Negazione del riscaldamento globale: differenze tra le versioni

| Riga 61: | Riga 61: | ||

Nel 1998 Gelbspan commentò che i suoi colleghi giornalisti accettavano che stesse avvenendo il riscaldamento globale, ma disse che si trovavano nella "negazione 'stadio due' della "[[crisi climatica]]"', incapaci di accettare la fattibilità di risposte al problema.<ref>{{cita|Gelbspan|1998| pp=3, 35, 46, 197}}</ref> Un libro successivo di Milburn e Conrad su ''The Politics of Denial'' ("la politica della negazione") descriveva "forze economiche e psicologiche" che producevano negazione del consenso sui temi del riscaldamento del globale.<ref name="MilburnConrad1998">{{cita libro|cognome1=Milburn|nome1=Michael A.|cognome2=Conrad|nome2=Sheree D.|titolo=The Politics of Denial|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ntVE1n3g51wC&pg=PA216|anno= 1998|editore=MIT Press|citazione=Here again, as in the case of ozone depletion, economic and psychological forces are operating to produce a level of denial that threatens future generations.|isbn=978-0-262-63184-6|pp=216–|accesso=12 luglio 2015|dataarchivio=22 marzo 2021|urlarchivio=https://web.archive.org/web/20210322153353/https://books.google.com/books?id=ntVE1n3g51wC&pg=PA216|urlmorto=no}}</ref> |

Nel 1998 Gelbspan commentò che i suoi colleghi giornalisti accettavano che stesse avvenendo il riscaldamento globale, ma disse che si trovavano nella "negazione 'stadio due' della "[[crisi climatica]]"', incapaci di accettare la fattibilità di risposte al problema.<ref>{{cita|Gelbspan|1998| pp=3, 35, 46, 197}}</ref> Un libro successivo di Milburn e Conrad su ''The Politics of Denial'' ("la politica della negazione") descriveva "forze economiche e psicologiche" che producevano negazione del consenso sui temi del riscaldamento del globale.<ref name="MilburnConrad1998">{{cita libro|cognome1=Milburn|nome1=Michael A.|cognome2=Conrad|nome2=Sheree D.|titolo=The Politics of Denial|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ntVE1n3g51wC&pg=PA216|anno= 1998|editore=MIT Press|citazione=Here again, as in the case of ozone depletion, economic and psychological forces are operating to produce a level of denial that threatens future generations.|isbn=978-0-262-63184-6|pp=216–|accesso=12 luglio 2015|dataarchivio=22 marzo 2021|urlarchivio=https://web.archive.org/web/20210322153353/https://books.google.com/books?id=ntVE1n3g51wC&pg=PA216|urlmorto=no}}</ref> |

||

Questi tentativi da parte di gruppi di negazione del cambiamento climatico furono riconosciuti come una campagna organizzata che iniziava negli anni 2000.<ref>{{cita|Painter, Ashe, 2012}}: "Academics took note of the discourse when they began to analyse media representations of climate change knowledge and its effect on public perceptions and policy-making, but in the 1990s, they did not yet focus on it as a coherent and defined phenomenon. This changed in the 2000s when McCright and Dunlap played an important role in deepening the concept of climate skepticism."</ref> I sociologi [[Riley Dunlap]] e [[Aaron McCright]] giocarono un ruolo significativo in questo mutamento quando nel 2000 pubblicarono un articolo che esplorava le connessioni tra i think-tank conservatori e la negazione del cambiamento climatico.<ref>{{cita|Painter, Ashe, 2012}}:"McCright and Dunlap played an important role in deepening the concept of climate skepticism. Examining what they termed a 'conservative countermovement' to undermine climate change policy ... McCright and Dunlap went beyond the study of media representations of climate change knowledge to give a coherent picture of the movement behind climate skepticism in the US."</ref> Un lavoro successivo avrebbe |

Questi tentativi da parte di gruppi di negazione del cambiamento climatico furono riconosciuti come una campagna organizzata che iniziava negli anni 2000.<ref>{{cita|Painter, Ashe, 2012}}: "Academics took note of the discourse when they began to analyse media representations of climate change knowledge and its effect on public perceptions and policy-making, but in the 1990s, they did not yet focus on it as a coherent and defined phenomenon. This changed in the 2000s when McCright and Dunlap played an important role in deepening the concept of climate skepticism."</ref> I sociologi [[Riley Dunlap]] e [[Aaron McCright]] giocarono un ruolo significativo in questo mutamento quando nel 2000 pubblicarono un articolo che esplorava le connessioni tra i think-tank conservatori e la negazione del cambiamento climatico.<ref>{{cita|Painter, Ashe, 2012}}:"McCright and Dunlap played an important role in deepening the concept of climate skepticism. Examining what they termed a 'conservative countermovement' to undermine climate change policy ... McCright and Dunlap went beyond the study of media representations of climate change knowledge to give a coherent picture of the movement behind climate skepticism in the US."</ref> Un lavoro successivo avrebbe sviluppato l'osservazione che gruppi specifici stavano incoraggiando lo scetticismo contro il cambiamento climatico — uno studio del 2008 della University of Central Florida analizzò le fonti della letteratura "ambientalmente scettica" pubblicata negli Stati Uniti. L'analisi dimostrò che il 92% della letteratura era in tutto o in parte associato a sedicenti think-tank conservatori.<ref>{{cita|Jacques, Dunlap, Freeman, 2008 pp. 349–385}}</ref> Poi nel 2015 una ricerca identificò {{formatnum:4556}} soggetti con legami di reti sovrapposte a 164 organizzazioni che sono responsabili della maggior parte dei tentativi di sminuire la minaccia i cambiamento climatico negli USA.<ref name="Eric Roston">{{cita web|url=https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-11-30/unearthing-america-s-deep-network-of-climate-change-deniers|titolo=Unearthing America's Deep Network of Climate Change Deniers|autore=Eric Roston|sito=[[Bloomberg News]]|data= 30 novembre 2015|accesso=6 marzo 2017|dataarchivio=10 novembre 2021|urlarchivio=https://web.archive.org/web/20211110011740/https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-11-30/unearthing-america-s-deep-network-of-climate-change-deniers|urlmorto=no}}</ref><ref name="Justin Farrell">{{cita testo |cognome=Farrell|nome=Justin|s2cid=18207833|anno=2015|titolo=Network structure and influence of the climate change counter-movement|rivista=[[Nature Climate Change]] |volume=6 |numero=4 |pp=370–374 |bibcode=2016NatCC...6..370F |doi=10.1038/nclimate2875 }}</ref> |

||

{{Clear}} |

{{Clear}} |

||

Versione delle 14:30, 18 lug 2023

La negazione del riscaldamento globale (o del cambiamento climatico) è la negazione o il dubbio ingiustificato che contraddice il consenso scientifico sul riscaldamento globale.

I fautori della negazione usano comunemente tattiche retoriche per far apparire una controversia scientifica dove in realtà non sussiste.[6][7][8] Molti tra i negazionisti climatici si dichiarano "scettici sul riscaldamento globale",[9][10] il che è una descrizione impropria.[11][12][13]

La negazione del riscaldamento globale comprende dubbi sulla misura in cui il cambiamento climatico sia causato dagli esseri umani, i suoi effetti su natura e società, e il potenziale di adattamento al riscaldamento globale nelle azioni umane.[10][14][15] In misura minore, la negazione del riscaldamento globale è implicita quando le persone accettano la scienza, ma non riescono a conciliarla con le loro credenze o azioni (dissonanza cognitiva).[16] Alcuni studi di scienze sociali hanno analizzato queste posizioni come forme di negazionismo,[17][18] pseudoscienza,[19] o propaganda.[20]

La cospirazione per inficiare la fiducia del pubblico nella scienza climatica è organizzata da interessi industriali, politici e e ideologici.[21][22] La negazione del riscaldamento globale è stata associata alla lobby dell'energia, ai fratelli Koch (Charles Koch e David Koch), a sostenitori dell'industria, think tank conservatori e organi di informazione "alternativi" di destra, spesso statunitensi.[20][23][24][25] Più del 90% dei saggi scettici sul cambiamento climatico provengono da think-tank di destra.[26] La negazione del riscaldamento globale sta vanificando i tentativi di mitigazione climatica, ed esercita una potente influenza sulle politiche del cambiamento climatico e sull'artificiosa controversia sul riscaldamento globale.[27][28]

Negli anni 1970 le compagnie petrolifere pubblicarono una finta ricerca scientifica che concordava largamente con la concezione della comunità scientifica sul riscaldamento globale. Da allora, per decenni, le compagnie petrolifere hanno organizzato un'ampia e sistematica campagna di negazione del cambiamento climatico per seminare pubblica disinformazione, una strategia che mostra affinità con l'elaborata negazione dei rischi da tabagismo animata dall'industria del tabacco.[29] Alcune campagne furono addirittura svolte dagli stessi soggetti che in precedenza avevano diffuso la campagna negazionista dell'industria del tabacco.[30][31][32]

Terminologia

"Scetticismo sul cambiamento climatico" e "negazione del cambiamento climatico" si riferiscono a negazione, sottovalutazione o dubbio ingiustificato riguardo il consenso scientifico su stima e portata del riscaldamento globale, suo significato, o sua connessione al comportamento umano, in tutto o in parte.[33][34]

Benché esista una distinzione tra scetticismo, che significa dubitare della verità di un'asserzione, e la franca negazione della verità di un'asserzione, nel dibattito pubblico frasi come "scetticismo climatico" sono state spesso usate come sinonimo di negazionismo climatico o "contrarismo".[35][36]

La terminologia emerse negli anni 1990. Anche se tutti gli scienziati aderiscono allo scetticismo scientifico come parte necessaria del processo, da metà novembre 1995 la parola "scettico" fu usata specificamente per la minoranza che diffondeva concezioni contrarie al consenso scientifico. Questo piccolo gruppo di scienziati presentava le proprie posizioni in dichiarazioni pubbliche agli organi di informazione, piuttosto che alla comunità scientifica.[37][38] Questa abitudine continuò.[39] Nel suo articolo del 1995 "The Heat is On: The warming of the world's climate sparks a blaze of denial", Ross Gelbspan disse che l'industria aveva assoldato "una piccola banda di scettici" per confondere l'opinione pubblica con una "persistente e ben finanziata campagna di negazione".[40] Il suo libro del 1997 The Heat is On potrebbe essere il primo che si concentra specificamente sull'argomento.[41] In esso, Gelbspan discusse una "negazione pervasiva del riscaldamento globale" in una "campagna persistente di negazione e dissimulazione" implicante "finanziamenti non rivelati di questi 'scettici dell'effetto serra' " con "gli scettici del clima" che confondono l'opinione pubblica e influenzano i decisori politici.[42]

Un documentario del 2006 per CBC Television sulla campagna si intitolava The Denial Machine.[43][44] Nel 2007 la giornalista Sharon Begley scrisse a proposito della "macchina della negazione",[45] una frase successivamente usata dagli studiosi.[21][44]

In aggiunta alla negazione esplicita, alcuni gruppi sociali hanno dimostrato negazione implicita accettando il consenso scientifico, ma non riuscendo a "tradurre l'accettazione in azione".[16] Questo fu esemplificato dallo studio di Kari Norgaard su un villaggio in Norvegia colpito dal cambiamento climatico, i cui residenti si interessavano piuttosto di altri problemi.[46]

La terminologia non è pacifica: la maggior parte di coloro che respingono il consenso scientifico usano i termini "scettico" e "scetticismo sul cambiamento climatico", e solo pochi hanno preferito essere descritti come negatori,[12][34] ma la parola scetticismo è usata scorrettamente, dato che lo scetticismo scientifico è parte intrinseca della metodologia scientifica.[13][47][48] Il termine "contrario" è più specifico, ma usato meno frequentemente. In letteratura e giornalismo scientifici, I termini "negazione del cambiamento climatico" e "negatori del cambiamento climatico" hanno un uso ben radicato come termini descrittivi senza alcun intento peggiorativo.[49] Sia il National Center for Science Education sia lo storico Spencer R. Weart riconoscono che entrambe le opzioni sono problematiche, ma hanno deciso di usare "negazione del cambiamento climatico" piuttosto che "scetticismo".[49][50]

I termini legati al "negazionismo" sono stati criticati in quanto introdurrebbero un tono moralistico, e potenzialmente implicherebbero un nesso con il negazionismo dell'Olocausto.[13][51] Secondo alcune insinuazioni, fermamente contestate dal mondo accademico, tale accostamento sarebbe deliberato.[52] L'uso di "negazione" è assai anteriore all'Olocausto, ed è comunemente applicato in altri ambiti come il negazionismo dell'HIV/AIDS: John Timmer di Ars Technica ha osservato che questo tipo di insinuazione rappresenta già intrinsecamente una forma di negazione.[53]

Nel 2014 una lettera aperta del Committee for Skeptical Inquiry invitò gli organi di informazione a smettere di usare il termine "scetticismo" quando ci si riferisca alla negazione del cambiamento climatico. Veniva contrapposto lo scetticismo scientifico — che è "basilare per il metodo scientifico" — con la negazione — "il rigetto a priori di idee senza [esprimere] considerazioni obiettive" — e il comportamento di soggetti implicati nel tentativo di screditare la scienza climatica. Vi si diceva "Non tutti i soggetti che si definiscono scettici sul cambiamento climatico sono negatori. Ma praticamente tutti i negatori si sono falsamente auto-etichettati come scettici. Continuando ad utilizzare questo termine improprio, i giornalisti hanno attribuito immeritata credibilità a quanti rifiutano scienza e indagine scientifica."[52][54] Nel giugno 2015 a Media Matters for America fu segnalato dal public editor[55] del New York Times che tale testata tendeva sempre più ad usare "negatore" quando "qualcuno sta mettendo in discussione la scienza consolidata", ma esprimendo questa valutazione in modo soggettivo e senza direttive prestabilite, e non avrebbe usato il termine quando qualcuno è "un po' indeciso sull'argomento o nel mezzo". La direttrice esecutiva di Society of Environmental Journalists disse che seppure c'era ragionevole scetticismo su alcuni temi specifici, riteneva che negatore fosse "il termine più preciso quando qualcuno sostiene che non esista qualcosa come il riscaldamento globale, o è d'accordo che esista ma nega che esso abbia qualche causa a noi comprensibile o qualsiasi impatto che possiamo misurare."[56]

La lettera del Committee for Skeptical Inquiry ispirò una petizione su climatetruth.org[57] in cui ai sottoscrittori veniva chiesto di "Dire all'Associated Press: Stabilite una regola nell'AP Stylebook che vieti l'uso di 'scettico' per descrivere quelli che negano i dati scientifici." Il 22 settembre 2015 l'Associated Press annunciò "un'aggiunta alla voce di AP Stylebook sul riscaldamento globale" che raccomandava, "per descrivere quelli che non accettano la scienza del clima o mettono in discussione che il mondo si stia riscaldando per cause legate all'uomo, usate dubitatori del cambiamento climatico o quelli che respingono la prevalente scienza del clima. Evitate l'uso di scettici o negatori."[58][59] Il 17 maggio 2019 anche The Guardian ripudiò l'uso del termine "scettici del clima" in favore di "negatori della scienza del clima".[60]

Storia

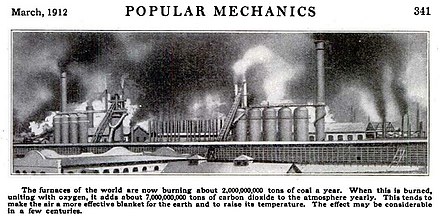

La ricerca sugli effetti sul clima dell'anidride carbonica iniziò nel 1824, quando Joseph Fourier inferì l'esistenza dell'"effetto serra" atmosferico. Nel 1860 John Tyndall quantificò gli effetti dei gas serra sull'assorbimento della radiazione infrarossa. Svante Arrhenius nel 1896 dimostrò che la combustione del carbone poteva causare il riscaldamento globale, e nel 1938 Guy Stewart Callendar trovò che ciò stava già avvenendo in qualche misura.[61][62] La ricerca avanzò rapidamente dopo il 1940; dal 1957 Roger Revelle avvertì l'opinione pubblica sui rischi che la combustione del carbone fosse "un grandioso esperimento scientifico" sul clima.[63][64] NASA e NOAA proseguirono la ricerca, il Charney Report del 1979 concluse che il rilevante riscaldamento era già in atto, e "Una politica aspetta-e-vedi può significare attendere finché è troppo tardi."[65][66]

Nel 1959 uno scienziato che lavorava per la Shell suggerì in un articolo di New Scientist che i cicli del carbone sono troppo vasti per turbare l'equilibrio della natura.[67] Nel 1966 però, un'organizzazione di ricerca dell'industria carbonifera, Bituminous Coal Research Inc., pubblicò la sua risultanza secondo cui se le tendenze prevalenti nel consumo di carbone continuano, "la temperatura dell'atmosfera terrestre crescerà e ne deriveranno vasti cambiamenti nei climi della terra." "Questi cambiamenti di temperatura causeranno lo scioglimento delle calotte polari che, a loro volta, provocheranno l'inondazione di molte città costiere, tra cui New York e Londra."[68] In una discussione seguente questo studio nella medesima pubblicazione, un tecnico della combustione di Peabody Coal, ora Peabody Energy, il più grande fornitore di carbone al mondo, aggiunse che l'industria carbonifera stava meramente "guadagnando tempo" prima che fossero promulgate norme statali ulteriori sull'inquinamento dell'aria, per migliorarne la pulizia. Nondimeno, l'industria carbonifera per decenni successivi propugnò pubblicamente la posizione che un aumento del diossido di carbonio fosse vantaggioso per il pianeta.[68]

In risposta alla crescente presa di coscienza nella pubblica opinione circa l'effetto serra negli anni 1970, si mobilitò la reazione conservatrice, confutando le preoccupazioni ambientali che avrebbero portato a normative del governo. Nel 1977 il Segretario all'Energia, il repubblicano James Schlesinger, consigliò al presidente (democratico)[69] Jimmy Carter di non prendere provvedimenti circa un memorandum in tema di cambiamento climatico, adducendo l'incertezza.[70] Durante la presidenza di Ronald Reagan (1981) il riscaldamento globale divenne un tema politico, con immediati progetti di tagliare le spese sulla ricerca ambientale — specie se collegata al clima — e di smettere di finanziare il monitoraggio della CO2. Reagan nominò Segretario dell'energia degli Stati Uniti d'America James B. Edwards, secondo cui non esisteva alcun vero problema di riscaldamento globale. Il parlamentare Al Gore aveva studiato sotto la guida di Revelle e conosceva gli sviluppi scientifici: si unì ad altri che organizzavano audizioni al Congresso dal 1981 in poi, con testimonianze di scienziati tra cui Revelle, Stephen Schneider e Wallace Smith Broecker. Le audizioni sensibilizzarono l'opinione pubblica a sufficienza per ridurre i tagli alla ricerca sull'atmosfera.[71] Si sviluppò un dibattito polarizzato dalle posizioni dei partiti politici. Nel 1982 Sherwood B. Idso pubblicò il libro Carbon Dioxide: Friend or Foe? che diceva che gli aumenti di CO2 non avrebbero danneggiato il pianeta, ma avrebbero fertilizzato i raccolti ed erano "qualcosa che andava incoraggiato e non represso", al contempo lamentando che le sue teorie fossero state respinte dall'"establishment scientifico". Un rapporto della Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) dichiarò che il riscaldamento globale era "non un problema teorico ma una minaccia i cui effetti si sarebbero sentiti entro pochi anni", con conseguenze potenzialmente "catastrofiche".[72] L'amministrazione Reagan reagì chiamando "allarmista" il rapporto, e la diatriba ebbe ampia risonanza mediatica. L'attenzione dell'opinione pubblica si rivolse ad altri argomenti, poi nel 1985 la scoperta del buco nell'ozono polare determinò una rapida reazione internazionale. Per l'opinione pubblica, ciò era legato al cambiamento climatico e alla possibilità di un'azione efficace, ma l'interesse per la notizia si attenuò.[73]

L'attenzione dell'opinione pubblica riprese vigore in relazione alle siccità estive e alle ondate di calore, quando James Hansen intervenne all'audizione del Congresso del 23 giugno 1988,[74][75] affermando con elevata sicurezza che è in corso un riscaldamento a lungo termine, con la probabilità di un forte riscaldamento nei prossimi 50 anni, e mettendo in guardia da probabili tempeste e inondazioni. Aumentò anche l'attenzione degli organi di informazione: la comunità scientifica aveva raggiunto un ampio consenso sul fatto che il clima stava cambiando, l'attività umana ne era molto probabilmente la causa principale, e che ci sarebbero state conseguenze significative se la tendenza al riscaldamento non fosse stata raffrenata.[76] Questi fatti incoraggiarono il dibattito su nuove leggi riguardanti normative ambientali, il che era osteggiato dall'industria dei combustibili fossili.[77]

A partire dal 1989, organizzazioni finanziate dalle industrie, tra cui Global Climate Coalition e George C. Marshall Institute, cercarono di suscitare dubbi nell'opinione pubblica, riproponendo la strategia sviluppata dall'industria del tabacco.[78][79][80] Un piccolo gruppo di scienziati non allineati al consenso sul riscaldamento globale prese un impegno politico, e, con l'appoggio di interessi politici conservatori, iniziò a pubblicare mediante libri e stampa generica invece che sulle riviste scientifiche.[81] Nel gruppetto di studiosi figuravano pure alcuni soggetti che avevano partecipato alla strategia "dubitativa" dell'industria del tabacco.[82] Spencer Weart afferma che proprio in questo periodo il legittimo scetticismo su aspetti elementari della scienza climatica non era più giustificabile, e quelli che diffondevano sfiducia su questi argomenti divennero negatori.[83] Poiché i loro argomenti venivano sempre più respinti dalla comunità scientifica e dai nuovi dati, i negatori ricorsero ad argomentazioni politiche, portando attacchi personali alla reputazione degli scienziati, e promuovendo l'idea di una cospirazione del riscaldamento globale.[84]

Con la caduta del comunismo nel 1989 e la diffusione internazionale del movimento ambientale al summit della Terra (Rio de Janeiro 1992), l'attenzione dei think-tank conservatori USA, che erano stati organizzati negli anni 1970 come un contro-movimento intellettuale verso il socialismo, virò dalla "paura rossa" alla "paura verde" che i conservatori vedevano come una minaccia alle loro mire di proprietà privata, economie di mercato fondate sul libero commercio e capitalismo globale. In quanto contro-movimento, usavano lo scetticismo ambientale per promuovere la negazione della realtà di problemi come perdita di biodiversità e cambiamento climatico.[85]

Nel 1992 un rapporto EPA mise in relazione il fumo passivo con il cancro ai polmoni. L'industria del tabacco si rivolse all'impresa di pubbliche relazioni APCO Worldwide, che predispose una strategia di campagne astroturfing finalizzate a mettere in dubbio la scienza, collegando l'ansia di fumare ad altri problemi, compreso il riscaldamento climatico, così da orientare l'opinione pubblica contro gli appelli all'intervento del governo. La campagna raffigurava le preoccupazioni del pubblico come "timori infondati" asseritamente basati solo su "scienza spazzatura" contrapposta alla loro "scienza sana" e agiva attraverso gruppi di facciata, soprattutto l'Advancement of Sound Science Center (TASSC) e il suo sito Junk Science, gestito da Steven Milloy. Una nota dell'industria del tabacco commentava "Il dubbio è il prodotto che fa per noi perché è il miglior mezzo per competere con l'"insieme di prove" che esiste nella mente del grande pubblico. È anche il mezzo per creare una controversia." Negli anni 1990 si spense la campagna del tabacco, e il TASSC iniziò a ricevere finanziamenti da compagnie petrolifere tra cui la Exxon. Il suo sito assunse un ruolo centrale nel diffondere "quasi ogni tipo di negazione del cambiamento climatico che ha raggiunto la stampa di massa."[86]

Negli anni 1990 il Marshall Institute iniziò una campagna contro la maggior regolazione normativa di aspetti ambientali quali pioggia acida, buco nell'ozono, fumo passivo, e la pericolosità del DDT.[79][86][82] In ciascun caso il loro argomento era che la scienza era troppo incerta per giustificare un intervento del governo; una strategia ricalcata su precedenti tentativi di sminuire gli effetti sulla salute del tabacco negli anni 1980.[78][80] Questa campagna sarebbe continuata nei vent'anni successivi.[87]

Queste iniziative riuscirono ad influenzare nel grande pubblico la percezione del cambiamento climatico.[88] Tra il 1988 e gli anni 1990 il dibattito pubblico si spostò, da scienza e dati sul cambiamento climatico, a discussioni di politica e controversie di contorno.[89]

La campagna per diffondere dubbio continuò negli anni 1990, anche con un'azione pubblicitaria finanziata da paladini dell'industria carbonifera, tendente a "riposizionare il riscaldamento globale come una teoria piuttosto che un dato di fatto",[90][91] e una proposta del 1988 dell'American Petroleum Institute per reclutare scienziati che convincessero politici, organi di informazione e opinione pubblica che la scienza climatica era troppo incerta per fornire la motivazione di normative ambientali.[92] La proposta comprendeva una strategia in più punti da 5 milioni di dollari per "massimizzare l'impatto delle opinioni scientifiche coerenti con le nostre sul Congresso, sugli organi di informazione e su altri interlocutori chiave", con l'obiettivo di "sollevare dubbi e sminuire la cultura scientifica prevalente".[93]

Nel 1998 Gelbspan commentò che i suoi colleghi giornalisti accettavano che stesse avvenendo il riscaldamento globale, ma disse che si trovavano nella "negazione 'stadio due' della "crisi climatica"', incapaci di accettare la fattibilità di risposte al problema.[94] Un libro successivo di Milburn e Conrad su The Politics of Denial ("la politica della negazione") descriveva "forze economiche e psicologiche" che producevano negazione del consenso sui temi del riscaldamento del globale.[95]

Questi tentativi da parte di gruppi di negazione del cambiamento climatico furono riconosciuti come una campagna organizzata che iniziava negli anni 2000.[96] I sociologi Riley Dunlap e Aaron McCright giocarono un ruolo significativo in questo mutamento quando nel 2000 pubblicarono un articolo che esplorava le connessioni tra i think-tank conservatori e la negazione del cambiamento climatico.[97] Un lavoro successivo avrebbe sviluppato l'osservazione che gruppi specifici stavano incoraggiando lo scetticismo contro il cambiamento climatico — uno studio del 2008 della University of Central Florida analizzò le fonti della letteratura "ambientalmente scettica" pubblicata negli Stati Uniti. L'analisi dimostrò che il 92% della letteratura era in tutto o in parte associato a sedicenti think-tank conservatori.[98] Poi nel 2015 una ricerca identificò 4 556 soggetti con legami di reti sovrapposte a 164 organizzazioni che sono responsabili della maggior parte dei tentativi di sminuire la minaccia i cambiamento climatico negli USA.[99][100]

Note

- ^ (EN) John Cook, Quantifying the consensus on anthropogenic global warming in the scientific literature, in Environmental Research Letters, vol. 8, n. 2, 15 maggio 2013, pp. 024024, Bibcode:2013ERL.....8b4024C, DOI:10.1088/1748-9326/8/2/024024.«there is a significant gap between public perception and reality, with 57% of the US public either disagreeing or unaware that scientists overwhelmingly agree that the earth is warming due to human activity (Pew 2012). Contributing to this "consensus gap" are campaigns designed to confuse the public about the level of agreement among climate scientists. ... The narrative presented by some dissenters is that the scientific consensus is "on the point of collapse" while "the number of scientific 'heretics' is growing with each passing year" A systematic, comprehensive review of the literature provides quantitative evidence countering this assertion. The number of papers rejecting AGW is a minuscule proportion of the published research, with the percentage slightly decreasing over time. Among papers expressing a position on AGW, an overwhelming percentage (97.2% based on self-ratings, 97.1% based on abstract ratings) endorses the scientific consensus on AGW.»

- ^ John Cook, Naomi Oreskes, Peter T. Doran, William R. L. Anderegg, Bart Verheggen, Consensus on consensus: a synthesis of consensus estimates on human-caused global warming, in Environmental Research Letters, vol. 11, n. 4, 2016, p. 048002, Bibcode:2016ERL....11d8002C, DOI:10.1088/1748-9326/11/4/048002.

- ^ (EN) James L. Powell, Scientists Reach 100% Consensus on Anthropogenic Global Warming, in Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society, vol. 37, n. 4, 20 novembre 2019, pp. 183–184, DOI:10.1177/0270467619886266. URL consultato il 15 novembre 2020.

- ^ (EN) Mark Lynas, Benjamin Z. Houlton e Simon Perry, Greater than 99% consensus on human caused climate change in the peer-reviewed scientific literature, in Environmental Research Letters, vol. 16, n. 11, 19 ottobre 2021, p. 114005, Bibcode:2021ERL....16k4005L, DOI:10.1088/1748-9326/ac2966.

- ^ (EN) Krista F. Myers, Peter T. Doran, John Cook, John E. Kotcher e Teresa A. Myers, Consensus revisited: quantifying scientific agreement on climate change and climate expertise among Earth scientists 10 years later, in Environmental Research Letters, vol. 16, n. 10, 20 ottobre 2021, p. 104030, Bibcode:2021ERL....16j4030M, DOI:10.1088/1748-9326/ac2774.

- ^ (EN) Mark Hoofnagle e Chris Hoofnagle, denialism blog : About, su ScienceBlogs, 8 settembre 2007. URL consultato il 7 febbraio 2022 (archiviato dall'url originale l'8 settembre 2007).«Denialism is the employment of rhetorical tactics to give the appearance of argument or legitimate debate, when in actuality there is none. These false arguments are used when one has few or no facts to support one's viewpoint against a scientific consensus or against overwhelming evidence to the contrary. They are effective in distracting from actual useful debate using emotionally appealing, but ultimately empty and illogical assertions. .... 5 general tactics are used by denialists to sow confusion. They are conspiracy, selectivity (cherry-picking), fake experts, impossible expectations (also known as moving goalposts), and general fallacies of logic.»

- ^ (EN) Pascal Diethelm e Martin McKee, Denialism: what is it and how should scientists respond?, in European Journal of Public Health, vol. 19, n. 1, gennaio 2009, pp. 2–4, DOI:10.1093/eurpub/ckn139, PMID 19158101.

- ^ (EN) G.T. Farmer e John Cook, Climate Change Science: A Modern Synthesis: Volume 1 – The Physical Climate, collana Climate Change Science: A Modern Synthesis, Springer Netherlands, 2013, pp. 449–450, ISBN 978-94-007-5757-8. URL consultato il 7 febbraio 2022.

- ^ (EN) Paul Matthews, Why Are People Skeptical about Climate Change? Some Insights from Blog Comments, in Environmental Communication, vol. 9, n. 2, 3 aprile 2015, pp. 153–168, DOI:10.1080/17524032.2014.999694, ISSN 1752-4032.

- ^ a b National Center for Science Education, 2016.

- ^ (EN) Karin Edvardsson Björnberg et al., Climate and environmental science denial: A review of the scientific literature published in 1990–2015, in Journal of Cleaner Production, vol. 167, 2017, pp. 229–241, DOI:10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.08.066.

- ^ a b Washington, 2013, p. 2: "Many climate change deniers call themselves climate 'skeptics' ... However, refusing to accept the overwhelming 'preponderance of evidence' is not skepticism, it is denial and should be called by its true name ... The use of the term 'climate skeptic' is a distortion of reality ... Skepticism is healthy in both science and society; denial is not."

- ^ a b c (EN) Saffron J. O'Neill, Max Boykoff, Climate denier, skeptic, or contrarian?, in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 107, n. 39, 28 settembre 2010, pp. E151, Bibcode:2010PNAS..107E.151O, DOI:10.1073/pnas.1010507107, ISSN 0027-8424, PMC 2947866, PMID 20807754.«Using the language of denialism brings a moralistic tone into the climate change debate that we would do well to avoid. Further, labeling views as denialist has the potential to inappropriately link such views with Holocaust denial ... However, skepticism forms an integral part of the scientific method and thus the term is frequently misapplied in such phrases as "climate change skeptic".»

- ^ (EN) National Center for Science Education, Climate change is good science, su ncse.com, National Center for Science Education, 4 giugno 2010. URL consultato il 21 giugno 2015 (archiviato il 24 aprile 2016). "The first pillar of climate change denial—that climate change is bad science—attacks various aspects of the scientific consensus about climate change ... there are climate change deniers:

- who deny that significant climate change is occurring

- who ... deny that human activity is significantly responsible

- who ... deny the scientific evidence about its significant effects on the world and our society ...

- who ... deny that humans can take significant actions to reduce or mitigate its impact.

- ^ Powell, 2012, pp. 170–173: "Anatomy of Denial—Global warming deniers ... . throw up a succession of claims, and fall back from one line of defense to the next as scientists refute each one in turn. Then they start over:

'The earth is not warming.'

'All right, it is warming but the Sun is the cause.'

'Well then, humans are the cause, but it doesn't matter, because it warming will do no harm. More carbon dioxide will actually be beneficial. More crops will grow.'

'Admittedly, global warming could turn out to be harmful, but we can do nothing about it.'

'Sure, we could do something about global warming, but the cost would be too great. We have more pressing problems here and now, like AIDS and poverty.'

'We might be able to afford to do something to address global warming some-day, but we need to wait for sound science, new technologies, and geoengineering.'

'The earth is not warming. Global warming ended in 1998; it was never a crisis.' - ^ a b National Center for Science Education, 2016: "Climate change denial is most conspicuous when it is explicit, as it is in controversies over climate education. The idea of implicit (or "implicatory") denial, however, is increasingly discussed among those who study the controversies over climate change. Implicit denial occurs when people who accept the scientific community's consensus on the answers to the central questions of climate change on the intellectual level fail to come to terms with it or to translate their acceptance into action. Such people are in denial, so to speak, about climate change."

- ^ Dunlap, 2013, pp. 691–698: "There is debate over which term is most appropriate ... Those involved in challenging climate science label themselves 'skeptics' ... Yet skepticism is ... a common characteristic of scientists, making it inappropriate to allow those who deny AGW to don the mantle of skeptics ... It seems best to think of skepticism-denial as a continuum, with some individuals (and interest groups) holding a skeptical view of AGW ... and others in complete denial"

- ^ Timmer, 2014

- ^ (EN) Sven Ove Hansson, Science denial as a form of pseudoscience, in Studies in History and Philosophy of Science, vol. 63, 2017, pp. 39–47, Bibcode:2017SHPSA..63...39H, DOI:10.1016/j.shpsa.2017.05.002, PMID 28629651.

- ^ a b Jacques Dunlap Freeman, 2008, p. 351: "Conservative think tanks ... and their backers launched a full-scale counter-movement ... We suggest that this counter-movement has been central to the reversal of US support for environmental protection, both domestically and internationally. Its major tactic has been disputing the seriousness of environmental problems and undermining environmental science by promoting what we term 'environmental scepticism.'"

- ^ a b Dunlap, 2013, pp. 691–698: "From the outset, there has been an organized 'disinformation' campaign ... to 'manufacture uncertainty' over AGW ... especially by attacking climate science and scientists ... waged by a loose coalition of industrial (especially fossil fuels) interests and conservative foundations and think tanks ... often assisted by a small number of contrarian scientists. ... greatly aided by conservative media and politicians . and more recently by a bevy of skeptical bloggers. This 'denial machine' has played a crucial role in generating skepticism toward AGW among laypeople and policymakers".

- ^ Begley, 2007: "ICE and the Global Climate Coalition lobbied hard against a global treaty to curb greenhouse gases, and were joined by a central cog in the denial machine: the George C. Marshall Institute, a conservative think tank. ... the denial machine—think tanks linking up with like-minded, contrarian researchers"

- ^ Dunlap, 2013: "The campaign has been waged by a loose coalition of industrial (especially fossil fuels) interests and conservative foundations and think tanks ... These actors are greatly aided by conservative media and politicians, and more recently by a bevy of skeptical bloggers."

- ^ (EN) David Michaels, Doubt is Their Product: How Industry's Assault on Science Threatens Your Health., 2008.

- ^ (EN) James Hoggan e Richard Littlemore, Climate Cover-Up: The Crusade to Deny Global Warming, Vancouver, Greystone Books, 2009, pp. 31, 73, ISBN 978-1-55365-485-8. URL consultato il 19 marzo 2010. Si descrivono le strategie di sostegno fondate sull'industria nel contesto della negazione del cambiamento climatico e il coinvolgimento dei think tank liberisti nella negazione del riscaldamento globale.

- ^ (EN) Jordi Xifra, Climate Change Deniers and Advocacy: A Situational Theory of Publics Approach, in American Behavioral Scientist, vol. 60, n. 3, 2016, pp. 276–287, DOI:10.1177/0002764215613403.

- ^ Dunlap, 2013: "Even though climate science has now firmly established that global warming is occurring, that human activities contribute to this warming ... a significant portion of the American public remains ambivalent or unconcerned, and many policymakers (especially in the United States) deny the necessity of taking steps to reduce carbon emissions ... From the outset, there has been an organized 'disinformation' campaign ... to generate skepticism and denial concerning AGW."

- ^ Painter Ashe, 2012: "Despite a high degree of consensus amongst publishing climate researchers that global warming is occurring and that it is anthropogenic, this discourse, promoted largely by non-scientists, has had a significant impact on public perceptions of the issue, fostering the impression that elite opinion is divided as to the nature and extent of the threat."

- ^ (EN) ucsusa.org, The Disinformation Playbook – How Business Interests Deceive, Misinform, and Buy Influence at the Expense of Public Health and Safety.

- ^ (EN) Timothy Egan, Exxon Mobil and the G.O.P.: Fossil Fools, in The New York Times, 5 novembre 2015. URL consultato il 9 novembre 2015 (archiviato il 15 agosto 2021).

- ^ Suzanne Goldenberg, Exxon knew of climate change in 1981, email says – but it funded deniers for 27 more years, in The Guardian, 8 luglio 2015. URL consultato il 9 novembre 2015 (archiviato il 16 novembre 2015).

- ^ (EN) Damian Carrington, 'Shell knew': oil giant's 1991 film warned of climate change danger, in The Guardian, 2017 (archiviato dall'url originale il 24 aprile 2017).

- ^ Painter Ashe, 2012: "'Climate skepticism' and 'climate denial' are readily used concepts, referring to a discourse that has become important in public debate since climate change was first put firmly on the policy agenda in 1988. This discourse challenges the views of mainstream climate scientists and environmental policy advocates, contending that parts, or all, of the scientific treatment and political interpretation of climate change are unreliable."

- ^ a b National Center for Science Education, 2016: "There is debate ... about how to refer to the positions that reject, and to the people who doubt or deny, the scientific community's consensus on ... climate change. Many such people prefer to call themselves skeptics and describe their position as climate change skepticism. Their opponents, however, often prefer to call such people climate change deniers and to describe their position as climate change denial ... 'Denial' is the term preferred even by many deniers."

- ^ Nerlich, 2010, pp. 419, 437: "Climate scepticism in the sense of climate denialism or contrarianism is not a new phenomenon, but it has recently been very much in the media spotlight. ... Such disagreements are not new but the emails provided climate sceptics, in the sense of deniers or contrarians, with a golden opportunity to mount a sustained effort aimed at demonstrating the legitimacy of their views. This allowed them to question climate science and climate policies based on it and to promote political inaction and inertia. ... footnote 1. I shall use 'climate sceptics' here in the sense of 'climate deniers', although there are obvious differences between scepticism and denial (see Shermer, 2010; Kemp, et al., 2010). However, 'climate sceptic' and 'climate scepticism' were commonly used during the 'climategate' debate as meaning 'climate denier'."

- ^ Rennie, 2009: "Within the community of scientists and others concerned about anthropogenic climate change, those whom Inhofe calls skeptics are more commonly termed contrarians, naysayers and denialists."

- ^ Brown, 1996, pp. 9, 11 "Indeed, the 'skeptic' scientists14 were perceived to be all the more credible precisely because their views were contrary to the consensus of peer-reviewed science.

14. All scientists are skeptics because the scientific process demands continuing questioning. In this report, however, the scientists we refer to as 'skeptics' are those who have taken a highly visible public role in criticizing the scientific consensus on ozone depletion and climate change through publications and statements addressed more to the media and the public than to the scientific community." - ^ Gelbspan, 1998, pp. 69–70, 246 All'audizione del 16 novembre 1995 presso lo United States House Science Subcommittee on Energy, Pat Michaels testimoniò di "una piccola minoranza" contraria alla valutazione IPCC, e disse che "i cosiddetti scettici avevano ragione".

- ^ Antilla, 2005, nota a piè di pagina 5

- ^ Gelbspan, 1995

- ^ Painter Ashe, 2012: "The term 'climate scepticism' emerged in around 1995, the year journalist Ross Gelbspan authored perhaps the first book focusing directly on what would retrospectively be understood as climate scepticism."

- ^ Gelbspan, 1998 p. 3 "But some individuals do not want the public to know about the immediacy and extent of the climate threat. They have been waging a persistent campaign of denial and suppression that has been lamentably effective."

pp. 33–34 "The campaign to keep the climate change off the public agenda involves more than the undisclosed funding of these 'greenhouse skeptics.' In their efforts to challenge the consensus scientific view ".

p. 35 "If the climate skeptics have succeeded in confusing the general public, their influence on decision makers has been, if anything, even more effective"

p. 173 "pervasive denial of global warming" - ^ CBC News: the fifth estate , 2007: "The Denial Machine investigates the roots of the campaign to negate the science and the threat of global warming. It tracks the activities of a group of scientists, some of whom previously consulted for Big Tobacco, and who are now receiving donations from major coal and oil companies. ... The documentary shows how fossil fuel corporations have kept the global warming debate alive long after most scientists believed that global warming was real and had potentially catastrophic consequences. ... The Denial Machine also explores how the arguments supported by oil companies were adopted by policy makers in both Canada and the U.S. and helped form government policy."

- ^ a b Orlóci , 2008, pp. 86, 97: "The ideological justification for this came from the sceptics (e.g., Lomborg 2001a,b) and from the industrial 'denial machine'. ... CBC Television Fifth Estate, 15 November 2006, The Climate Denial Machine, Canada.

- ^ Begley, 2007: "If you think those who have long challenged the mainstream scientific findings about global warming recognize that the game is over, think again. ... outside Hollywood, Manhattan and other habitats of the chattering classes, the denial machine is running at full throttle—and continuing to shape both government policy and public opinion. Since the late 1980s, this well-coordinated, well-funded campaign by contrarian scientists, free-market think tanks and industry has created a paralyzing fog of doubt around climate change. Through advertisements, op-eds, lobbying and media attention, greenhouse doubters (they hate being called deniers) argued first that the world is not warming; measurements indicating otherwise are flawed, they said. Then they claimed that any warming is natural, not caused by human activities. Now they contend that the looming warming will be minuscule and harmless. 'They patterned what they did after the tobacco industry,' says former senator Tim Wirth"

- ^ Kari Norgaard, Living in Denial: Climate Change, Emotions, and Everyday Life, Cambridge, MA, MIT Press, 2011, pp. 1–4, ISBN 978-0-262-01544-8.

- ^ (EN) Michael E. Mann, The Hockey Stick and the Climate Wars: Dispatches from the Front Lines, Columbia University Press, 2013, ISBN 978-0-231-52638-8.«Skepticism plays an essential role in the progress of science ... Yet ... in the context of the climate change denial movement ... the term skeptic has often been co-opted to describe those who simply deny, rather than appraise critically.»

- ^ Jenkins, 2015, p. 229: "many who deny the consensus on climate change are not really skeptics but rather contrarians who practice "a kind of one-sided skepticism that entails simply rejecting evidence that challenges one's preconceptions" (Mann 2012:26)"

- ^ a b National Center for Science Education, 2016: "Recognizing that no terminological choice is entirely unproblematic, NCSE—in common with a number of scholarly and journalistic observers of the social controversies surrounding climate change—opts to use the terms "climate change deniers" and "climate change denial. The terms are intended descriptively, not in any pejorative sense, and are used for the sake of brevity and consistency with a well-established usage in the scholarly and journalistic literature."

- ^ Weart, 2015, The Public and Climate, cont. footnote 136a, su aip.org, 10 febbraio 2015. URL consultato il 18 giugno 2022 (archiviato dall'url originale il 10 febbraio 2015).«I do not mean to use the term 'denier' pejoratively—it has been accepted by some of the group as a self-description—but simply to designate those who deny any likelihood of future danger from anthropogenic global warming.»

- ^ (EN) William R. L. Anderegg, James W. Prall e Jacob Harold, Reply to O'Neill and Boykoff: Objective classification of climate experts, in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 107, n. 39, 19 luglio 2010, pp. E152, Bibcode:2010PNAS..107E.152A, DOI:10.1073/pnas.1010824107, ISSN 0027-8424, PMC 2947900.

- ^ a b (EN) Justin Gillis, Verbal Warming: Labels in the Climate Debate, in The New York Times, 12 febbraio 2015. URL consultato il 30 giugno 2015 (archiviato il 30 ottobre 2021).

- ^ Timmer, 2014: "some of the people who deserve that label are offended by it, thinking it somehow lumps them in with Holocaust deniers. But that in its own way is a form of denial; the word came into use before the Holocaust, and ... denialism has been used as a label for people who refuse to accept the evidence for all sorts of things: HIV causing AIDS, vaccines being safe, etc."

- ^ Boslough , 2014

- ^ Il public editor è una posizione esistente in alcune testate giornalistiche; la persona che ricopre questa posizione è responsabile della supervisione dell'attuazione di una corretta etica giornalistica in quella pubblicazione. Queste responsabilità includono l'identificazione e l'esame di errori o omissioni critiche e la funzione di collegamento con il pubblico. Nella maggior parte dei casi, i public editor svolgono questo lavoro attraverso una rubrica regolare nella pagina editoriale di un giornale. Poiché i public editor sono generalmente dipendenti dello stesso giornale che criticano, può sembrare che ci sia un conflitto di interessi. Tuttavia, un giornale con un elevato standard etico non licenzierebbe un public editor per una critica al giornale; l'atto sarebbe in contraddizione con lo scopo della posizione e sarebbe di per sé una probabile causa di preoccupazione per l'opinione pubblica.

- ^ Andrew Seifter e Joe Strupp, NY Times Public Editor: We're 'Moving In A Good Direction' On Properly Describing Climate Deniers, su Media Matters for America, 22 giugno 2015. URL consultato il 2 luglio 2015 (archiviato il 23 aprile 2019).

- ^ AP: Deniers Are Not Skeptics!, su Oil Change U.S.. URL consultato il 22 maggio 2019 (archiviato il 5 maggio 2021).

- ^ (EN) Paul Colford, An addition to AP Stylebook entry on global warming, su Associated Press, 22 settembre 2015. URL consultato il 7 ottobre 2019.

- ^ Zoë Schlanger, The real skeptics behind the AP decision to put an end to the term 'climate skeptics', in Newsweek, 24 settembre 2015. URL consultato il 22 maggio 2019 (archiviato il 1º giugno 2021).

- ^ (EN) Damian Carrington, Why The Guardian is changing the language it uses about the environment, in The Guardian, 17 maggio 2019. URL consultato il 22 maggio 2019 (archiviato il 6 ottobre 2019).

- ^ Conway Oreskes, 2010, p. 170: "The doubts and confusion of the American people are particularly peculiar when put into historical perspective"

- ^ Powell, 2012, pp. 36–39

- ^ Weart, 2015a: "From the late 1940s into the 1960s, many of the papers cited in these essays carried a thought-provoking footnote: "This work was supported by the 'Office of Naval Research.' "

- ^ Weart, 2007

- ^ Weart, 2015a: quote p. viii in the Foreword by Climate Research Board chair Verner E. Suomi

- ^ Jule Gregory Charney, Carbon Dioxide and Climate: A Scientific Assessment, Report of an Ad Hoc Study Group on Carbon Dioxide and Climate, Woods Hole, MA, National Research Council, 23 luglio 1979, DOI:10.17226/12181, ISBN 978-0-309-11910-8. URL consultato il 22 settembre 2017.

- ^ (EN) March Hudson, US firms knew about global warming in 1968 – what about Australia?, su The Conversation, 2016. URL consultato il 19 agosto 2018 (archiviato il 10 novembre 2021).

- ^ a b (EN) Élan Young, Coal Knew, Too, A Newly Unearthed Journal from 1966 Shows the Coal Industry, Like the Oil Industry, Was Long Aware of the Threat of Climate Change, in Huffington Post, 22 novembre 2019. URL consultato il 24 novembre 2019 (archiviato il 22 febbraio 2020).

- ^ I presidenti degli Stati Uniti sono soliti completare i loro gabinetti e altre posizioni di nomina con persone del loro stesso partito politico. Il primo Gabinetto formato dal primo presidente, George Washington, comprendeva alcuni degli avversari politici di Washington, ma i presidenti successivi hanno adottato la pratica di completare i loro gabinetti con membri del proprio partito. Le nomine trasversali ai partiti non sono frequenti. I presidenti possono nominare membri di un altro partito a posizioni di alto livello per ridurre la partigianeria o migliorare la cooperazione tra i partiti politici. Inoltre, i presidenti spesso nominano membri di un altro partito perché per molte di queste posizioni è necessaria la conferma del Senato, e al momento della nomina il Senato era controllato dal partito di opposizione del presidente. Molti dei nominati trasversali sono spesso moderati all'interno del loro stesso partito. Non è mai stato nominato un membro di un terzo partito (diverso, cioè, dal Partito Democratico e dal Repubblicano).

- ^ Emma Pattee, The 1977 White House climate memo that should have changed the world, in The Guardian, 14 giugno 2022. URL consultato il 14 giugno 2022.

- ^ Weart, 2015a: Global Warming Becomes a Political Issue (1980–1983) (archiviato dall'url originale il 29 giugno 2016).; "In 1981, Ronald Reagan took the presidency with an administration that openly scorned their concerns. He brought with him a backlash that had been building against the environmental movement. Many conservatives denied nearly every environmental worry, global warming included. They lumped all such concerns together as the rants of business-hating liberals, a Trojan Horse for government regulation." For details, see Money for Keeling: Monitoring CO2 (archiviato dall'url originale il 29 giugno 2016).

- ^ Spencer R. Weart, The Discovery of Global Warming, Harvard University Press, 2009, ISBN 978-0-674-04497-5. URL consultato il 16 marzo 2016 (archiviato il 1º giugno 2021).

- ^ Weart, 2015: Breaking into Politics (1980–1988) (archiviato dall'url originale il 29 giugno 2016)., "Sherwood Idso, who published arguments that greenhouse gas emissions would not warm the Earth or bring any other harm to the climate. Better still, by fertilizing crops, the increase of CO2 would bring tremendous benefits."

- ^ James Hansen, Statement of Dr. James Hansen, director, NASA Goddard Institute for space studies (PDF), su Climate Change ProCon.org, 1988. URL consultato il 30 novembre 2015 (archiviato dall'url originale il 22 agosto 2011).

- ^ Philip Shabecoff, Global Warming Has Begun, Expert Tells Senate, in The New York Times, 24 giugno 1988.

- ^ Weart, 2015 The Summer of 1988 (archiviato dall'url originale il 29 giugno 2016).: "A new breed of interdisciplinary studies was showing that even a few degrees of warming might have harsh consequences, both for fragile natural ecosystems and for certain agricultural systems and other human endeavours ... The timing was right, and the media leaped on the story. Hansen's statements, especially that severe warming was likely within the next 50 years, got on the front pages of newspapers and were featured in television news and radio talk shows ... The story grew as the summer of 1988 wore on. Reporters descended unexpectedly upon an international conference of scientists held in Toronto at the end of June. Their stories prominently reported how the world's leading climate scientists declared that atmospheric changes were already causing harm, and might cause much more; the scientists called for vigorous government action to restrict greenhouse gases."

- ^ Weart, 2015: "Environmentalist organizations continued ... lobbying and advertising efforts to argue for restrictions on emissions. The environmentalists were opposed and greatly outspent, by industries that produced or relied on fossil fuels. Industry groups not only mounted a sustained and professional public relations effort but also channeled considerable sums of money to individual scientists and small conservative organizations and publications that denied any need to act against global warming."

- ^ a b Begley, 2007: "Through advertisements, op-eds, lobbying and media attention, greenhouse doubters (they hate being called deniers) argued first that the world is not warming ... Then they claimed that any warming is natural ... Now they contend that the looming warming will be minuscule and harmless. 'They patterned what they did after the tobacco industry,' says former senator Tim Wirth ... 'Both figured, sow enough doubt, call the science uncertain and in dispute. That's had a huge impact on both the public and Congress.'"

- ^ a b Weart, 2015: "The technical criticism most widely noted in the press came in several brief 'reports'—not scientific papers in the usual sense—published between 1989 and 1992 by the conservative George C. Marshall Institute. The anonymously authored pamphlets ... [claimed] that proposed government regulation would be 'extraordinarily costly to the U.S. economy,' they insisted it would be unwise to act on the basis of the existing global warming theories ... In 1989 some of the biggest corporations in the petroleum, automotive, and other industries created a Global Climate Coalition, whose mission was to disparage every call for action against global warming."

- ^ a b Conway Oreskes, 2010: "Millions of pages of documents released during tobacco litigation ... show the crucial role that scientists played in sowing doubt about the links between smoking and health risks. These documents ... also show that the same strategy was applied not only to global warming, but to a laundry list of environmental and health concerns, including asbestos, secondhand smoke, acid rain, and the ozone hole."

- ^ Weart, 2015: "Scientists noticed something that the public largely overlooked: the most outspoken scientific critiques of global warming predictions did not appear in the standard peer-reviewed scientific publications. The critiques tended to appear in venues funded by industrial groups, or in conservative media like the Wall Street Journal."

- ^ a b Conway Oreskes, 2010

- ^ Weart, 2011, p. 46: "Scientists continually test their beliefs, seeking out all possible contrary arguments and evidence, and finally publish their findings in peer-reviewed journals, where further attempts at refutation are encouraged. But the small group of scientists who opposed the consensus on warming proceeded in the manner of lawyers, considering nothing that would not bolster their case, and publishing mostly in pamphlets, books, and newspapers supported by conservative interests. At some point they were no longer skeptics—people who would try to see every side of a case—but deniers, that is, people whose only interest was in casting doubt upon what other scientists agreed was true."

- ^ Weart, 2011, p. 47: "As the deniers found ever less scientific ground to stand on, they turned to political arguments. Some of these policy arguments were straightforward, raising serious questions about the efficacy and expense of proposed carbon taxes and emission-regulation schemes. But leading deniers also resorted to ad hominem tactics ... On each side, some people were coming to believe that they faced a dishonest conspiracy, driven by ideological bias and naked self-interest".

- ^ Jacques Dunlap Freeman, 2008, pp. 349–385: "Environmental skepticism encompasses several themes, but denial of the authenticity of environmental problems, particularly problems such as biodiversity loss or climate change that threaten ecological sustainability, is its defining feature"

- ^ a b Hamilton 2011, pp. 104–106: "the tactics, personnel, and organisations mobilised to serve the interests of the tobacco lobby in the 1980s were seamlessly transferred to serve the interests of the fossil-fuel lobby in the 1990s. Frederick Seitz ... the task of the climate sceptics in the think tanks and PR companies hired by fossil fuel companies was to engage in 'consciousness lowering activities', to 'de-problematise' global warming by describing it as a form of politically driven panicmongering." Per la nota dell'impresa del tabacco, vedi Original "Doubt is our product ..." memo, su legacy.library.ucsf.edu, University of California, San Francisco, 21 agosto 1969. URL consultato il 19 marzo 2010 (archiviato il 2 aprile 2015).

- ^ Conway, Oreskes, 2010. p. 105: "As recently as 2007, the George Marshall Institute continued to insist that the damages associated with acid rain were always 'largely hypothetical,' and that 'further scientific investigation revealed that most of them were not in fact occurring.' The Institute cited no studies to support this extraordinary claim."

- ^ Weart, 2015: "Public support for environmental concerns, in general, seems to have waned after 1988."

- ^ Weart, 2015: "A study of American media found that in 1987 most items that mentioned the greenhouse effect had been feature stories about the science, whereas in 1988 the majority of the stories addressed the politics of the controversy. It was not that the number of science stories declined, but rather that as media coverage doubled and redoubled, the additional stories moved into social and political areas ... Before 1988, the journalists had drawn chiefly on scientists for their information, but afterward, they relied chiefly on sources who were identified with political positions or special interest groups."

- ^ Matthew L. Wald, Pro-Coal Ad Campaign Disputes Warming Idea, in The New York Times, 8 luglio 1991. URL consultato il 1º marzo 2013 (archiviato il 14 agosto 2021).

- ^ Begley, 2007: "Individual companies and industry associations—representing petroleum, steel, autos, and utilities, for instance—formed lobbying groups ... [the Information Council on the Environment's] game plan called for enlisting greenhouse doubters to 'reposition global warming as theory rather than fact,' and to sow doubt about climate research just as cigarette makers had about smoking research ... The coal industry's Western Fuels Association paid Michaels to produce a newsletter called World Climate Report, which has regularly trashed mainstream climate science."

- ^ Robert Cox, Environmental Communication and the Public Sphere, Sage, 2009, pp. 311–312.«to recruit a cadre of scientists who share the industry's views of climate science and to train them in public relations so they can help convince journalists, politicians and the public that the risk of global warming is too uncertain to justify controls on greenhouse gases»

- ^ Cushman, John, "Industrial Group Plans to Battle Climate Treaty" Archiviato il 3 luglio 2021 in Internet Archive., The New York Times, 25 April 1998. consultato il 10 marzo 2010.

- ^ Gelbspan, 1998

- ^ Michael A. Milburn e Sheree D. Conrad, The Politics of Denial, MIT Press, 1998, pp. 216–, ISBN 978-0-262-63184-6. URL consultato il 12 luglio 2015 (archiviato il 22 marzo 2021).«Here again, as in the case of ozone depletion, economic and psychological forces are operating to produce a level of denial that threatens future generations.»

- ^ Painter, Ashe, 2012: "Academics took note of the discourse when they began to analyse media representations of climate change knowledge and its effect on public perceptions and policy-making, but in the 1990s, they did not yet focus on it as a coherent and defined phenomenon. This changed in the 2000s when McCright and Dunlap played an important role in deepening the concept of climate skepticism."

- ^ Painter, Ashe, 2012:"McCright and Dunlap played an important role in deepening the concept of climate skepticism. Examining what they termed a 'conservative countermovement' to undermine climate change policy ... McCright and Dunlap went beyond the study of media representations of climate change knowledge to give a coherent picture of the movement behind climate skepticism in the US."

- ^ Jacques, Dunlap, Freeman, 2008 pp. 349–385

- ^ Eric Roston, Unearthing America's Deep Network of Climate Change Deniers, su Bloomberg News, 30 novembre 2015. URL consultato il 6 marzo 2017 (archiviato il 10 novembre 2021).

- ^ Justin Farrell, Network structure and influence of the climate change counter-movement, in Nature Climate Change, vol. 6, n. 4, 2015, pp. 370–374, Bibcode:2016NatCC...6..370F, DOI:10.1038/nclimate2875.

Bibliografia

- Liisa Antilla, Climate of scepticism: US newspaper coverage of the science of climate change, in Global Environmental Change, vol. 15, n. 4, 2005, pp. 338–352, DOI:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2005.08.003.

- Sharon Begley, The Truth About Denial, in Newsweek, 13 agosto 2007 (archiviato dall'url originale il 21 ottobre 2007). ( MSNBC single p version, archived 20 August 2007 (archiviato dall'url originale il 20 agosto 2007).)

- Karin Edvardsson Björnberg, Climate and environmental science denial: A review of the scientific literature published in 1990–2015, in Journal of Cleaner Production, vol. 167, 2017, pp. 229–241, DOI:10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.08.066.

- Mark Boslough, Deniers are not Skeptics, su Committee for Skeptical Inquiry, 5 dicembre 2014. URL consultato il 7 luglio 2015 (archiviato dall'url originale il 16 marzo 2019).

- R. G. E. Jr. Brown, Environmental science under siege: Fringe science and the 104th Congress, U. S. House of Representatives. (PDF), in Report, Democratic Caucus of the Committee on Science, Washington, D.C., U. S. House of Representatives, 23 ottobre 1996 (archiviato dall'url originale il 26 settembre 2007).

- CBC News: the fifth estate, The Denial Machine, su cbc.ca, 2007. URL consultato il 29 luglio 2015 (archiviato dall'url originale il 12 marzo 2007).

- Erik Conway e Naomi Oreskes, Merchants of Doubt: How a Handful of Scientists Obscured the Truth on numeros from Tobacco Smoke to Global Warming, US, Bloomsbury, 2010, p. 170., ISBN 978-1-59691-610-4.

- Pascal Diethelm e Martin McKee, Denialism: what is it and how should scientists respond?, in European Journal of Public Health, vol. 19, n. 1, gennaio 2009, pp. 2–4, DOI:10.1093/eurpub/ckn139, PMID 19158101.

- Riley E Dunlap e Aaron M. McCright, Climate Change Denial: Sources, actors, and strategies, Taylor & Francis, 2011, ISBN 978-0-415-54478-8.

- Riley E. Dunlap, Climate Change Skepticism and Denial: An Introduction, in American Behavioral Scientist, vol. 57, n. 6, 2013, pp. 691–698, DOI:10.1177/0002764213477097. URL consultato il 27 maggio 2015 (archiviato dall'url originale il 10 novembre 2021).

- Riley E. Dunlap e Aaron M. McCright, Organised Climate Change Denial, in John S. Dryzek, Richard B. Norgaard e David Schlosberg (a cura di), The Oxford Handbook of Climate Change and Society, Oxford University Press, 2011, p. 153, ISBN 978-0-19-956660-0. URL consultato il 6 settembre 2015 (archiviato dall'url originale il 1º giugno 2021).

- R. E. Dunlap e P. J. Jacques, Climate Change Denial Books and Conservative Think Tanks: Exploring the Connection, in American Behavioral Scientist, vol. 57, n. 6, 2013, pp. 699–731, DOI:10.1177/0002764213477096, PMC 3787818, PMID 24098056.

- Ross Gelbspan, The heat is on: The warming of the world's climate sparks a blaze of denial, in Harper's Magazine, dicembre 1995. URL consultato il 2 giugno 2015 (archiviato dall'url originale il 7 marzo 2016).

- Ross Gelbspan, The Heat is on: The High Stakes Battle Over Earth's Threatened Climate, Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, 1997, ISBN 978-0-201-13295-3.

- Ross Gelbspan, The heat is on : the climate crisis, the cover-up, the prescription, Reading, MA, Perseus Books, 1998, ISBN 978-0-7382-0025-5.

- Clive Hamilton, Requiem for a Species: Why We Resist the Truth about Climate Change, Routledge, 2011, ISBN 978-1-84977-498-7. URL consultato il 16 marzo 2016 (archiviato dall'url originale il 23 marzo 2021).

- P.J. Jacques, Riley E. Dunlap e M. Freeman, The organisation of denial: Conservative think tanks and environmental scepticism, in Environmental Politics, vol. 17, n. 3, 2008, pp. 349–385, DOI:10.1080/09644010802055576.

- Stephen H. Jenkins, Tools for Critical Thinking in Biology, Oxford University Press, 2015, pp. 229, 243, ISBN 978-0-19-998104-5. URL consultato il 16 marzo 2016 (archiviato dall'url originale il 22 marzo 2021).

- Jeremy Kemp, Richard Milne e Dave S. Reay, Sceptics and deniers of climate change not to be confused, in Nature, vol. 464, n. 7289, 2010, pp. 673, Bibcode:2010Natur.464..673K, DOI:10.1038/464673a, PMID 20360714. URL consultato il 7 settembre 2015 (archiviato dall'url originale il 10 novembre 2021).

- Constance Lever-Tracy, Routledge Handbook of Climate Change and Society, Taylor & Francis, 2010, ISBN 978-0-203-87621-3. URL consultato il 12 luglio 2015 (archiviato dall'url originale il 6 maggio 2016).

- Chris Mooney, The Republican war on science, New York, Basic Books, 2005, ISBN 978-0-465-04675-1. URL consultato il 4 luglio 2015 (archiviato dall'url originale il 3 novembre 2021).

- National Center for Science Education, Why Is It Called Denial?, su ncse.ngo, National Center for Science Education, 15 gennaio 2016. URL consultato il 17 febbraio 2023 (archiviato dall'url originale il 7 dicembre 2022).

- Brigitte Nerlich, 'Climategate': Paradoxical Metaphors and Political Paralysis, in Environmental Values, vol. 19, n. 4, 2010, pp. 419–442, DOI:10.3197/096327110x531543. URL consultato il 4 luglio 2015 (archiviato dall'url originale il 10 novembre 2021).

- L. Orlóci, Vegetation displacement numeros and transition statistics in climate warming cycle, in Community Ecology, vol. 9, n. 1, 2008, pp. 83–98, DOI:10.1556/comec.9.2008.1.10. URL consultato il 29 luglio 2015 (archiviato dall'url originale il 10 novembre 2021).

- James Painter e Teresa Ashe, Cross-national comparison of the presence of climate scepticism in the print media in six countries, 2007, in Environ. Res. Lett., vol. 7, n. 4, 2012, p. 044005, Bibcode:2012ERL.....7d4005P, DOI:10.1088/1748-9326/7/4/044005.

- James Lawrence Powell, The Inquisition of Climate Science, Columbia University Press, 2012, ISBN 978-0-231-15719-3. URL consultato il 12 luglio 2015 (archiviato dall'url originale il 1º giugno 2021).

- John Rennie, Seven Answers to Climate Contrarian Nonsense, in Scientific American, 30 novembre 2009. URL consultato il 7 luglio 2015 (archiviato dall'url originale il 19 ottobre 2017).

- John Timmer, Skeptics, deniers, and contrarians: The climate science label game, in Ars Technica, 16 dicembre 2014. URL consultato il 14 giugno 2017 (archiviato dall'url originale il 2 ottobre 2017).

- Gayathri Vaidyanathan, What Have Climate Scientists Learned from 20-anno Fight with Deniers?, in Scientific American, 2014. URL consultato il 23 gennaio 2016 (archiviato dall'url originale il 20 agosto 2021).

- Haydn Washington, Climate Change Denial: Heads in the Sand, Routledge, 2013, ISBN 978-1-136-53004-3.

- Spencer R. Weart, Roger Revelle's Discovery, in The Discovery of Global Warming, American Institute of Physics, luglio 2007. URL consultato il 18 luglio 2015 (archiviato dall'url originale il 29 giugno 2016).

- Spencer R. Weart, The Public and Climate, cont., in The Discovery of Global Warming, American Institute of Physics, febbraio 2015. URL consultato il 18 giugno 2022 (archiviato dall'url originale il 10 febbraio 2015).

- Spencer R. Weart, Government: The View from Washington, DC, in The Discovery of Global Warming, American Institute of Physics, giugno 2015. URL consultato il 18 luglio 2015 (archiviato dall'url originale il 29 giugno 2016).

- Spencer Weart, Global warming: How skepticism became denial (PDF), in Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, vol. 67, n. 1, 2011, pp. 41–50, Bibcode:2011BuAtS..67a..41W, DOI:10.1177/0096340210392966 (archiviato dall'url originale il 10 giugno 2015).