Utente:Parsec09/Freedoms of the air (1)

Le "freedoms of the air" ("Libertà dell'aria") sono una serie di diritti di aviazione commerciale che concedono alle compagnie aeree di un paese il privilegio di entrare e atterrare nello spazio aereo di un altro paese. Sono state formulate a seguito di disaccordi sull'estensione della liberalizzazione dell'aviazione nella Convenzione sull'aviazione civile internazionale del 1944, nota come la Convenzione di Chicago. Gli Stati Uniti avevano richiesto una serie standardizzata di diritti aerei separati da negoziare tra gli stati, ma la maggior parte degli altri paesi era preoccupata che le dimensioni delle compagnie aeree statunitensi avrebbero dominato il trasporto aereo se non ci fossero state regole rigide. Le libertà dell'aria sono gli elementi costitutivi fondamentali della rete internazionale di rotte aeree. L'uso dei termini "libertà" e "diritto" conferisce il diritto di operare servizi aerei internazionali solo nell'ambito dei trattati multilaterali e bilaterali (accordi sui servizi aerei) che li consentono.

Le prime due libertà riguardano il transito di aerei commerciali attraverso lo spazio aereo e gli aeroporti stranieri, le altre libertà riguardano il trasporto di persone, posta e merci a livello internazionale. Le libertà dal primo al quinto livello sono enumerate ufficialmente dai trattati internazionali, in particolare dalla Convenzione di Chicago. Sono state aggiunte molte altre libertà e, benché la maggior parte non sia ufficialmente riconosciuta in base a trattati internazionali ampiamente applicabili, sono di fatto in vigore tra alcuni paesi. Le libertà di indice inferiore sono relativamente universali, mentre le maggiori sono più rare e controverse. Gli accordi liberali per i cieli aperti rappresentano spesso la forma meno restrittiva degli accordi sui servizi aerei e possono includere molte (se non tutte) le libertà. Sono relativamente rari, ma esistono ad esempio i recenti mercati dell'aviazione unica stabiliti nell'Unione europea e tra l'Australia e la Nuova Zelanda.

Overview

[modifica | modifica wikitesto]Le libertà dell'aria si applicano all'aviazione commerciale.[1]145–146 I termini "libertà" e "diritto" sono un modo sintetico di riferirsi al tipo di servizi internazionali concordati tra due o più paesi145–146. Anche quando tali servizi sono consentiti dai paesi, le compagnie aeree possono comunque incontrare restrizioni per usufruirne, in base ai termini dei trattati o per altri motivi.145–14619

| Libertà | Descrizione | Esempio | Esempio di volo |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1° | Il diritto di sorvolare un paese straniero senza atterrare[2]. | Un volo dal Canada al Messico, operato da una compagnia messicana, sorvolando gli Stati Uniti. | Aeromexico, una compagnia messicana, opera il volo AM 613 da Calgary a Città del Messico. |

| 2° | Il diritto al rifornimento o alla manutenzione in un paese straniero senza imbarco o sbarco di passeggeri o merci. | Un volo dal Regno Unito verso gli Stati Uniti, operato da una compagnia britannica, con rifornimento di carburante in un aeroporto irlandese. | British Airways opera il volo BA 1 dall'aeroporto di London City all'aeroporto John F. Kennedy di New York, con scalo all'aeroporto di Shannon in Irlanda per il rifornimento, durante il quale i passeggeri completano le formalità per l'immigrazione negli Stati Uniti. Il volo inverso non ha una fermata intermedia. |

| 3° | Il diritto di volare dal proprio paese ad un altro paese. | Un volo dalla Nuova Zelanda al Giappone, operato da una compagnia neozelandese. | Volo NZ 99 da Auckland a Tokyo-Narita dalla neozelandese Air New Zealand. |

| 4° | Il diritto di volare da un altro paese al proprio. | Un volo dal Cile al Brasile, operato da una compagnia brasiliana. | Gol, una compagnia aerea brasiliana, opera il volo G3 9246 da Santiago a Rio de Janeiro. |

| 5° | Il diritto di volare tra due paesi stranieri su un volo che ha origine o termina nel proprio paese. | Un volo da Dubai, negli Emirati Arabi Uniti a Christchurch, in Nuova Zelanda, effettuato da Emirates con scalo a Sydney, in Australia. Passeggeri e merci possono viaggiare tra Christchurch e Sydney, senza intenzione di continuare a Dubai. | Emirates opera il volo EK 412 dall'Aeroporto Internazionale di Dubai a quello di Christchurch con scalo all'Aeroporto Internazionale di Sydney. I passeggeri possono imbarcarsi e sbarcare anche a Sydney. |

| 6° | Il diritto di volare da un paese straniero a un altro fermandosi nel proprio per motivi non tecnici. | Un volo dalla Nuova Zelanda agli Stati Uniti con scalo a Tahiti, operato da una compagnia tahitiana. | Air Tahiti, una compagnia tahitiana, opera il volo TN 102 from Auckland to Los Angeles through Papeete, Tahiti. |

| 6° (modificato) |

The right to fly between two places in a foreign country while stopping in one's own country for non-technical reasons. | A flight flown from the United States to another airport also in the United States, flown by an airline based in Canada, with a full stop in Canada. | Air Canada Express, a Canadian airline, operates flight AC 1100 from New York City-JFK Airport to Anchorage through Calgary. |

| 7° | The right to fly between two foreign countries while not offering flights to one's own country. | A flight between Portugal and Germany, flown by an Irish airline. | Ryanair, an Irish airline, flies FR 1143 from Lisbon (LIS) to Berlin Schönefeld (SXF). |

| 8° | The right to fly inside a foreign country, continuing to one's own country. | A flight operated by a French airline between San Francisco and Paris, with a full stop in Newark. Passengers and cargo may board or disembark the flight in Newark, with no intention to continue the flight to Paris. | Air France, a French airline, flies AF 154, from San Francisco (SFO) to Paris (CDG) through Newark (EWR). |

| 9° | The right to fly within a foreign country without continuing to one's own country. | A flight flown between Auckland and Christchurch by an Australian airline. | Jetstar's New Zealand domestic network. Those flights are operated by Australian-registered company using Airbus A320 and Bombardier Dash 8 fleets registered in Australia. |

Transit rights

[modifica | modifica wikitesto]The first and second freedoms grant rights to pass through a country without carrying traffic that originates or terminates there and are known as 'transit rights'.[3]146 The Chicago Convention drew up a multilateral agreement in which the first two freedoms, known as the International Air Services Transit Agreement (IASTA) or "Two Freedoms Agreement", were open to all signatories. As of mid-2007, the treaty was accepted by 129 countries.[4]

First freedom

[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

The first freedom is the right to fly over a foreign country without landing.[5]31 It grants the privilege to fly over the territory of a treaty country without landing. Member states of the International Air Services Transit Agreement grant this freedom (as well as the second freedom) to other member states,[6] subject to the transiting aircraft using designated air routes. As of the summer of 2007, 129 countries were parties to this treaty, including such large ones as the United States of America, India, and Australia. However, Brazil, Russia, Indonesia, and China never joined, and Canada left the treaty in 1988.[7] These large and strategically located non-IASTA-member states prefer to maintain tighter control over foreign airlines' overflight of their airspace, and negotiate transit agreements with other countries on a case-by-case basis.[8]23 Since the end of the Cold War, first freedom rights are almost completely universal.151 Most countries require prior notification before an overflight, and may charge substantial fees for the privilege.[9]

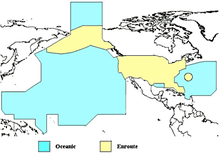

IASTA allows each member country to charge foreign airlines "reasonable" fees for using its airports (which is applicable, presumably, only to the second freedom) and "facilities";[10] according to IATA, such fees should not be higher than those charged to domestic airlines engaged in similar international services. Such fees indeed are commonly charged merely for the privilege of the overflight of a country's national territory, when no airport usage is involved.[11] (Although it should be noted that overflights might still be using services of a country's Air Traffic Control Centers). For example, the Federal Aviation Administration of the U.S., an IASTA signatory, charges the so-called en route fees, of $58.45 (US$60.08 beginning 1 January 2018) per 100 miglia nautiche (190 km), of great circle distance from point of entry of an aircraft into the U.S.-controlled airspace to the point of its exit from this airspace.[12] In addition, a lower fee—the oceanic fee—is charged ($23.15 per 100 miglia nautiche (190 km); $24.77 beginning 1 January 2018) for flying over the international waters where air traffic is controlled by the U.S., which includes sections of Atlantic & Arctic Oceans and much of the northern Pacific Ocean. Countries that are not signatories of the IASTA charge overflight fees as well; among them, Russia, is known for charging high fees, especially on the transarctic routes between North America and Asia, which cross Siberia. In 2008, Russia temporarily denied Lufthansa Cargo permission to overfly its airspace with cargo ostensibly due to "delayed payments for its flyover rights".[13] European airlines pay Russia €300 million a year for flyover permissions.

Second freedom

[modifica | modifica wikitesto]The second freedom allows technical stops without the embarking or disembarking of passengers or cargo.31 It is the right to stop in one country solely for refueling or other maintenance on the way to another country.146 Because of longer range of modern airliners, second freedom rights are comparatively rarely exercised by passenger carriers today, but they are widely used by air cargo carriers, and are more or less universal between countries.

The most famous example of the second freedom is Shannon Airport (Ireland), which was used as a stopping point for most transatlantic flights until the 1960s, since Shannon Airport was considered the closest European airport to the United States. Anchorage was similarly used for flights between Western Europe and East Asia, bypassing the prohibited Soviet airspace, until the end of the Cold War. Anchorage was still used by some Chinese and Taiwanese airlines for flights to the U.S. and Toronto until the 2000s. Flights between Europe and South Africa often stopped at Ilha do Sal (Sal Island) in Cabo Verde, off the coast of Senegal, due to many African nations refusing to allow South African flights to overfly their territory during the Apartheid regime. Gander, Newfoundland was also a frequent stopping point for airlines from the USSR and East Germany on the way to the Caribbean, Central America, Mexico and South America.

Traffic rights

[modifica | modifica wikitesto]In contrast to transit rights, 'traffic rights' allow commercial international services between, through and in some cases within the countries that are parties to air services agreements or other treaties.146 While it was agreed that the third to fifth freedoms would be negotiated between states, the International Air Transport Agreement (or "Five Freedoms Agreement") was also opened for signatures, encompassing the first five freedoms.108 The remaining four freedoms are made possible by some air services agreements but are not 'officially' recognized because they are not mentioned by the Chicago Convention.108

Third and fourth freedom

[modifica | modifica wikitesto]The third and fourth freedoms allow basic international service between two countries.146 Even when reciprocal third and fourth freedom rights are granted, air services agreements (e.g. the Bermuda Agreements) may still restrict many aspects of the traffic, such as the capacity of aircraft, the frequency of flights, the airlines permitted to fly and the airports permitted to be served.146–147 The third freedom is the right to carry passengers or cargo from one's own country to another.31 The right to carry passengers or cargo from another country to one's own is the fourth freedom.31 Third and fourth freedom rights are almost always granted simultaneously in bilateral agreements between countries.

Beyond rights

[modifica | modifica wikitesto]Beyond rights allow the carriage of traffic between (and sometimes within) countries that are foreign to the airlines that operate them.146 Today, the most controversial of these are fifth freedom rights.146[14]108–109112 Less controversial but still restricted at times, though relatively more common are sixth freedom rights.146[15]94–95

Beyond rights also encompass international flights with a foreign intermediate stop where passengers may only embark and disembark at the intermediate point on the leg of the flight that serves the origin of an airline operating it.146 It also includes 'stopover' traffic where passengers may embark or disembark at an intermediate stop as part of an itinerary between the endpoints of a multi-leg flight or connecting flights.[16]146 Some international flights stop at multiple points in a foreign country and passengers may sometimes make stopovers in a similar manner, but because the traffic being carried does not originate in the country where the flight takes place it is not cabotage but another form of beyond rights.[17]110

Fifth freedom

[modifica | modifica wikitesto]The fifth freedom allows an airline to carry revenue traffic between foreign countries as a part of services connecting the airline's own country.[18] It is the right to carry passengers from one's own country to a second country, and from that country to a third country (and so on). An example of a fifth freedom traffic right is an Emirates flight in 2004 from Dubai to Brisbane, Australia and onward to Auckland, New Zealand, where tickets can be sold on any sector.34 Fifth freedom traffic rights are intended to enhance the economic viability of an airline's long haul routes, but tend to be viewed by local airlines and governments as potentially unfair competition.33–34 The negotiations for fifth freedom traffic rights can be lengthy, because in practice the approval of at least three different nations is required.[16]131Fifth freedom traffic rights were instrumental to the economic viability of long-haul flight until the early 1980s, when advances in technology and increased passenger volume enabled the operation of more non-stop flights.31–32 The excess capacity on multi-sector routes could be filled by picking up and dropping off passengers along the way.33 It was not uncommon for carriers to schedule stops in one or more foreign countries on the way to a flight's final destination. Fifth freedom flights were common between Europe and Africa, South America and the Far East.31–32 An example of a multi-sector flight in the mid-1980s was an Alitalia service from Rome to Tokyo via Athens, Delhi, Bangkok and Hong Kong.31–32 Such routings in Asia approximated the Silk Road.31–32 Fifth freedom flights are still highly common in East Asia, particularly on routes serving Tokyo, Hong Kong and Bangkok. Between the latter two destinations, in 2004, service was provided by at least four airlines whose home base was not in either Hong Kong or Bangkok.32 The Singapore-Bangkok route has also constituted an important fifth freedom market. In the late 1990s, half of the seats available between the two cities were offered by airlines holding fifth freedom traffic rights.112 Other major markets served by fifth freedom flights can be found in Europe, South America, the Caribbean and the Tasman Sea.32–33, 36

Fifth freedom traffic rights are sought by airlines wishing to take up unserved or underserved routes, or by airlines whose flights already make technical stops at a location as allowed by the second freedom.32 Governments (e.g. Thailand) may sometimes encourage fifth freedom traffic as a way of promoting tourism, by increasing the number of seats available. In turn, though, there may be reactionary pressure to avoid liberalizing traffic rights too much in order to protect a flag carrier's commercial interests.110 By the 1990s, fifth freedom traffic rights stirred controversy in Asia because of loss-making services by airlines in the countries hosting them.[19]16–19 Particularly in protest over US air carriers' service patterns in Asia, some nations have become less generous with regard to granting fifth freedom traffic rights, while sixth freedom traffic has grown in importance for Asian airlines.112

The Japan-United States bilateral air transport agreement of 1952 has been viewed as being particularly contentious because unlimited fifth freedom traffic rights have been granted to designated US air carriers serving destinations in the Asia Pacific region west of Japan. For example, in the early 1990s, the Japanese government's refusal to permit flights on the New York City—Osaka—Sydney route led to protests by the US government and the airlines that applied to serve that route. The Japanese government countered that about 10% of the traffic on the Japan—Australia sector was third and fourth freedom traffic to and from the US, while the bilateral agreement specified that primary justification for unlimited fifth freedom traffic was to fill up aircraft carrying a majority of US-originated or US-destined traffic under third and fourth freedom rights. Japan had held many unused fifth freedom traffic rights beyond the USA. However, these were seen as being less valuable than the fifth freedom traffic rights enjoyed by US air carriers via Japan, because of the higher operating costs of Japanese airlines and geographical circumstances. Japan serves as a useful gateway to Asia for North American travelers. The US contended that Japan's favourable geographical location and its flag airlines' carriage of a sizeable volume of sixth freedom traffic via gateway cities in Japan helped to level the playing field. In 1995, the air transport agreement was updated by way of liberalizing Japanese carriers' access to US destinations, while placing selected restrictions on US air carriers.19–24

Up until the 1980s, Air India's flights to New York JFK from India were all operated under fifth freedom rights. From its 1962 initiation of Boeing 707 service to Idlewild (renamed JFK in 1964) flights had intermediate stops at one Middle East airport (Kuwait, Cairo, or Beirut), then two or three European airports, the last of which was always London's Heathrow, with trans-Atlantic service operating between Heathrow and JFK. This service continued well into the Boeing 747 era. Currently, Air India's North American flights are nonstop Boeing 777 service to India, with one exception, that being a revival of fifth freedom flights operating Boeing 787 service on the Newark—Heathrow—Ahmedabad route.

Sixth freedom

[modifica | modifica wikitesto]The unofficial sixth freedom combines the third and fourth freedoms and is the right to carry passengers or cargo from a second country to a third country by stopping in one's own country.31 It can also be characterized as a form of the fifth freedom with an intermediate stop in the operating airline's home market. This characterization is often invoked as protectionist policy as the traffic, like fifth freedom traffic, is secondary in nature to third and fourth freedom traffic.[20]33–34 Consequently, some nations seek to regulate sixth freedom traffic as though it were fifth freedom traffic.130 China is an example of a country that restricts sixth freedom traffic from third party countries. Specifically, it is difficult for airlines to obtain permission from China to serve the country via codeshare flights from intermediate countries.[21]

Because the nature of air services agreements is essentially a mercantilist negotiation that strives for an equitable exchange of traffic rights the outcome of a bilateral agreement may not be fully reciprocal but rather a reflection of the relative size and geographic position of two markets, especially in the case of a large country negotiating with a much smaller one.[22]129 In exchange for a smaller state granting fifth freedom rights to a larger country, the smaller country may be able to intermediate sixth freedom traffic to onward destinations from the larger country.129–130

Seventh freedom

[modifica | modifica wikitesto]The unofficial seventh freedom is a variation of the fifth freedom. It is the right to carry passengers or cargo between two foreign countries without any continuing service to one's own country.31

On 2 October 2007, the United Kingdom and Singapore signed an agreement that allowed unlimited seventh freedom rights from 30 March 2018, along with a full exchange of other freedoms of the air.

Cabotage

[modifica | modifica wikitesto]Cabotage is the transport of goods or passengers between two points in the same country by a vessel or an aircraft registered in another country. Originally a shipping term, cabotage now covers aviation, railways, and road transport. It is "trade or navigation in coastal waters, or, the exclusive right of a country to operate the air traffic within its territory".[23]

Modified sixth freedom (indirect cabotage)

[modifica | modifica wikitesto]The unofficial modified sixth freedom is the right to carry passengers or cargo between two points in one foreign country, while making a stop in the home country.

For example, a Canadian carrier operating flights from a US airport, stopping in its Canadian hub, and to another US airport, is a modified sixth freedom flight.

Eighth freedom (consecutive cabotage)

[modifica | modifica wikitesto]The unofficial eighth freedom is the right to carry passengers or cargo between two or more points in one foreign country and is also known as cabotage.31 It is extremely rare outside Europe. The main example is the European Union, where such rights exist between all its member states. Other examples include the Single Aviation Market (SAM) established between Australia and New Zealand in 1996; the 2001 Protocol to the Multilateral Agreement on the Liberalization of International Air Transportation (MALIAT) between Brunei, Chile, New Zealand and Singapore; United Airlines "island hopper" route, from Guam to Honolulu, able to transport passengers within the Federated States of Micronesia and the Marshall Islands, although the countries involved are closely associated with the United States. Such rights have usually granted only where the domestic air network is very underdeveloped. A notable instance[senza fonte] was Pan Am's authority to fly between Frankfurt and West Berlin from the 1950s to 1980s, although political circumstances and not the state of the domestic air network dictated this – only airlines of the Allied Powers of France, the United Kingdom and the United States had the right to carry air traffic between West Germany and the occupied territory of West Berlin until 1990.[24] In 2005, the United Kingdom and New Zealand concluded an agreement granting unlimited cabotage rights.[25] Given the distance between the two countries, the agreement can be seen as reflecting a political principle rather than an expectation that these rights will be taken up in the near future. New Zealand had exchanged eighth-freedom rights with Ireland in 1999.[26]

Ninth freedom (stand alone cabotage)

[modifica | modifica wikitesto]The right to carry passengers or cargo within a foreign country without continuing service to or from one's own country,[27] sometimes known as "stand alone cabotage." It differs from the aviation definition of "true cabotage," in that it does not directly relate to one's own country.

See also

[modifica | modifica wikitesto]- Air rights

- Bilateral agreement

- Air transport agreement

- Freedom of movement

- Flight permits

Notes

[modifica | modifica wikitesto]^A Even when fifth freedom rights are in place further restrictions on capacity and frequency may result in an airline only using the rights for stopover traffic or not being able to carry any traffic at all.:131^A Even when fifth freedom rights are in place further restrictions on capacity and frequency may result in an airline only using the rights for stopover traffic or not being able to carry any traffic at all.Errore nelle note: </ref> di chiusura mancante per il marcatore <ref>131

References

[modifica | modifica wikitesto]- ^ Multilevel Regulation and the EU: The Interplay Between Global, European and National Normative Processes, The Netherlands, Brill, 2008, p. 187, ISBN 978-90-04-16438-3.

- ^ 4.1, in Manual on the Regulation of International Air Transport, 2nd, International Civil Aviation Organisation, 2004, ISBN 92-9194-404-1.

- ^ Erlinda M. Medalla (a cura di), 7: The airline industry, in Competition Policy In East Asia, New York, Routledge, 2005, pp. 145–169, ISBN 0415350751. URL consultato il 19 February 2013.

- ^ International Air Services Transit Agreement - list of signatory states. The document is not dated, but includes Kazakhstan, which notified the U.S. Secretary of State of its acceptance of the treaty in July 2007.

- ^ Luigi Vallero, The Freedom of Fifth Freedom Flights, in Airways, vol. 11, n. 102, Airways International Inc, August 2004, pp. 31–36.

- ^ International Air Services Transit Agreement (IASTA), Article 1, Section 1 Archiviato il January 6, 2016 Data nell'URL non combaciante: 6 gennaio 2016 in Internet Archive.

- ^ International Air Services Transit Agreement - list of signatory states (PDF), in International Civil Aviation Organization (archiviato dall'url originale il July 22, 2011). The document is not signed, but includes Kazakhstan, which notified the US Secretary of States of its acceptance of the treaty in July 2007.

- ^ P.P.C. Haanappel, 2, The transformation of sovereignty in the air, in Chia-Jui Cheng, Jiarui Cheng (a cura di), The Use of Air & Outer Space Cooperation & Competition:, London, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 1998, ISBN 9041105972. URL consultato il 20 February 2013.

- ^ Mulrine, Anna, Targeting the Enemy, US News and World Report, June 9, 2008.

- ^ IASTA, Article I, Section 4

- ^ Bijan Vasigh, Tom Tacker, Ken Fleming. Introduction to Air Transport Economics: From Theory to Applications. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2008. ISBN 0-7546-7081-3. On Google Books. Page 156

- ^ Overflight Fees (FAA)

- ^ Russia 'Blackmails' Lufthansa over Cargo Hubs retrieved June 5, 2008

- ^ David J.J Yang, 9, The New Dimension of Fifth Freedom: the conflict of interest between Asian and American airlines, in Chia-Jui Cheng, Jiarui Cheng (a cura di), The Use of Air & Outer Space Cooperation & Competition:, London, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 1998, ISBN 9041105972. URL consultato il 20 February 2013.

- ^ David Timothy Duvall, 5, Aeropolitics, global aviation networks and the regulation of international visitor flows, in Tim Coles, C. Michael Hall (a cura di), International Business and Tourism: Global Issues, Contemporary Interactions, New York, Routledge, 13 February 2008, ISBN 0203931033. URL consultato il 20 February 2013.

- ^ a b NoteA Errore nelle note: Tag

<ref>non valido; il nome "Note" è stato definito più volte con contenuti diversi - ^ Pablo Mendes de León, Cabotage in Air Transport Regulation, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 1992, ISBN 0792317955. URL consultato il 22 febbraio 2016.

- ^ David Rowell, Freedoms of the Air, in The Travel Insider, 12 novembre 2002. URL consultato il 25 novembre 2010.

- ^ Sumner J. La Croix, The Asia-Pacific Airline Industry: Economic Boom and Political Conflict, in East-West Center Special Reports, n. 4, October 1995. URL consultato il 20 February 2013.

- ^ H.A. Wassenbergh, Public International Air Transportation Law in a New Era, The Hague, Nijhoff, 1970, ISBN 9024750032. URL consultato il 22 febbraio 2016.

- ^ Asian Airlines' changing presence at London Heathrow Pt 1: Cathay and SIA increase capacity, in centreforaviation.com/, CAPA Centre for Aviation, 12 February 2013.

- ^ Pat Hanlon, Global Airlines, Routledge, 2012, ISBN 1136400737.

- ^ The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition

- ^ West Berlin#Air traffic

- ^ New Zealand Government: "Agreement allows unlimited UK flights" Archiviato il September 29, 2007 Data nell'URL non combaciante: 29 settembre 2007 in Internet Archive.

- ^ Minister Signs Air Agreement In Dublin, su beehive.govt.nz, 28 maggio 1999. URL consultato il 27 agosto 2012.

- ^ ICAO FAQ: Freedoms of the Air, su icao.int, International Civil Aviation Organisation. URL consultato il 10 June 2011.

External links

[modifica | modifica wikitesto]- ICAO Freedoms of the Air

- Multilateral Agreement on the Liberalization of International Air Transportation (MALIAT)

- Basic Position of Japanese Side in Japan-Us Passenger Air Talks (1996)

- boeing.com, http://www.boeing.com/resources/boeingdotcom/company/about_bca/pdf/StartupBoeing_Freedoms_of_the_Air.pdf.