentals:[38]

- Some, including the thylacine, have 4 molars. No placentals have more than 3.

- All have a pair of palatal fenestrae, window-like openings on the bottom of the skull (in addition to the smaller nostril openings).

Marsupials also have a pair of marsupial bones (sometimes called "epipubic bones"), which support the pouch in females. But these are not unique to marsupials, since they have been found in fossils of multituberculates, monotremes, and even eutherians - so they are probably a common ancestral feature which disappeared at some point after the ancestry of living placental mammals diverged from that of marsupials.[39][40] Some researchers think the epipubic bones' original function was to assist locomotion by supporting some of the muscles that pull the thigh forwards.[41]

Eutheria

The living Eutheria ("true beasts") are all placentals. But the earliest known eutherian, Eomaia, found in China and dated to 125M years ago, has some features which are more like those of marsupials (the surviving metatherians):[42]

- Epipubic bones extending forwards from the pelvis, which are not found in any modern placental, but are found in marsupials, monotremes and mammaliformes such as multituberculates. In other words, they appear to be an ancestral feature which may even have been present in the earliest placentals.

- A narrow pelvic outlet, which indicates that the young were very small at birth and therefore pregnancy was short, as in modern marsupials. This suggests that the placenta was a later development.

- 5 incisors in each side of the upper jaw. This number is typical of metatherians, and the maximum number in modern placentals is 3, except for homodonts such as the armadillo. But Eomaia's molar to premolar ratio (it has more pre-molars than molars) is typical for eutherians (placentals) and not normal in marsupials.

Eomaia also has a Meckelian groove, a primitive feature of the lower jaw which is not found in modern placental mammals.

These intermediate features are consistent with molecular phylogenetics estimates that the placentals diversified about 110M years ago, 15M years after the date of the Eomaia fossil.

Eomaia also has many features which strongly suggest it was a climber, including: several features of the feet and toes; well-developed attachment points for muscles which are used a lot in climbing; and a tail which is twice as long as the rest of the spine.

Placentals' best-known feature is their method of reproduction:

- The embryo attaches itself to the uterus via a large placenta via which the mother supplies food and oxygen and removes waste products.

- Pregnancy is relatively long and the young are fairly well-developed at birth. In some species (especially herbivores living on plains) the young can walk and even run within an hour of birth.

It has been suggested that the evolution of placental reproduction was made possible by retroviruses which:[43]

- make the interface between the placenta and uterus into a syncytium, i.e. a thin layer of cells with a shared external membrane. This allows the passage of oxygen, nutrients and waste products but prevents the passage of blood and other cells which would cause the mother's immune system to attack the foetus.

- reduce the aggressiveness of the mother's immune system (which is good for the foetus but makes the mother more vulnerable to infections).

From a paleontologist's point of view, eutherians are mainly distinguished by various features of their teeth.[44]

Expansion of ecological niches in the Mesozoic

There is still some truth in the "small, nocturnal insectivores" stereotype but recent finds, mainly in China, show that some mammaliforms and true mammals were larger and had a variety of lifestyles. For example:

- Castorocauda, which lived in the mid Jurassic about 164M years ago, was about 17 inches (43 cm) long, weighed up to 1.75 pounds (800 grams), had limbs which were adapted for swimming and digging and teeth adapted for eating fish.[45]

- Multituberculates, which survived for over 120 million years (from mid Jurassic, about 160M years ago, to early Oligocene, about 35M years ago) are often called the "rodents of the Mesozoic", because they had continuously-growing incisors like those of modern rodents.[46]

- Fruitafossor, from the late Jurassic period about 150 million years ago, was about the size of a chipmunk and its teeth, forelimbs and back suggest that it broke open the nest of social insects to prey on them (probably termites, as ants had not yet appeared).[47]

- Volaticotherium, from the boundary between the late Jurassic and early Cretaceous about 140-120M years ago, is the earliest-known gliding mammal and had a gliding membrane which stretched out between its limbs, rather like that of a modern flying squirrel. This also suggests it was active mainly during the day.[48]

- Repenomamus, from the Early Cretaceous 128–139M years ago, was a stocky, badger-like predator which sometimes preyed on young dinosaurs. Two species have been recognized, one more than 1 m (3 ft) long and weighing about 12–14 kg, the other less than 0.5 m (20 in) long and weighing 4–6 kg (9–13 lb).[49][50]

Evolution of major groups of living mammals

There are currently vigorous debates between traditional paleontologists ("fossil-hunters") and molecular phylogeneticists about how and when the true mammals diversified, especially the placentals. Generally the traditional paelontologists date the appearance of a particular group by the earliest known fossil whose features make it likely to be a member of that group, while the molecular phylogeneticists suggest that each lineage diverged earlier (usually in the Cretaceous) and that the earliest members of each group were anatomically very similar to early members of other groups and differed only in their genes. These debates extend to the definition of and relationships between the major groups of placentals - the controversy about Afrotheria is a good example.

Fossil-based family tree of placental mammals

Here is a very simplified version of a typical family tree based on fossils, based on Cladogram of Mammalia - Palaeos. It tries to show the nearest thing there is at present to a consensus view, but some paleontologists have very different views, for example:[51]

- The most common view is that placentals originated in the southern hemisphere, but some paleontologists argue that they first appeared in Laurasia (old supercontinent containing modern Asia, N. America and Europe).

- Paleontologists differ about when the first placentals appeared, with estimates ranging from 20M years before the end of the Cretaceous to just after the end of the Cretaceous. And molecular biologists argue for a much earlier origin.

- Most paleontologists suggest that placentals should be divided into Xenarthra and the rest, but a few think these animals diverged later.

For the sake of brevity and simplicity the diagram omits some extinct groups in order to focus on the ancestry of well-known modern groups of placentals - X marks extinct groups. The diagram also shows:

- the age of the oldest known fossils in many groups, since one of the major debates between traditional paleontologists and molecular phylogeneticists is about when various groups first became distinct.

- well-known modern members of most groups.

--Eutheria | +--Xenarthra (Paleocene) | (armadillos, anteaters, sloths) | `--+--Pholidota (early Eocene) | (pangolins) | `--Epitheria (late Cretaceous) | |--(some extinct groups) X | `--+--Insectivora (late Cretaceous) | (hedgehogs, shrews, moles, tenrecs) | `--+--+--Anagalida | | | | | +--Zalambdalestidae X (late Cretaceous) | | | | | `--+--Macroscelidea (late Eocene) | | | (elephant shrews) | | | | | `--+--Anagaloidea X | | | | | `--Glires (early Paleocene) | | | | | +--Lagomorpha (Eocene) | | | (rabbits, hares, pikas) | | | | | `--Rodentia (late Paleocene) | | (mice & rats, squirrels, | | porcupines) | | | `--Archonta | | | |--+--Scandentia (mid [Eocene]) | | | (tree shrews) | | | | | `--Primatomorpha | | | | | +--Plesiadapiformes X | | | | | `--Primates (early Paleocene) | | (tarsiers, lemurs, monkeys, | | apes, humans) | | | `--+--Dermoptera (late Eocene) | | (colugos) | | | `--Chiroptera (late Paleocene) | (bats) | `--+--Ferae (early Paleocene) | (cats, dogs, bears, seals) | `--Ungulatomorpha (late Cretaceous) | +--Eparctocyona (late Cretaceous) | | | +--(some extinct groups) X | | | `--+--Arctostylopida X (late Paleocene) | | | `--+--Mesonychia X (mid Paleocene) | | (predators / scavengers, | | but not closely related | | to modern carnivores) | | | `--Cetartiodactyla | | | +--Cetacea (early Eocene) | | (whales, dolphins, porpoises) | | | `--Artiodactyla (early Eocene) | (even-toed ungulates: | pigs, hippos, camels, | giraffes, cattle, deer) | `--Altungulata | +--Hilalia X | `--+--+--Perissodactyla (late Paleocene) | | (odd-toed ungulates: | | horses, rhinos, tapirs) | | | `--Tubulidentata (early Miocene) | (aardvarks) | `--Paenungulata ("not quite ungulates") | +--Hyracoidea (early Eocene) | (hyraxes) | `--+--Sirenia (early Eocene) | (manatees, dugongs) | `--Proboscidea (early Eocene) (elephants)

This family tree contains some surprises and puzzles. For example:

- The closest living relatives of cetaceans (whales, dolphins, porpoises) are artiodactyls, hoofed animals which are almost all pure vegetarians.

- Bats are fairly close relatives of primates.

- The closest living relatives of elephants are the aquatic sirenians, while their next relatives are hyraxes, which look more like well-fed guinea pigs.

- There is little correspondence between the structure of the family (what was descended from what) and the dates of the earliest fossils of each group. For example the earliest fossils of perissodactyls (the living members of which are horses, rhinos and tapirs) date from the late Paleocene but the earliest fossils of their "sister group" the Tubulidentata date from the early Miocene, nearly 50M years later. Paleontologists are fairly confidents about the family relationships, which are based on cladistic analyses, and believe that fossils of the ancestors of modern aardvarks have simply not been found yet.

Family tree of placental mammals according to molecular phylogenetics

Molecular phylogenetics uses features of organisms' genes to work out family trees in much the same way as paleontologists do with features of fossils - if two organisms' genes are more similar to each other than to those of a third organism, the two organisms are more closely related to each other than to the third.

Molecular phylogeneticists have proposed a family tree which is very different from the one with which paleontologists are familiar. Like paleontologists, molecular phylogeneticists have different ideas about various details, but here is a typical family tree according to molecular phylogenetics:[52][53] Note that the diagram shown here omits extinct groups, as one cannot extract DNA from fossils.

--Eutheria | +--Atlantogenata ("born round the Atlantic ocean") | | | +--Xenarthra (armadillos, anteaters, sloths) | | | `--Afrotheria | | | +--Afroinsectiphilia | | (golden moles, tenrecs, otter shrews) | | | +--Pseudungulata ("false ungulates") | | | | | +--Macroscelidea (elephant shrews) | | | | | `--Tubulidentata (aardvarks) | | | `--Paenungulata ("not quite ungulates") | | | +--Hyracoidea (hyraxes) | | | +--Proboscidea (elephants) | | | `--Sirenia (manatees, dugongs) | `--Boreoeutheria ("northern true / placental mammals") | +--Laurasiatheria | | | +--Erinaceomorpha (hedgehogs, gymnures) | | | +--Soricomorpha (moles, shrews, solenodons) | | | +--Cetartiodactyla | | (cetaceans and even-toed ungulates) | | | `--Pegasoferae | | | +--Pholidota (pangolins) | | | +--Chiroptera (bats) | | | +--Carnivora (cats, dogs, bears, seals) | | | `--Perissodactyla (horses, rhinos, tapirs). | `--Euarchontoglires | +--Glires | | | +--Lagomorpha | | (rabbits, hares, pikas) | | | `--Rodentia (late Paleocene) | (mice & rats, squirrels, porcupines) | `--Euarchonta | |--Scandentia (tree shrews) | |--Dermoptera (colugos) | `--Primates (tarsiers, lemurs, monkeys, apes)

The most significant of the many differences between this family tree and the one familiar to paleontologists are:

- The top-level division is between Atlantogenata and Boreoeutheria, instead of between Xenarthra and the rest. But some molecular phylogeneticists have proposed a 3-way top-level split between Xenarthra, Afrotheria and Boreoeutheria.

- Afrotheria contains several groups which are only distantly related according to the paleontologists' version: Afroinsectiphilia ("African insectivores"), Tubulidentata (aardvarks, which paleontologists regard as much closer to odd-toed ungulates than to other members of Afrotheria), Macroscelidea (elephant shrews, usually regarded as close to rabbits and rodents). The only members of Afrotheria which paleontologists would regard as closely related are Hyracoidea (hyraxes), Proboscidea (elephants) and Sirenia (manatees, dugongs).

- Insectivores are split into 3 groups: one is part of Afrotheria and the other two are distinct sub-groups within Boreoeutheria.

- Bats are closer to Carnivora and odd-toed ungulates than to primates and Dermoptera (colugos).

- Perissodactyla (odd-toed ungulates) are closer to Carnivora and bats than to Artiodactyla (even-toed ungulates).

The grouping together of the Afrotheria has some geological justification. All surviving members of the Afrotheria live in South America or (mainly) Africa. As Pangaea broke up Africa and South America separated from the other continents less than 150M years ago, and from each other between 100M and 80M years ago.[54][55] The earliest known eutherian mammal is Eomaia, from about 125M years ago. So it would not be surprising if the earliest eutherian immigrants into Africa and South America were isolated there and radiated into all the available ecological niches.

Nevertheless these proposals have been controversial. Paleontologists naturally insist that fossil evidence must take priority over deductions from samples of the DNA of modern animals. More surprisingly, these new family trees have been criticised by other molecular phylogeneticists, sometimes quite harshly: [56]

- Mitochondrial DNA's mutation rate in mammals varies from region to region - some parts hardly ever change and some change extremely quickly and even show large variations between individuals within the same species.[57][58]

- Mammalian mitochondrial DNA mutates so fast that it causes a problem called "saturation", where random noise drowns out any information that may be present. If a particular piece of mitochondrial DNA mutates randomly every few million years, it will have changed several times in the 60 to 75M years since the major groups of placental mammals diverged.[59]

Timing of placental evolution

Recent molecular phylogenetic studies suggest that most placental orders diverged about 100M to 85M years ago, but that modern families first appeared in the late Eocene and early Miocene[60]

Some paleontologists object that no placental fossils have been found from before the end of the Cretaceous - for example Maelestes gobiensis, from about 75M years ago, is a eutherian but not a true placental.[61]

Fossils of the earliest members of most modern groups date from the Paleocene, a few date from later and very few from the Cretaceous, before the extinction of the dinosaurs. But some paleontologists, influenced by molecular phylogenetic studies, have used statistical methods to extrapolate backwards from fossils of members of modern groups and concluded that primates arose in the late Cretaceous.[62]

Evolution of mammalian features

Jaws and middle ears

See also Evolution of mammalian auditory ossicles

Hadrocodium, whose fossils date from the early Jurassic, provides the first clear evidence of fully mammalian jaw joints and middle ears, in which the jaw joint is formed by the dentary and squamosal bones while the articular and quadrate move to the middle ear, where they are know as the incus and malleus. Curiously it is usually classified as a member of the mammaliformes rather than a as a true mammal.

It has been suggested that the typical mammalian middle ear evolved twice independently, in monotremes and in therian mammals, but this idea has been disputed.[63]

Milk production (lactation)

It has been suggested that lactation's original function was to keep eggs moist. Much of the argument is based on monotremes (egg-laying mammals):[64][65][66]

- Monotemes do not have nipples but secrete milk from a hairy patch on their bellies.

- During incubation, monotremes' eggs are covered in a sticky substance whose origin is not known. Before the eggs are laid, their shells have only three layers. Afterwards a fourth layer appears, and its composition is different from that of the original three. The sticky substance and the fourth layer may be produced by the mammary glands.

- If so, that may explain why the patches from which monotremes secrete milk are hairy - it is easier to spread moisture and other substances over the egg from a broad, hairy area than from a small, bare nipple.

Hair and fur

The first clear evidence of hair or fur is in fossils of Castorocauda, from 164M years ago in the mid Jurassic.

From 1955 onwards some scientists have interpreted the foramina (passages) in the maxillae (upper jaws) and premaxillae (small bones in front of the maxillae) of cynodonts as channels which supplied blood vessels and nerves to vibrissae (whiskers), and suggested that this was evidence of hair or fur.[67][68] But foramina do not necessarily show that an animal had vibrissae - for example the modern lizard Tupinambis has foramina which are almost identical to those found in the non-mammalian cynodont Thrinaxodon.[69][70]

Erect limbs

The evolution of erect limbs in mammals is incomplete - living and fossil monotremes have sprawling limbs. In fact some scientists think that the parasagittal (non-sprawling) limb posture is a synapomorphy (distinguishing characteristic) of the Boreosphenida, a group which contains the Theria and therefore includes the last common ancestor of modern marsupials and placentals - and therefore that all earlier mammals had sprawling limbs.[71]

Sinodelphys (the earliest known marsupial) and Eomaia (the earliest known eutherian) lived about 125M years ago, so erect limbs must have evolved before then.

Warm-bloodedness

"Warm-bloodedness" is a complex and rather ambiguous term, because it includes some or all of:

- Endothermy, i.e. the ability to generate heat internally rather than via behaviors such as basking or muscular activity.

- Homeothermy, i.e. maintaining a fairly constant body temperature.

- Tachymetabolism, i.e. maintaining a high metabolic rate, particularly when at rest. This requires a fairly high and stable body temperature, since: biochemical processes run about half as fast if an animal's temperature drops by 10°C; most enzymes have an optimum operating temperature and their efficiency drops rapidly outside the preferred range.

Since we can't know much about the internal mechanisms of extinct creatures, most discussion focuses on homeothermy and tachymetabolism.

Modern monotremes have a lower body temperature and more variable metabolic rate than marsupials and placentals.[72] So the main question is when a monotreme-like metabolism evolved in mammals. The evidence found so far suggests Triassic cynodonts may have had fairly high metabolic rates, but is not conclusive.

Respiratory turbinates

Modern mammals have respiratory turbinates, convoluted structures of thin bone in the nasal cavity. These are lined with mucous membranes which warm and moisten inhaled air and extract heat and moisture from exhaled air. An animal with respiratory turbinates can maintain a high rate of breathing without the danger of drying its lungs out, and therefore may have a fast metabolism. Unfortunately these bones are very delicate and therefore have not yet been found in fossils. But rudimentary ridges like those which support respiratory turbinates have been found in Triassic therapsids such as Thrinaxodon and Diademodon, which suggests that they may have had fairly high metabolic rates. [73] [74][75]

Bony secondary palate

Mammals have a secondary bony palate which separates the respiratory passage from the mouth, allowing them to eat and breathe at the same time. Secondary bony palates have been found in the more advanced cynodonts and have been used as evidence of high metabolic rates.[76][77] [78] But some cold-blooded vertebrates have secondary bony palates (crocodilians and some lizards), while birds, which are warm-blooded, do not have them.[79]

Diaphragm

A muscular diaphragm helps mammals to breathe, especially during strenuous activity. For a diaphragm to work, the ribs must not restrict the abdomen, so that expansion of the chest can be compensated for by reduction in the volume of the abdomen and vice versa. The advanced cynodonts have very very mammal-like rib cages, with greatly reduced lumbar ribs. This suggests that these animals had diaphragms, were capable of strenuous activity for fairly long periods and therefore had high metabolic rates.[80][81] On the other hand these mammal-like rib cages may have evolved to increase agility.[82] But the movement of even advanced therapsids was "like a wheelbarrow", with the hindlimbs providing all the thrust while the forelimbs only steered the animal, in other words advanced therapsids were not as agile as either modern mammals or the early dinosaurs.[83] So the idea that the main function of these mammal-like rib cages was to increase agility is doubtful.

Limb posture

The therapsids had sprawling forelimbs and semi-erect hindlimbs.[84][85] This suggests that Carrier's constraint would have made it rather difficult for them to move and breathe at the same time, but not as difficult as it is for animals such as lizards which have completely sprawling limbs.[86] But cynodonts (advanced therapsids) had costal plates which stiffened the rib cage and therefore may have reduced sideways flexing of the trunk while moving, which would have made it a little easier for them to breathe while moving .[87] These facts suggest that advanced therapsids were significantly less active than modern mammals of similar size and therefore may have had slower metabolisms.

Insulation (hair and fur)

Insulation is the "cheapest" way to maintain a fairly constant body temperature. So possession of hair of fur would be good evidence of homeothermy, but would not be such strong evidence of a high metabolic rate.[88] [89]

We have already seen that: the first clear evidence of hair or fur is in fossils of Castorocauda, from 164M years ago in the mid Jurassic; arguments that advanced therapsids had hair are unconvincing.

References

- ^ Mammalia: Overview - Palaeos

- ^ R. Cowen, History of Life, Oxford, Blackwell Science, 2000, p. 432.

- ^ Amniota - Palaeos, su palaeos.org.

- ^ Synapsida: Varanopseidae - Palaeos, su palaeos.com.

- ^ Synapsida overview - Palaeos, su palaeos.com.

- ^ Therapsida - Palaeos, su palaeos.com.

- ^ a b Kermack, The evolution of mammalian characters, Croom Helm, 1984.

- ^

«{{{1}}}»

- ^ Therapsida - Palaeos, su palaeos.com.

- ^ Dinocephalia - Palaeos, su palaeos.com.

- ^ Neotherapsida - Palaeos, su palaeos.com.

- ^ Theriodontia - Paleos, su palaeos.com.

- ^ Cynodontia Overview - Palaeos, su palaeos.com.

- ^ Olenekian Age of the Triassic - Palaeos, su palaeos.com.

- ^ The Triassic Period - Palaeos, su palaeos.com.

- ^ Cynodontia: Overview - Palaeos, su palaeos.com.

- ^ M.E. Raichle, Appraising the brain's energy budget, in PNAS, vol. 99, n. 16, August 6, 2002, pp. 10237-10239.

- ^ Brain power, su newscientist.com, New Scientist, 2006.

- ^ J Travis, Visionary research: scientists delve into the evolution of color vision in primates, in Science News, vol. 164, n. 15, October 2003.

- ^ R.L. Cifelli, Early mammalian radiations, in Journal of Paleontology, November 2001.

- ^ Mammaliformes - Palaeos, su palaeos.com.

- ^ R.L. Cifelli, Early mammalian radiations, in Journal of Paleontology, November 2001.

- ^ Mammaliformes - Palaeos, su palaeos.com.

- ^ Morganucodontids & Docodonts - Palaeos, su palaeos.com.

- ^ Jurassic "Beaver" Found; Rewrites History of Mammals, su news.nationalgeographic.com.

- ^ Symmetrodonta - Palaeos, su palaeos.com.

- ^ Mammalia - Palaeos, su palaeos.com.

- ^ A Jurassic mammal from South America, in Nature, n. 416, 14 March 2002, pp. 165-168, DOI:10.1038/416165a.

- ^ Mammalia - Palaeos, su palaeos.com.

- ^ Appendicular Skeleton, su courses.washington.edu.

- ^ Mammalia: Spalacotheroidea & Cladotheria - Palaeos, su palaeos.com.

- ^ Appendicular Skeleton, su courses.washington.edu.

- ^ Metatheria - Palaeos, su palaeos.com.

- ^ F.S. Szalay, The Mongolian Late Cretaceous Asiatherium, and the early phylogeny and paleobiogeography of Metatheria, in Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, vol. 16, n. 3, 1996, pp. 474-509.

- ^ Oldest Marsupial Fossil Found in China, su news.nationalgeographic.com, National Geographic News, December 15, 2003.

- ^ Didelphimorphia - Palaeos, su palaeos.com.

- ^ Family Peramelidae (bandicoots and echymiperas), su animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu.

- ^ Species is as species does... Part II, su lancelet.blogspot.com.

- ^ Marsupials, su paleo.amnh.org.

- ^ M.J. Novacek, Epipubic bones in eutherian mammals from the late Cretaceous of Mongolia, in Nature, vol. 389, n. 6650, 1997, pp. 440-441.

- ^ White, T.D., An analysis of epipubic bone function in mammals using scaling theory, in Jornal of Theoretical Biology, vol. 139, n. 3, Aug 9 1989, pp. 343-57.

- ^ Eomaia scansoria: discovery of oldest known placental mammal, su evolutionpages.com.

- ^ D Fox, Why we don't lay eggs, 1999.

- ^ Eutheria - Palaeos, su palaeos.com.

- ^ Jurassic "Beaver" Found; Rewrites History of Mammals, su news.nationalgeographic.com.

- ^ Mammaliformes - Palaeos, su palaeos.com.

- ^ Luo, Z.-X., Wible, J.R., A Late Jurassic Digging Mammal and Early Mammal Diversification, in Science, vol. 308, 2005, pp. 103-107..

- ^ Meng, J., Hu, Y., Wang, Y., Wang, X., Li, C., A Mesozoic gliding mammal from northeastern China, in Nature, vol. 444, n. 7121, Dec 2006, pp. 889-893.

- ^ Li, J., Wang, Y., Wang, Y., Li, C., A new family of primitive mammal from the Mesozoic of western Liaoning, China, in Chinese Science Bulletin, vol. 46, n. 9, 2000, pp. 782-785. abstract, in English

- ^ Hu, Y., Meng, J., Wang, Y., Li, C., Large Mesozoic mammals fed on young dinosaurs, in Nature, vol. 433, 2005, pp. 149-152.

- ^ [http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v447/n7147/full/nature05854.html D doi=10.1038/nature05854 Cretaceous eutherians and Laurasian origin for placental mammals near the K/T boundary], in Nature, n. 447, pp. 1003-1006.

- ^ Murphy, W.J., Eizirik, E., Springer, M.S et al, Resolution of the Early Placental Mammal Radiation Using Bayesian Phylogenetics, in Science, vol. 294, n. 5550, 14 December 2001, pp. 2348-2351, DOI: 10.1126/science.1067179.

- ^ Kriegs, J.O., Churakov, G., Kiefmann, M., et al, Retroposed Elements as Archives for the Evolutionary History of Placental Mammals, in PLoS Biol, vol. 4, n. 4, 2006, pp. e91, DOI: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040091. (pdf version)

- ^ Historical perspective (the Dynamic Earth, USGS)

- ^ Cretaceous map

- ^ Insectivora Overviw - Palaeos

- ^ M.S. Springer, Secondary Structure and patterns of evolution among mammalian mitochondrial 12S rRNA molecules, in J. Mol. Evol., vol. 43, 1996, pp. 357-373.

- ^ M.S. Springer, Compensatory substitutions and the evolution of the mitochondrial 12S rRNA gene in mammals, in Mol. Biol. Evol., vol. 12, 1995, pp. 1138-1150.

- ^ W-H Li, Molecular Evolution, Sinauer Associates, 1997.

- ^ O.R.P. Bininda-Emonds, The delayed rise of present-day mammals, in Nature, n. 446, 2007, pp. 507-511.

- ^ Dinosaur Extinction Spurred Rise of Modern Mammals

- ^ R.D. Martin, Primate Origins: Implications of a Cretaceous Ancestry (PDF), in Folia Primatologica, n. 78, 2007, pp. 277-296, DOI:10.1159/000105145. - a similar paper by these authors is free online at New light on the dates of primate origins and divergence

- ^ Independent Origins of Middle Ear Bones in Monotremes and Therians, in Science, vol. 307, n. 5711, 11 February 2005, pp. 910 - 914, DOI:10.1126/science.1105717. For other opinions see "Technical comments" linked from same Web page

- ^ O.T. Oftedal, The mammary gland and its origin during synapsid evolution, in Journal of Mammary Gland Biology and Neoplasia, vol. 7, n. 3, 2002, pp. 225-252.

- ^ O.T. Oftedal, The origin of lactation as a water source for parchment-shelled eggs=Journal of Mammary Gland Biology and Neoplasia, vol. 7, n. 3, 2002, pp. 253-266.

- ^ Lactating on Eggs

- ^ A.S. Brink, A study on the skeleton of Diademodon, in Palaeontologia Africana, vol. 3, 1955, pp. 3-39.

- ^ T.S. Kemp, Mammal-like reptiles and the origin of mammals, London, Academic Press, 1982, p. 363.

- ^ Bennett, A. F. and Ruben, J. A. (1986) "The metabolic and thermoregulatory status of therapsids"; pp. 207-218 in N. Hotton III, P. D. MacLean, J. J. Roth and E. C. Roth (eds), "The ecology and biology of mammal-like reptiles", Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington.

- ^ R. Estes, Cranial anatomy of the cynodont reptile Thrinaxodon liorhinus, in Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology, 1961, pp. 165-180.

- ^ Z. Kielan−Jaworowska, Limb posture in early mammals: Sprawling or parasagittal (PDF), in Acta Palaeontologica Polonica, vol. 51, n. 3, 2006, pp. 10237-10239.

- ^ G.S. Paul, Predatory Dinosaurs of the World, New York, Simon and Schuster, 1988, p. 464.

- ^ W.H. Hillenius, The evolution of nasal turbinates and mammalian endothermy, in Paleobiology, vol. 18, n. 1, 1992, pp. 17-29.

- ^ J. Ruben, The evolution of endothermy in mammals and birds: from physiology to fossils, in Annual Review of Physiology, vol. 57, 1995, pp. 69-95.

- ^ A.S. Brink, A study on the skeleton of Diademodon, in Palaeontologia Africana, vol. 3, 1955, pp. 3-39.

- ^ A.S. Brink, A study on the skeleton of Diademodon, in Palaeontologia Africana, vol. 3, 1955, pp. 3-39.

- ^ T.S. Kemp, Mammal-like reptiles and the origin of mammals, London, Academic Press, 1982, p. 363.

- ^ B.K. McNab, The evolution of endothermy in the phylogeny of mammals, in American Naturalist, vol. 112, 1978, pp. 1-21.

- ^ Bennett, A. F. and Ruben, J. A. (1986) "The metabolic and thermoregulatory status of therapsids"; pp. 207-218 in N. Hotton III, P. D. MacLean, J. J. Roth and E. C. Roth (eds), "The ecology and biology of mammal-like reptiles", Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington.

- ^ A.S. Brink, A study on the skeleton of Diademodon, in Palaeontologia Africana, vol. 3, 1955, pp. 3-39.

- ^ T.S. Kemp, Mammal-like reptiles and the origin of mammals, London, Academic Press, 1982, p. 363.

- ^ Bennett, A. F. and Ruben, J. A. (1986) "The metabolic and thermoregulatory status of therapsids"; pp. 207-218 in N. Hotton III, P. D. MacLean, J. J. Roth and E. C. Roth (eds), "The ecology and biology of mammal-like reptiles", Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington.

- ^ R. Ccowen, History of Life, Oxford, Blackwell Science, 2000, p. 432.

- ^ F.A., Jr Jenkins, The postcranial skeleton of African cynodonts, in Bulletin of the Peabody Museum of Natural History, n. 36, 1971, pp. 1-216.

- ^ T.S. Kemp, Mammal-like reptiles and the origin of mammals, London, Academic Press, 1982, p. 363.

- ^ F.H Pough, Vertebrate Life, New Jersey, Prentice-Hall, 1996, p. 798.

- ^ C.A. Sidor, Ghost lineages and "mammalness": assessing the temporal pattern of character acquisition in the Synapsida, in Paleobiology, n. 24, 1998, pp. 254-273.

- ^ K. Schmidt-Nielsen, Animal physiology: Adaptation and environment, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1975, p. 699.

- ^ P.C. Withers, Comparative Animal Physiology, Fort Worth, Saunders College, 1992, p. 949.

External links

- The Cynodontia covers several aspects of the evolution of cynodonts into mammals, with plenty of references.