Utente:Ptolemaios/Sandbox4

Si ritiene che l'accento greco antico sia stato di tipo musicale.

In greco antico una delle tre sillabe finali di una parola porta l'accento. Ogni sillaba contiene una vocale con una o due more, e una mora di una parola è accentata; la mora accentata è melodicamente più acuta rispetto alle altre.

L'accento non può risalire oltre la terzultima sillaba. Se l'ultima sillaba ha una vocale lunga, o è chiusa da due consonanti, l'accento non può risalire oltre la penultima sillaba; ma all'interno di queste limitazioni l'accento è libero..

Nei sostantivi l'accento è il più delle volte imprevedibile. Di solito l'accento si colloca il più indietro possibile rispettando le leggi di limitazioni, ad esempio πόλεμος pòlemos 'guerra' (queste parole hanno un accento detto recessivo) oppure è collocato sull'ultima mora, come in ποταμός potamòs 'fiume' (le parole di questo tipo sono dette ossitone). Ma in alcune parole come παρθένος parthènos '[ragazza] vergine', l'accento si colloca fra i due estremi.

Nei verbi l'accento è solitamente prevedibile e ha una funzione grammaticale piuttosto che lessicale, cioè differenzia le varie parti del verbo invece che vari verbi fra di loro. I modi finiti del verbo hanno in genere un accento recessivo, ma in certi participi, infiniti e imperativi non è recessivo.

Nel periodo classico (IV-V sec. a .C.) gli accenti non erano segnate nella scrittura, ma dal II sec. a.C. in poi furono inventati vari segni diacritici, inclusi l'accento acuto, circunflesso e grave, che indicavano rispettivamente il tono alto, il tono discendente e il tono basso o semibasso. Gli accenti grafici erano usati sporadicamente all'inizio e non entrarono nell'uso corrente fino al 600 a.C..

I frammenti sopravvissuti della musica greca, in particolare i due inni delfici incisi su una pietra di Delfi nel II sec.a.C., sembrano seguire molto strettamente gli accenti scritti sulle parole e possono essere usati per ricavare informazioni sulla realizzazione degli accenti.

Fra il II e il IV sec. a.C. la distinzione fra accento grave, acuto e cironflesso si perse e tutti e tre gli accenti iniziarono a essere pronunciati come accenti intensivi, generalmente sulla sillaba dove una volta c'era il tono alto.

Tipi di accento[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

I grammatici greci antichi indicavano l'accento con tre segni: l'accento acuto (ά), l'accento circonflesso (ᾶ) e l'accento grave (ὰ). L'accento acuto era quello più comune; si può trovare su ciascuna delle tre ultime sillabe della parola. Alcuni esempi:

- ἄνθρωπος ànthrōpos 'persona, essere umano'

- πολίτης polìtēs 'cittadino'

- ἀγαθός agathòs 'buono'

L'accento circonflesso, che rappresentava il tono discendente, si trova solo su vocali lunghe e dittonghi, e solo sulle ultime due sillabe di una parola:

- σῶμα sṑma 'corpo'

- γῆ ghḕ 'terra'

Quando un accento circonflesso si trova sulla sillaba finale di una parola polisillabica solitamente rappresenta l'esito di una contrazione:

- ποιῶ poiṑ 'faccio' (contratto da ποιέω poièō)

L'accento grave si trova, in sostituzione dell'acuto, solo sull'ultima sillaba di una parola. Quando una parola come ἀγαθός agathòs 'buono' con accento finale è seguita da una pausa (cioò quando si trova alla fine di una frase o di un verso)[1] o prima di un'enclitica come la forma debole di ἐστίν estìn 'è' (vedi oltre) l'accento è scritto acuto:

- ἀνὴρ ἀγαθός anḕr agathòs '[un] uomo buono'

- ἀνὴρ ἀγαθός ἐστιν anḕr agathòs estin 'è [un] uomo buono'

Tuttavia, quando la parola non si trova prima di una pausa o un'enclitica l'accento acuto è sostituito dal grave:

- ἀγαθὸς ἄνθρωπος agathòs ànthrōpos 'a good person'

Si ritiene generalmente che l'accento grave indichi l'assenza di elevazione della voce, oppure un tono meno acuto dell'accento acuto[2].

Terminologia[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Ci sono in tutto cinque possibilità di collocamento dell'accento. I termini usati dai grammatici greci per indicare i vari tipi di parole erano[3]:

- ossitona (ὀξύτονος): accento acuto sulla sillaba finale. Ad esempio: πατήρ 'padre'

- parossitona (παροξύτονος): accento acuto sulla penultima. Ad esempio: μήτηρ 'madre'

- proparossitona (προπαροξύτονος): accento acuto sulla terzultima. Ad esempio: ἄνθρωπος 'persona'

- perispomenona (περισπώμενος): accento circonflesso sull'ultima. Ad esempio: ὁρῶ 'vedo'

- properispomenona (προπερισπώμενος): accento circonflesso sulla penultima. Ad esempio: σῶμα 'corpo'

Una paroda baritona (βαρύτονος) indica una parola che non sia accentata sull'ultima sillaba, ossia alla terza, quarta e quinta delle possibilità descritte sopra[4].

Posizionamento dei segni di accento[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Se l'accento cade su un dittongo o su una vocale scritta con due vocali come ει l'accento si scrive sempre sulla seconda lettera, ad esempio[5]:

- τοῖς ναύταις tòis nàutais 'ai marinai'

- εἷς hḗs 'uno'

Quando una parola, come un nome proprio, inizia con la maiuscola l'accento e lo spirito si mettono prima della lettera. Se una parola inizia con un dittongo l'accento è scritto sulla seconda lettera. Ma in ᾍδης (o Ἅιδης) Hàdēs 'Ade', dove il dittongo è formato dallo iota sottoscritto (ossia ᾇ) si scrive davanti:

- Ἥρα Hḕrā 'Era'

- Αἴας Àiās 'Aiace'

- ᾍδης (o Ἅιδης) Hàdēs 'Ade'

Quando si combina con uno spirito l'accento circonflesso di mette sopra, mentre gli accenti acuti e gravi si mettono a destra degli spiriti, come negli esempi sopra. Quando un accento si combina con la dieresi, come in νηΐ nēì l'accento si mette sopra.

Coppie minime tonali[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Se, da una parte, è in larga parte prevedibile se l'accento su una determinata sillaba sia acuto o circonflesso, dall'altra ci sono casi in cui il cambio di accento su una vocale lunga indica un diverso significato; ad esempio:

- λύσαι lúsai 'che [egli] possa liberare' – λῦσαι lûsai 'liberare'

- οἴκοι oíkoi 'in casa' – οἶκοι oîkoi 'case'

- φώς phṓs 'uomo' (poetico) – φῶς phôs 'luce'

In altri casi ancora il significato cambia se l'accento si sposta su un'altra sillaba:

- πείθω peíthō 'io persuado' – πειθώ peithṓ 'persuasione'

- ποίησαι poíēsai 'fa'!' (imperativo medio) – ποιήσαι poiḗsai 'che [egli] possa fare' – ποιῆσαι poiêsai 'fare'

- μύριοι múrioi 'ten thousand' – μυρίοι muríoi 'countless'

- νόμος nómos 'legge' – νομός nomós 'pascolo'

- Ἀθήναιος Athḗnaios 'Ateneo' (nome proprio) – Ἀθηναῖος Athēnaîos 'ateniese'

C'è inoltre distinzione fra forme non accentate (o con accento grave) e parole accentate come:

- τις tis 'qualcuno' – τίς; tís? 'chi?'

- που pou 'da qualche parte' / 'presumo' – ποῦ; poû 'dove?'

- ἢ ḕ 'o' – ἦ ê 'in realtà' / 'ero' / '[egli] disse'

- ἀλλὰ allà 'ma' – ἄλλα álla 'altre cose'

- ἐστὶ estì 'è' – ἔστι ésti 'c'è' / 'esiste' / 'è possibile'Errore script: nessun modulo "Footnotes".

Storia dell'accento nella scrittura greca[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

I tre segni impiegati per indicare l'accento in greco antico, l'acuto (´), il circomflesso (῀) e il grave (`), sono attribuiti al filologo Aristofane di Bisanzio, che era a capo della celebre Biblioteca di Alessandria in Egitto all'inizio del II sec. a.C.Errore script: nessun modulo "Footnotes".. Il primo papiro che riporta segni di accento risale a questo periodo. Nei papiri gli accenti erano usati all'inizio solo sporadicamente, con lo scopo di aiutare i lettori a pronunciare correttamente la poesia greca e l'accento grave poteva essere usato su ogni vocale non accentata. Questi accenti erano utili, dal momento che il greco in questo periodo era scritto senza spazi fra le parole. Ad esempio, in un papiro la parola ὸρὲιχάλκωι òrèikhálkōi 'all'ottone' è scritta con accenti gravi sulle prime due sillabe, nel caso in cui il lettore leggesse erroneamente la prima sillaba come ὄρει órei 'a una montagna'Errore script: nessun modulo "Footnotes"..

Nei secoli seguenti vari altri grammatici scrissero sull'accentazione greca. Il più famoso di questi, Elio Erodiano, che visse e insegnò a Roma nel II sec. d.C., scrisse un lungo trattato in venti libri, diciannove dei quali dedicati all'accentazione. Sebbene il libro di Erodiano non ci sia giunto interamente, disponiamo di un'epitome (sintesi) redatta intorno al 400 d.C.Errore script: nessun modulo "Footnotes".. Un'altra testimonianza autorevole è quella di Apollonio DiscoloErrore script: nessun modulo "Footnotes"., padre di Erodiano.

I nomi di questi diacritici in italiano, e la parola "accento", derivano da calchi latini dei termini greci. Accentus in latino corrisponde al greco προσῳδία prosōidía "canto accompagnato da strumento, variazione di altezza nella voce"[6] (da questa parola deriva inoltre prosodia), acūtus a ὀξεῖα oxeîa "acuta",[7] gravis a βαρεῖα bareîa "pesante" o "grave",[8] e circumflexus a περισπωμένη perispōménē "tirata intorno" o "piegata"[9]. Le parole greche dei diacritici sono aggettivi femminili nominalizzati che in origine erano attributi di προσῳδία e quindi accordati al genere femminile.

I segni diacritici non erano usati nel periodo classico (V-IV sec. a.C.); furono gradualmente introdotti a partire dal II sec. d.C., ma nei manoscritti divennero cumuni soltanto dopo il VII secoloErrore script: nessun modulo "Footnotes"..

Origine dell'accento[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

L'accento greco antico, almeno nei sostantivi, sembra essere stato prevalentemente ereditato dalla lingua progenitrice dalla quale il greco e varie altre lingue europee e indiane derivano, il protoindoeuropeo. Ciò può essere osservato confrontando gli accenti in greco con quelli degli inni vedici (la più antica forma di sanscrito). Molto spesso sono gli stessi, ad esempio:[10]

- vedico pā́t, greco antico πούς 'piede' (nominativo)

- vedico pā́dam, greco antico πόδα 'piede' (accusativo)

- vedico padás, greco antico ποδός 'di piede' (genitivo)

- vedico padí, greco antico ποδί 'per piede' (dativo)

Ci sono inoltre altre corrispondenze di accento fra greco e vedico, ad esempio:Errore script: nessun modulo "Footnotes".

- vedico yugáṃ, greco antico ζυγόν zygón 'giogo'

- vedico áśvaḥ, greco antico ἵππος híppos 'cavallo'

- vedico śatáṃ, greco antico ἑκατόν hekatón '100'

- vedico návaḥ, greco antico νέος néos 'nuovo'

- vedico pitā́, greco antico πατήρ patḗr 'padre'

Una differenza fra il greco e il vedico, comunque, è che in greco l'accento può trovarsi solo su una delle ultime tre sillabe, mentre il vedico (e presumibilmente in protoindoeuropeo) poteva cadere su qualunque sillaba di una parola.

La distinzione in greco fra accento acuto e circonflesso sembra essere un'innovazione propria, e non è rintracciabile nell'indoeuropeo.Errore script: nessun modulo "Footnotes".

Pronuncia dell'accento[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Caratteristiche generali[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

È generalmente ritenuto che l'accento greco antico fosse principalmente musicale piuttosto che intensivo.[11]. Così, in una parola come ἄνθρωπος ánthrōpos 'essere umano, persona', la prima sillaba era pronunciata più acuta rispetto alle altre, ma non necessariamente più forte. Già nel XIX secolo si supponeva che in una parola con accento recessivo il tono acuto potesse cadere non improvvisamente, ma gradualmente in una sequenza alto-medio-basso, con l'ultimo elemento sempre breve[12].

Le prove di questo vengono da varie fonti. La prima sono le affermazioni dei gramamtici greci, che descrivono sempre l'accento in termini musicali, usando parole come ὀξύς oxýs 'acuto' e βαρύς barýs 'grave'.

Secondo Dionigi di Alicarnasso (I sec. d.C.), la melodia del parlato si estende per un intervallo 'di circa una quinta'. Questa affermazione è stata interpretata in diversi modi, ma si suppone generalmente che non si trattasse sempre costantemente di una quinta, ma che questa fosse l'intervallo massimo fra la sillaba acuta e quella grave. Si ritiene probabile che occasionalmente, soprattutto in fine di frase, l'intervallo fosse molto più piccolo[13]. Dionigi inoltre descrive come l'accento circonflesso combini il tono alto e il tono basso nella stessa sillaba, mentre con l'accento acuto i due toni si trovano su sillabe diverseErrore script: nessun modulo "Footnotes"..

Un'altra indicazione che l'accento fosse musicale è che nel periodo classico gli accenti delle parole sembrano non aver avuto nessun ruolo nella metrica poetica, diversamente da lingue come l'italiano che hanno un accento intensivoErrore script: nessun modulo "Footnotes".. Fu soltanto dal IV sec. d.C. che si iniziò a scrivere poesia impiegando l'accento (vedi oltre).

Tracce dalla musica[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Un importante segnale della natura melodica dell'accento greco viene dalle testimonianze musicali che ci sono pervenute, in particolare i due Inni delfici (II sec. a.C.), l'Epitaffio di Sicilo (I sec. d.C.) e gli inni di Mesomede di Creta (II sec. d.C.). Un esempio è la preghiera a Calliope e Apollo scritta da Mesomede, musicista di corte dell'imperatore Adriano:

Come si può vedere, le sillabe accentate hanno solitamente la nota più alta in una parola, sebbene talvolta le sillabe precedenti o seguenti sono comunque alte.

Quando l'accento è circonflesso la musica mostra spesso una caduta da una nota più alta a una più bassa all'interno della sillaba, esattamente come afferma Dionigi di Alicarnasso; esempi sono le parola Μουσῶν Mousôn 'delle muse' ed εὐμενεῖς eumeneîs 'benevolo' nella preghiera qui sopra. Tuttavia, a volte non c'è discesa nella stessa sillaba, ma il circonflesso sta su una singola nota, come in τερπνῶν terpnôn 'gradite' o Λατοῦς Latoûs 'di Latona' qui sopra.

Se l'accento è grave spesso il tono non subisce innalzamento, o a volte solo poco, come in σοφὲ sophè qui sopra.

Questa pratica greca di imitazione dei toni degli accenti nel canto musicale è molto vicina a varie lingue vive asiatiche o africane che hanno un accento tonale. Per questa ragione gli studiosi americani A.M. Devine e Laurence Stephens hanno sostenuto che questi innalzamenti e abbassamenti di tono che troviamo nella musica greca ci possano dare un'indicazione ragionevolmente precisa di ciò che accadeva nel parlatoErrore script: nessun modulo "Footnotes"..

In ogni caso, sembra però che la musica non seguisse sempre esattamente l'accentazione. Dionigi di Alicarnasso ci dà un esempio di musica scritta da Euripide per la tragedia Oreste. In questi versi che nelle edizioni moderne sono scritti σῖγα, σῖγα, λεπτὸν ἴχνος ἀρβύλας // τίθετε, μὴ κτυπεῖτ᾽ (sîga, sîga, leptòn íkhnos arbýlas // títhete, mḕ ktypeît') 'Silenzio, silenzio! Posate piano le suole delle scarpe, non battete!'[14], Dionigi riferisce che nelle prime tre parole e nell'ultima non c'era innalzamento del tono, mentre sia in ἀρβύλας arbýlas 'della scarpa' che in τίθετε títhete 'posate' una nota grave era seguita da due note più acute, nonostante l'accento sulla prima sillaba in τίθετε títhete[15].

Comunque, sebbene i frammenti di musica più antica presentino a volte incongruenze, gli Inni delfici in particolare sembrano mostrare una stretta relazione fra la musica e le parole accentate, con solo tre discrepanze su 180 parole analizzate[16]. Altri dettagli del modo in cui gli accenti venivano messi in musica verranno dati oltre. Da notare che negli esempi musicali l'altezza assoluta è convenzionale, risalente a una pubblicazione di Friedrich Bellermann del 1840. Nell'esecuzione l'altezza sarebbe stata più bassa di almeno una terza minoreErrore script: nessun modulo "Footnotes"..

Accento acuto[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Quando i segni delle note della musica greca sono trascritti in notazione moderna si può vedere come un accento acuto sia solitamente seguito da una discesa che talvolta si estende su due sillabe. Normalmente la discesa è piccola, come in θύγατρες thýgatres 'figlie', Ὄλυμπον Ólyumpon 'Olimpo' o ἔτικτε étikte 'partoriva' qui in basso. Talvolta invece il salto è più ampio, come in μέλψητε mélpsēte 'che voi cantiate' o νηνέμους nēnémous 'senza vento':

Prima dell'accento l'innalzamento è in media minore rispetto alla discesa seguenteErrore script: nessun modulo "Footnotes".. Talvolta c'è un salto da una nota più grave, come nella parola μειγνύμενος meignýmenos 'mescolando' dal secondo inno; più spesso c'è un innalzamento graduale, come in Κασταλίδος Kastalídos 'di Castalia', Κυνθίαν Kynthían 'Cinzia' o ἀνακίδναται anakídnatai 'diffonde verso l'alto':

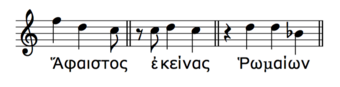

Tuttavia in certi casi prima di un accento invece di un innalzamento troviamo una stasi su una o due note della stessa altezza dell'accento, come in Παρνασσίδος Parnassídos 'di Parnasso', ἐπινίσεται epinísetai 'fa visita', Ῥωμαίων Rhōmaíōn 'dei Romani', o ἀγηράτῳ agērátōi 'senza età' dagli inni delfici:

L'anticipazione del tono alto di un accento in questo modo si ritrova anche in altre lingue tonali come alcune varietà di giapponese[17], turco[18] o serbo[19], dove ad esempio la parola papríka 'peperone' pronunciata pápríka. Non sarebbe quindi sorprendente se anche il greco avesse questa caratteristica. Devine e Stephens, tuttavia, citando l'affermazione di Dionigi secondo la quale una parola ha un solo tono alto, affermano che di norma le sillabe non accentate in greco fossero gravi[20].

Quando l'accento acuto si trova su una vocale lunga o su un dittongo si ritiene generalmente che il tono alto fosse sulla seconda mora della vocale, cioè che ci fosse un innalzamento del tono all'interno della sillabaErrore script: nessun modulo "Footnotes".Errore script: nessun modulo "Footnotes".. Talvolta la musica greca ci mostra esattamente questo, come nella parola αἴθει aíthei 'brucia' nel primo inno delfico, o φαίνου phaínou 'mostrati!' nell'epitaffio di Sicilo, o Σελάνα Selána 'luna' nell'Inno al sole, nel quale la sillaba acuta costruisce un melisma di due o tre note che salgono gradualmente.

Più spesso, invece, su una vocale lunga accentata nella musica non troviamo alcun innalzamento del tono e la sillaba resta su una nota della stessa altezza, come nelle parole Ἅφαιστος Hā́phaistos 'Efesto' dal primo inno delfico oppure ἐκείνας ekeínas 'quelle' o Ῥωμαίων Rhōmaíōn 'dei Romani' al secondo inno:

Poiché ciò è così comune, è possibile che almeno qualche volta il tono non si alzasse su una vocale lunga con accento acuto, bma rimanesse fermo. Un'altra considerazione è che sebbene gli antichi grammatici descrivessero sempre l'accento circonflesso come di "due toni" (δίτονος) o 'composto' (σύνθετος) o 'doppio' (διπλοῦς), non facevano simili osservazioni per l'accento acuto. Altri invece sembrano menzionare un "circonflesso invertito", che potrebbe riferirsi a questo tipo di accentoErrore script: nessun modulo "Footnotes"..

Assimilazione tonale[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Devine e Stephens notano che talvolta in fine di parola il tono risale ancora, come se accompagnasse o anticipasse l'accento della parola seguente. Chiamano questo fenomento "innalzamento secondario". Esempi sono ἔχεις τρίποδα ékheis trípoda 'hai un tripode' o μέλπετε δὲ Πύθιον mélpete dè Pýthion 'cantate il pizio' nel secondo inno delfico. Secondo Devine e Stephens, ciò "probabilmente riflette un autentico processo di assimilazione del tono nel parlato spontaneo"Errore script: nessun modulo "Footnotes"..

Nella stragrande maggioranza della musica il tono scende sulla sillaba immediatamente successiva all'accento acuto. Ci sono tuttavia delle eccezioni. Una situazione in cui questo può accadere è quando due parole sono unite in una stasi o semistasi, come nelle frasi ἵνα Φοῖβον hína Phoîbon 'cosicché Febo' (primo inno) e πόλει Κεκροπίᾳ pólei Kekropíāi 'nella città di Cecropia' nel secondo inno delfico:

L'assimilazione tonale o sandhi tonale fra toni vicini è comune nelle lingue tonali. Devine e Stephens, citando un fenomeno simile nella lingua nigeriana hausa, commentano: "Questa non è un'incongruenza, ma riflette una caratteristica dell'intonazione di frase nel parlato spontaneo."Errore script: nessun modulo "Footnotes"..

Accento circonflesso[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

L'accento circonflesso veniva scritto solo su vocali lunghe o dittonghi. In musica è solitamente posto su un melisma di due note, con la prima più alta della seconda. Così ad esempio nel primo inno delfico la parola Φοῖβον Phoîbon 'Febo' è posta sulle stesse note di θύγατρες thýgatres 'figlie' poco prima sulla stessa riga, con l'unica eccezione che le prime due note stanno sulla stessa sillaba invece che a cavallo di due sillabe. Esattamente come l'accento acuto, il circonflesso può essere preceduto sia da una nota alla stessa altezza, come in ᾠδαῖσι ōidaîsi 'con canti', o da un innalzamento, come in μαντεῖον manteîon 'oracolare':

Sembra quindi che l'accento circonflesso fosse pronunciato esattamente come l'acuto, con la differenza che la discesa avveniva solitamente all'interno della stessa sillabaErrore script: nessun modulo "Footnotes".. Ciò è chiaro dalla descrizione di Dionigi di Alicarnasso (vedi sopra), che ci riferisce che l'accento circonflesso era una giustapposizione di tono alto e di tono basso nella stessa sillaba, ed è suggerito dalla parola ὀξυβαρεῖα oxybareîa 'acuto-grave', che è uno dei nomi dati all'accento circonflesso nei tempi antichiErrore script: nessun modulo "Footnotes".. Un'altra descrizione era δίτονος dítonos 'di due toni'Errore script: nessun modulo "Footnotes"..

Un'altra prova della pronuncia dell'accento circonflesso è il fatto che quando due vocali si contraevano in una, se la prima aveva l'accento acuto il risultato era un accento circonflesso: ad esempio ὁρά-ω horá-ō 'vedo' è contratto in ὁρῶ horô con accento circonflesso che combina i due toni rispettivamente acuto e grave delle due vocali originarie.

Nella maggior parte degli esempi negli inni delfici l'accento circonflesso è posto su un melisma di due note. Tuttavia, negli inni di Mesomede, soprattutto nell'inno a Nemesi, è più comune trovare l'accento circonflesso su una singola nota. Devine e Stephens vedono in questo la perdita graduale nel tempo della distinzione fra acuto e circonflesso[21].

Uno dei punti in cui un accento circonflesso può stare su una singola nota è in frasi dove un sostantivo è unito a un genitivo o un aggettivo. Esempi sono μῆρα ταύρων mêra taúrōn (primo inno delfico) 'cosce di toro', Λατοῦς γόνε Latoûs góne 'figlio di Latona' (preghiera a Calliope e Apollo di Mesomede), γαῖαν ἅπασαν gaîan hápasan 'tutto quanto il mondo' (inno al sole di Mesomede). In queste frasi l'accento della seconda parola è più alto o alla stessa altezza di quello della prima parola, e proprio in frasi come ἵνα Φοῖβον hína Phoîbon menzionate in precedenza, la mancanza di discesa del tono sembra rappresentare una qualche sorta di assimilazione o sandhi tonale fra i due accenti:

Quando un accento circonflesso appare subito prima di una virgola ha regolarmente una sola nota nella musica, come in τερπνῶν terpnôn 'gradite' nell'Invocazione a Calliope di Mesomede mostrata sopra. Altri esempi sono κλυτᾷ klytâi 'famosa', ἰοῖς ioîs 'con frecce' nel secondo inno delfico, ζῇς zêis 'tu vivi' nell'epitaffio di Sicilo e θνατῶν thnatôn, ἀστιβῆ astibê e μετρεῖς metreîs nell'Inno a Nemesi di MesomedeErrore script: nessun modulo "Footnotes"..

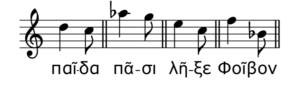

Un altro luogo in cui l'accento circonflesso ha talvolta una nota ferma nella musica è quando si trova sulla penultima sillaba di una parola, con la discesa che arriva solo nella sillaba seguente. Esempi sono παῖδα paîda, πᾶσι pâsi (primo inno delfico), λῆξε lêxe, σῷζε sôize e Φοῖβον Phoîbon (secondo inno delfico) e χεῖρα kheîra, πῆχυν pêkhyn (Inno a Nemesi).

Accento grave[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Il terzo segno di accento usato in greco antico è l'accento grave, il quale si trova solo sull'ultima sillaba di una parola, ad esempio ἀγαθὸς ἄνθρωπος agathòs ánthrōpos 'un uomo buono'. Gli studiosi sono divisi sul senso da attribuirgli; non è chiaro infatti se indichi che la parola debba essere completamente atona oppure se si tratti di un accento intermedio[22]. In alcuni documenti particolarmente antichi che fanno uso di accenti scritti l'accento grave poteva essere segnato su qualsisi sillaba che portasse il tono basso, non soltanto l'ultima di una parola, ad esempio ΘὲόδὼρὸςErrore script: nessun modulo "Footnotes"..

Alcuni studiosi, come il linguista russo Trubeckoj, hanno suggerito che, siccome di solito non c'è discesa dopo un accento grave, l'innalzamento di tono che si sente alla fine di una frase non era fonologicamente un vero accento, ma un semplice accento frasale generico come si può sentire in luganda[23]. Altri studiosi, invece, come Devine e Stephens, affermano al contrario che l'accento grave alla fine di una parola fosse un vero accento, ma che in certi contesti il suo tono fosse soppressoErrore script: nessun modulo "Footnotes"..

In musica una parola con accento grave spesso non è accentata affatto ed è posta su una nota ferma, come in questi esempi dal secondo inno delfico, ὃν ἔτικτε Λατὼ μάκαιρα hòn étikte Latṑ mákaira 'colui che Latona beata ha generato' e τότε λιπὼν Κυνθίαν νᾶσον tóte lipṑn Kynthían nâson 'quando, dopo aver lasciato l'isola cinzia', nei quali le parole Λατὼ Latṑ 'Latona' e λιπὼν lipṑn 'che ha lasciato' non presentano sillabe innalzate:

However, occasionally the syllable with the grave can be slightly higher than the rest of the word. This usually occurs when the word with a grave forms part of a phrase in which the music is in any case rising to an accented word, as in καὶ σοφὲ μυστοδότα Template:Grc-transl 'and you, wise initiator into the mysteries' in the Mesomedes prayer illustrated above, or in λιγὺ δὲ λωτὸς βρέμων, αἰόλοις μέλεσιν ᾠδὰν κρέκει Template:Grc-transl 'and the pipe, sounding clearly, weaves a song with shimmering melodies' in the 1st Delphic hymn:

In the Delphic hymns, a grave accent is almost never followed by a note lower than itself. However, in the later music, there are several examples where a grave is followed by a fall in pitch,Errore script: nessun modulo "Footnotes". as in the phrase below, 'the harsh fate of mortals turns' (Hymn to Nemesis), where the word χαροπὰ Template:Grc-transl 'harsh, grey-eyed' has a fully developed accent:Errore script: nessun modulo "Footnotes".

When an oxytone word such as ἀγαθός Template:Grc-transl 'good' comes before a comma or full stop, the accent is written as an acute. Several examples in the music illustrate this rise in pitch before a comma, for example Καλλιόπεια σοφά Template:Grc-transl 'wise Calliope' illustrated above, or in the first line of the Hymn to Nemesis ('Nemesis, winged tilter of the scales of life'):

There are almost no examples in the music of an oxytone word at the end of a sentence except the following, where the same phrase is repeated at the end of a stanza. Here the pitch drops and the accent appears to be retracted to the penultimate syllable:

This, however, contradicts the description of the ancient grammarians, according to whom a grave became an acute (implying that there was a rise in pitch) at the end of a sentence just as it does before a comma.[24]

General intonation[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Devine and Stephens also note that it is also possible from the Delphic hymns to get some indication of the intonation of Ancient Greek. For example, in most languages there is a tendency for the pitch to gradually become lower as the clause proceeds.Errore script: nessun modulo "Footnotes". This tendency, known as downtrend or downdrift, seems to have been characteristic of Greek too. For example, in the second line of the 1st Delphic Hymn, there is a gradual descent from a high pitch to a low one, followed by a jump up by an octave for the start of the next sentence. The words (Template:Grc-transl) mean: 'Come, so that you may hymn with songs your brother Phoebus, the Golden-Haired':

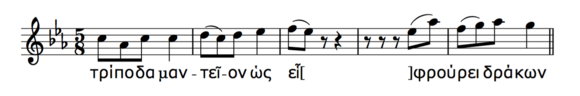

However, not all sentences follow this rule, but some have an upwards trend, as in the clause below from the first Delphic hymn, which when restored reads τρίποδα μαντεῖον ὡς εἷλ[ες ὃν μέγας ἐ]φρούρει δράκων Template:Grc-transl 'how you seized the prophetic tripod which the great snake was guarding'. Here the whole sentence rises up to the emphatic word δράκων Template:Grc-transl 'serpent':

In English before a comma, the voice tends to remain raised, to indicate that the sentence is not finished, and this appears to be true of Greek also. Immediately before a comma, a circumflex accent does not fall but is regularly set to a level note, as in the first line of the Seikilos epitaph, which reads 'As long as you live, shine! Do not grieve at all':

A higher pitch is also used for proper names and for emphatic words, especially in situations where a non-basic word-order indicates emphasis or focus.Errore script: nessun modulo "Footnotes". An example occurs in the second half of the Seikilos epitaph, where the last two lines read 'It is for a short time only that life exists; as for the end, Time demands it'. In the second sentence, where the order is object – subject – verb, the word χρόνος Template:Grc-transl 'time' has the highest pitch, as if emphasised:

Another circumstance in which no downtrend is evident is when a non-lexical word is involved, such as ἵνα Template:Grc-transl 'so that' or τόνδε Template:Grc-transl 'this'. In the music the accent in the word following non-lexical words is usually on the same pitch as the non-lexical accent, not lower than it.Errore script: nessun modulo "Footnotes". Thus there is no downtrend in phrases such as τόνδε πάγον Template:Grc-transl 'this crag' or ἵνα Φοῖβον Template:Grc-transl 'so that Phoebus', where in each case the second word is more important than the first:

Phrases containing a genitive, such as Λατοῦς γόνε Template:Grc-transl 'Leto's son' quoted above, or μῆρα ταύρων Template:Grc-transl 'thighs of bulls' in the illustration below from the first Delphic hymn, also have no downdrift, but in both of these the second word is slightly higher than the first:

Strophe and antistrophe[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

One problem which has been discussed concerning the relationship between music and word accent is what may have happened in choral music which was written in pairs of corresponding stanzas known as strophe and antistrophe. Rhythmically these always correspond exactly but the word accents in the antistrophe generally do not match those in the strophe.[25] Since none of the surviving music includes both a strophe and antistrophe, it is not clear whether the same music was written for both stanzas, ignoring the word accents in one or the other, or whether the music was similar but varied slightly to account for the accents. The following lines from Mesomedes' Hymn to the Sun,Errore script: nessun modulo "Footnotes". which are very similar but with slight variations in the first five notes, show how this might have been possible:

Change to modern Greek[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

In modern Greek the accent is for the most part in the same syllable of the words as it was in ancient Greek, but is one of stress rather than pitch, so that an accented syllable, such as the first syllable in the word ἄνθρωπος, can be pronounced sometimes on a high pitch, and sometimes on a low pitch. It is believed that this change took place around 2nd–4th century AD, at around the same time that the distinction between long and short vowels was also lost.Errore script: nessun modulo "Footnotes". One of the first writers to compose poetry based on a stress accent was the 4th-century Gregory of Nazianzus, who wrote two hymns in which syllable quantities play no part in the metre, but almost every line is accented on the penultimate syllable.[26]

In modern Greek there is no difference in pronunciation between the former acute, grave, and circumflex accents, and in the modern "monotonic" spelling introduced in Greek schools in 1982 only one accent is used, the acute, while monosyllables are left unaccented.[27]

Rules for the placement of the accent[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Law of Limitation[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

The accent may not come more than three syllables from the end of a word.

If an accent comes on the antepenultimate syllable, it is always an acute, for example:

- θάλασσα Template:Grc-transl 'sea'

- ἐποίησαν Template:Grc-transl 'they did'

- ἄνθρωπος Template:Grc-transl 'person'

- ἄνθρωποι Template:Grc-transl 'people'

- βούλομαι Template:Grc-transl 'I want'

Exception: ὧντινων Template:Grc-transl 'of what sort of', in which the second part is an enclitic word.Errore script: nessun modulo "Footnotes".

With a few exceptions, the accent can come on the antepenult only if the last syllable of the word is 'light'. The last syllable counts as light if it ends in a short vowel, or if it ends in a short vowel followed by no more than one consonant, or if the word ends in -οι Template:Grc-transl or -αι Template:Grc-transl, as in the above examples. But for words like the following, which have a heavy final syllable, the accent moves forward to the penultimate:

- ἀνθρώπου Template:Grc-transl 'of a man'

- ἀνθρώποις Template:Grc-transl 'for men'

- ἐβουλόμην Template:Grc-transl 'I wanted'

The ending -ει Template:Grc-transl always counts as long, and in the optative mood, the endings -οι Template:Grc-transl or -αι Template:Grc-transl also count as long and cause the accent to move forward in the same way:

- ποιήσει Template:Grc-transl 'he will do'

- ποιήσοι Template:Grc-transl 'he would do' (future optative)

The accent also cannot come on the antepenultimate syllable when the word ends in -ξ Template:Grc-transl or -ψ Template:Grc-transl,Errore script: nessun modulo "Footnotes". hence the difference in pairs of words such as the following:

- φιλόλογος Template:Grc-transl 'fond of words', but φιλοκόλαξ Template:Grc-transl 'fond of flatterers'

Exceptions, when the accent may remain on the antepenult even when the last vowel is long, are certain words ending in -ων Template:Grc-transl or -ως Template:Grc-transl, for example:Errore script: nessun modulo "Footnotes".

- πόλεως Template:Grc-transl 'of a city', πόλεων Template:Grc-transl 'of cities' (genitive)

- χρυσόκερως Template:Grc-transl 'golden-horned', ῥινόκερως Template:Grc-transl 'rhinoceros'

- ἵλεως Template:Grc-transl 'propitious',Errore script: nessun modulo "Footnotes". Μενέλεως Template:Grc-transl 'Menelaus'

σωτῆρα (Template:Grc-transl) Law[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

If the accent comes on the penultimate syllable, it must be a circumflex if the last two vowels of the word are long–short. This applies even to words ending in -ξ Template:Grc-transl or -ψ Template:Grc-transl:

- σῶμα Template:Grc-transl 'body'

- δοῦλος Template:Grc-transl 'slave'

- κῆρυξ Template:Grc-transl 'herald'

- λαῖλαψ Template:Grc-transl 'storm'

This rule is known as the σωτῆρα (Template:Grc-transl) Law, since in the accusative case the word σωτήρ Template:Grc-transl 'saviour' becomes σωτῆρα Template:Grc-transl.

In most cases, a final -οι Template:Grc-transl or -αι Template:Grc-transl counts as a short vowel:

- ναῦται Template:Grc-transl 'sailors'

- ποιῆσαι Template:Grc-transl 'to do'

- δοῦλοι Template:Grc-transl 'slaves'

Otherwise the accent is an acute:

- ναύτης Template:Grc-transl 'sailor'

- κελεύει Template:Grc-transl 'he orders'

- δούλοις Template:Grc-transl 'for slaves (dative)'

Exception 1: Certain compounds made from an ordinary word and an enclitic suffix have an acute even though they have long vowel–short vowel:Errore script: nessun modulo "Footnotes".

- οἵδε Template:Grc-transl 'these', ἥδε Template:Grc-transl 'this (fem.)' (but τῶνδε Template:Grc-transl 'of these')

- ὥστε Template:Grc-transl 'that (as a result)', οὔτε Template:Grc-transl 'nor'

- εἴθε Template:Grc-transl 'if only'

- οὔτις Template:Grc-transl 'no one' (but as a name in the Odyssey, Οὖτις Template:Grc-transl)[28]

Exception 2: In locative expressions and verbs in the optative mood a final -οι Template:Grc-transl or -αι Template:Grc-transl counts as a long vowel:

- οἴκοι Template:Grc-transl 'at home' (cf. οἶκοι Template:Grc-transl 'houses')

- ποιήσαι Template:Grc-transl 'he might do' (aorist optative, = ποιήσειε Template:Grc-transl) (cf. ποιῆσαι Template:Grc-transl 'to do')

Law of Persistence[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

The third principle of Greek accentuation is that, after taking into account the Law of Limitation and the σωτῆρα (Template:Grc-transl) Law, the accent in nouns, adjectives, and pronouns remains as far as possible on the same syllable (counting from the beginning of the word) in all the cases, numbers, and genders. For example:

- ζυγόν Template:Grc-transl 'yoke', pl. ζυγά Template:Grc-transl 'yokes'

- στρατιώτης Template:Grc-transl 'soldier', στρατιῶται Template:Grc-transl 'soldiers'

- πατήρ Template:Grc-transl, pl. πατέρες Template:Grc-transl 'fathers'

- σῶμα Template:Grc-transl, pl. σώματα Template:Grc-transl 'bodies'

But an extra syllable or a long ending causes accent shift:

- ὄνομα Template:Grc-transl, pl. ὀνόματα Template:Grc-transl 'names'

- δίκαιος Template:Grc-transl, fem. δικαίᾱ Template:Grc-transl 'just'

- σῶμα Template:Grc-transl, gen.pl. σωμάτων Template:Grc-transl 'of bodies'

Exceptions to the Law of Persistence[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

There are a number of exceptions to the Law of Persistence.

Exception 1: The following words have the accent on a different syllable in the plural:

- ἀνήρ Template:Grc-transl, pl. ἄνδρες Template:Grc-transl 'men'

- θυγάτηρ Template:Grc-transl, pl. θυγατέρες Template:Grc-transl (poetic θύγατρες Template:Grc-transl) 'daughters'

- μήτηρ Template:Grc-transl, pl. μητέρες Template:Grc-transl 'mothers'

The accusative singular and plural has the same accent as the nominative plural given above.

The name Δημήτηρ Template:Grc-transl 'Demeter' changes its accent to accusative Δήμητρα Template:Grc-transl, genitive Δήμητρος Template:Grc-transl, dative Δήμητρι Template:Grc-transl.

Exception 2: Certain vocatives (mainly of the 3rd declension) have recessive accent:

- Σωκράτης Template:Grc-transl, ὦ Σώκρατες Template:Grc-transl 'o Socrates'

- πατήρ Template:Grc-transl, ὦ πάτερ Template:Grc-transl 'o father'

Exception 3: All 1st declension nouns, and all 3rd declension neuter nouns ending in -ος Template:Grc-transl, have a genitive plural ending in -ῶν Template:Grc-transl. This also applies to 1st declension adjectives, but only if the feminine genitive plural is different from the masculine:

- στρατιώτης Template:Grc-transl 'soldier', gen.pl. στρατιωτῶν Template:Grc-transl 'of soldiers'

- τὸ τεῖχος Template:Grc-transl 'the wall', gen.pl. τῶν τειχῶν Template:Grc-transl 'of the walls'

Exception 4: Some 3rd declension nouns, including all monosyllables, place the accent on the ending in the genitive and dative singular, dual, and plural. (This also applies to the adjective πᾶς Template:Grc-transl 'all' but only in the singular.) Further details are given below.

- πούς Template:Grc-transl 'foot', acc.sg. πόδα Template:Grc-transl, gen.sg. ποδός Template:Grc-transl, dat.sg. ποδί Template:Grc-transl

Exception 5: Some adjectives, but not all, move the accent to the antepenultimate when neuter:

- βελτίων Template:Grc-transl 'better', neuter βέλτιον Template:Grc-transl

- But: χαρίεις Template:Grc-transl 'graceful', neuter χαρίεν Template:Grc-transl

Exception 6: The following adjective has an accent on the second syllable in the forms containing -αλ- Template:Grc-transl:

- μέγας Template:Grc-transl, pl. μεγάλοι Template:Grc-transl 'big'

Oxytone words[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Oxytone words, that is, words with an acute on the final syllable, have their own rules.

Change to a grave[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Normally in a sentence, whenever an oxytone word is followed by a non-enclitic word, the acute is changed to a grave; but before a pause (such as a comma, colon, full stop, or verse end), it remains an acute:

- ἀνὴρ ἀγαθός Template:Grc-transl 'a good man'

(Not all editors follow the rule about verse end.)Errore script: nessun modulo "Footnotes".

The acute also remains before an enclitic word such as ἐστί Template:Grc-transl 'is':

- ἀνὴρ ἀγαθός ἐστι Template:Grc-transl 'he's a good man'

In the words τίς; Template:Grc-transl 'who?' and τί; Template:Grc-transl 'what? why?', however, the accent always remains acute, even if another word follows:

- τίς οὗτος; Template:Grc-transl 'who is that?'

- τί ποιεῖς; Template:Grc-transl 'what are you doing?'

Change to a circumflex[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

When a noun or adjective is used in different cases, a final acute often changes to a circumflex. In the 1st and 2nd declension, oxytone words change the accent to a circumflex in the genitive and dative. This also applies to the dual and plural, and to the definite article:

- ὁ θεός Template:Grc-transl 'the god', acc.sg. τὸν θεόν Template:Grc-transl – gen. sg. τοῦ θεοῦ Template:Grc-transl 'of the god', dat.sg. τῷ θεῷ Template:Grc-transl 'to the god'

However, oxytone words in the 'Attic' declension keep their acute in the genitive and dative:[29]

- ἐν τῷ νεῴ Template:Grc-transl 'in the temple'

3rd declension nouns like βασιλεύς Template:Grc-transl 'king' change the acute to a circumflex in the vocative and dative singular and nominative plural:Errore script: nessun modulo "Footnotes".

- βασιλεύς Template:Grc-transl, voc.sg. βασιλεῦ Template:Grc-transl, dat.sg. βασιλεῖ Template:Grc-transl, nom.pl. βασιλεῖς Template:Grc-transl or βασιλῆς Template:Grc-transl

Adjectives of the type ἀληθής Template:Grc-transl 'true' change the acute to a circumflex in all the cases which have a long vowel ending:Errore script: nessun modulo "Footnotes".

- ἀληθής Template:Grc-transl, acc.sg. ἀληθῆ Template:Grc-transl, gen.sg. ἀληθοῦς Template:Grc-transl, dat.sg. ἀληθεῖ Template:Grc-transl, nom./acc.pl. ἀληθεῖς Template:Grc-transl, gen.pl. ἀληθῶν Template:Grc-transl

Adjectives of the type ἡδύς Template:Grc-transl 'pleasant' change the acute to a circumflex in the dative singular and nominative and accusative plural:Errore script: nessun modulo "Footnotes".

- ἡδύς Template:Grc-transl, dat.sg. ἡδεῖ Template:Grc-transl, nom./acc.pl. ἡδεῖς Template:Grc-transl

Accentless words[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

The following words have no accent, only a breathing:Errore script: nessun modulo "Footnotes".

- the forms of the article beginning with a vowel (ὁ, ἡ, οἱ, αἱ Template:Grc-transl)

- the prepositions ἐν Template:Grc-transl 'in', εἰς (ἐς) Template:Grc-transl 'to, into', ἐξ (ἐκ) Template:Grc-transl 'from'

- the conjunction εἰ Template:Grc-transl 'if'

- the conjunction ὡς Template:Grc-transl 'as, that' (also a preposition 'to')

- the negative adverb οὐ (οὐκ, οὐχ) Template:Grc-transl 'not'.

However, some of these words can have an accent when they are used in emphatic position. ὁ, ἡ, οἱ, αἱ Template:Grc-transl are written ὃ, ἣ, οἳ, αἳ when the meaning is 'who, which'; and οὐ Template:Grc-transl is written οὔ if it ends a sentence.

The definite article[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

The definite article in the nominative singular and plural masculine and feminine just has a rough breathing, and no accent:

- ὁ θεός Template:Grc-transl 'the god'

- οἱ θεοί Template:Grc-transl 'the gods'

Otherwise the nominative and accusative have an acute accent, which in the context of a sentence, is written as a grave:

- τὸν θεόν Template:Grc-transl 'the god' (accusative)

- τὰ ὅπλα Template:Grc-transl 'the weapons'

The genitive and dative (singular, plural and dual), however, are accented with a circumflex:

- τῆς οἰκίας Template:Grc-transl 'of the house' (genitive)

- τῷ θεῷ Template:Grc-transl 'for the god' (dative)

- τοῖς θεοῖς Template:Grc-transl 'for the gods' (dative plural)

- τοῖν θεοῖν Template:Grc-transl 'of/to the two goddesses' (genitive or dative dual)

1st and 2nd declension oxytones, such as θεός Template:Grc-transl, are accented the same way as the article, with a circumflex in the genitive and dative.

Nouns[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

1st declension[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Types[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Those ending in short -α Template:Grc-transl are all recessive:Errore script: nessun modulo "Footnotes".

- θάλασσα Template:Grc-transl 'sea', Μοῦσα Template:Grc-transl 'Muse (goddess of music)', βασίλεια Template:Grc-transl 'queen', γέφυρα Template:Grc-transl 'bridge', ἀλήθεια Template:Grc-transl 'truth', μάχαιρα Template:Grc-transl 'dagger', γλῶσσα Template:Grc-transl 'tongue, language'

Of those which end in long -α Template:Grc-transl or -η Template:Grc-transl, some have penultimate accent:

- οἰκία Template:Grc-transl 'house', χώρα Template:Grc-transl 'country', νίκη Template:Grc-transl 'victory', μάχη Template:Grc-transl 'battle', ἡμέρα Template:Grc-transl 'day', τύχη Template:Grc-transl 'chance', ἀνάγκη Template:Grc-transl 'necessity', τέχνη Template:Grc-transl 'craft', εἰρήνη Template:Grc-transl 'peace'

Others are oxytone:

- ἀγορά Template:Grc-transl 'market', στρατιά Template:Grc-transl 'army', τιμή Template:Grc-transl 'honour', ἀρχή Template:Grc-transl 'empire; beginning', ἐπιστολή Template:Grc-transl 'letter', κεφαλή Template:Grc-transl 'head', ψυχή Template:Grc-transl 'soul', βουλή Template:Grc-transl 'council'

A very few have a contracted ending with a circumflex on the last syllable:

- γῆ Template:Grc-transl 'earth, land', Ἀθηνᾶ Template:Grc-transl 'Athena', μνᾶ Template:Grc-transl 'mina (coin)'

Masculine 1st declension nouns usually have penultimate accent:

- στρατιώτης Template:Grc-transl 'soldier', πολίτης Template:Grc-transl 'citizen', νεανίας Template:Grc-transl 'young man', ναύτης Template:Grc-transl 'sailor', Πέρσης Template:Grc-transl 'Persian', δεσπότης Template:Grc-transl 'master', Ἀλκιβιάδης Template:Grc-transl 'Alcibiades', Μιλτιάδης Template:Grc-transl 'Miltiades'

A few, especially agent nouns, are oxytone:

- ποιητής Template:Grc-transl 'poet', κριτής Template:Grc-transl 'judge', μαθητής Template:Grc-transl 'learner, disciple', ἀθλητής Template:Grc-transl 'athlete', αὐλητής Template:Grc-transl 'piper'

There are also some with a contracted final syllable:

- Ἑρμῆς Template:Grc-transl 'Hermes', Βορρᾶς Template:Grc-transl 'the North Wind'

Accent movement[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

In proparoxytone words like θάλασσα Template:Grc-transl, with a short final vowel, the accent moves to the penultimate in the accusative plural, and in the genitive and dative singular, dual, and plural, when the final vowel becomes long:

- θάλασσα Template:Grc-transl 'sea', gen. τῆς θαλάσσης Template:Grc-transl 'of the sea'

In words with penultimate accent, the accent is persistent, that is, as far as possible it stays on the same syllable when the noun changes case. But if the last two vowels are long–short, it changes to a circumflex:

- στρατιώτης Template:Grc-transl 'soldier', nom.pl. οἱ στρατιῶται Template:Grc-transl 'the soldiers'

In oxytone words, the accent changes to a circumflex in the genitive and dative (also in the plural and dual), just as in the definite article:

- τῆς στρατιᾶς Template:Grc-transl 'of the army', τῇ στρατιᾷ Template:Grc-transl 'for the army'

All 1st declension nouns have a circumflex on the final syllable in the genitive plural:Errore script: nessun modulo "Footnotes".

- στρατιωτῶν Template:Grc-transl 'of soldiers', ἡμερῶν Template:Grc-transl 'of days'

The vocative of 1st declension nouns usually has the accent on the same syllable as the nominative. But the word δεσπότης Template:Grc-transl 'master' has a vocative accented on the first syllable:

- ὦ νεανία Template:Grc-transl 'young man!', ὦ ποιητά Template:Grc-transl 'o poet'

- ὦ δέσποτα Template:Grc-transl 'master!'Errore script: nessun modulo "Footnotes".

2nd declension[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Types[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

The majority of 2nd declension nouns have recessive accent, but there are a few oxytones, and a very few with an accent in between (neither recessive nor oxytone) or contracted:

- ἄνθρωπος Template:Grc-transl 'man', ἵππος Template:Grc-transl 'horse', πόλεμος Template:Grc-transl 'war', νῆσος Template:Grc-transl 'island', δοῦλος Template:Grc-transl 'slave', λόγος Template:Grc-transl 'wοrd', θάνατος Template:Grc-transl 'death', βίος Template:Grc-transl 'life', ἥλιος Template:Grc-transl 'sun', χρόνος Template:Grc-transl 'time', τρόπος Template:Grc-transl 'manner', νόμος Template:Grc-transl 'law, custom', θόρυβος Template:Grc-transl 'noise', κύκλος Template:Grc-transl 'circle'

- θεός Template:Grc-transl 'god', ποταμός Template:Grc-transl 'river', ὁδός Template:Grc-transl 'road', ἀδελφός Template:Grc-transl 'brother', ἀριθμός Template:Grc-transl 'number', στρατηγός Template:Grc-transl 'general', ὀφθαλμός Template:Grc-transl 'eye', οὐρανός Template:Grc-transl 'heaven', υἱός Template:Grc-transl 'son', τροχός Template:Grc-transl 'wheel'

- παρθένος Template:Grc-transl 'maiden', νεανίσκος Template:Grc-transl 'youth', ἐχῖνος Template:Grc-transl 'hedgehog; sea-urchin'

- νοῦς Template:Grc-transl 'mind' (contracted from νόος), πλοῦς Template:Grc-transl 'voyage'

Words of the 'Attic' declension ending in -ως Template:Grc-transl can also be either recessive or oxytone:[30]

- Μενέλεως Template:Grc-transl 'Menelaus', Μίνως Template:Grc-transl 'Minos'

- νεώς Template:Grc-transl 'temple', λεώς Template:Grc-transl 'people'

Neuter words are mostly recessive, but not all:

- δῶρον Template:Grc-transl 'gift', δένδρον Template:Grc-transl 'tree', ὅπλα Template:Grc-transl 'weapons', στρατόπεδον Template:Grc-transl 'camp', πλοῖον Template:Grc-transl 'boat', ἔργον Template:Grc-transl 'work', τέκνον Template:Grc-transl 'child', ζῷον Template:Grc-transl 'animal'

- σημεῖον Template:Grc-transl 'sign', μαντεῖον Template:Grc-transl 'oracle', διδασκαλεῖον Template:Grc-transl 'school'

- ζυγόν Template:Grc-transl 'yoke', ᾠόν Template:Grc-transl 'egg', ναυτικόν Template:Grc-transl 'fleet', ἱερόν Template:Grc-transl 'temple' (the last two are derived from adjectives)

Words ending in -ιον Template:Grc-transl often have penultimate accent, especially diminutive words:Errore script: nessun modulo "Footnotes".

- βιβλίον Template:Grc-transl 'book', χωρίον Template:Grc-transl 'place', παιδίον Template:Grc-transl 'baby', πεδίον Template:Grc-transl 'plain'

But some -ιον Template:Grc-transl words are recessive, especially those with a short antepenultimate:

- ἱμάτιον Template:Grc-transl 'cloak', στάδιον Template:Grc-transl 'stade' (600 feet), 'race-course', μειράκιον Template:Grc-transl 'lad'

Accent movement[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

As with the first declension, the accent on 2nd declension oxytone nouns such as θεός Template:Grc-transl 'god' changes to a circumflex in the genitive and dative (singular, dual, and plural):Errore script: nessun modulo "Footnotes".

- τοῦ θεοῦ Template:Grc-transl 'of the god', τοῖς θεοῖς Template:Grc-transl 'to the gods'

But those in the Attic declension retain their acute:Errore script: nessun modulo "Footnotes".

- τοῦ λεώ Template:Grc-transl 'of the people'

Unlike in the first declension, barytone words do not have a circumflex in the genitive plural:

- τῶν ἵππων Template:Grc-transl 'of the horses'

3rd declension[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Types[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

3rd declension masculine and feminine nouns can be recessive or oxytone:

- μήτηρ Template:Grc-transl 'mother', θυγάτηρ Template:Grc-transl 'daughter', φύλαξ Template:Grc-transl 'guard', πόλις Template:Grc-transl 'city', γέρων Template:Grc-transl 'old man', λέων Template:Grc-transl 'lion', δαίμων Template:Grc-transl 'god', τριήρης Template:Grc-transl 'trireme (warship)', μάρτυς Template:Grc-transl 'witness', μάντις Template:Grc-transl 'seer', τάξις Template:Grc-transl 'arrangement', Ἕλληνες Template:Grc-transl 'Greeks', Πλάτων Template:Grc-transl 'Plato', Σόλων Template:Grc-transl 'Solon', Δημοσθένης Template:Grc-transl

- πατήρ Template:Grc-transl 'father', ἀνήρ Template:Grc-transl 'man', γυνή Template:Grc-transl 'woman', βασιλεύς Template:Grc-transl 'king', ἱππεύς Template:Grc-transl 'cavalryman', χειμών Template:Grc-transl 'storm, winter', ἐλπίς Template:Grc-transl 'hope', Ἑλλάς Template:Grc-transl 'Greece', ἰχθύς Template:Grc-transl 'fish', πατρίς Template:Grc-transl 'fatherland', ἀγών Template:Grc-transl 'contest', λιμήν Template:Grc-transl 'harbour', χιών Template:Grc-transl 'snow', χιτών Template:Grc-transl 'tunic', ὀδούς Template:Grc-transl 'tooth', ἀσπίς Template:Grc-transl 'shield', δελφίς Template:Grc-transl 'dolphin', Ἀμαζών Template:Grc-transl 'Amazon', Ὀδυσσεύς Template:Grc-transl 'Odysseus', Σαλαμίς Template:Grc-transl 'Salamis', Μαραθών Template:Grc-transl 'Marathon'

Certain names resulting from a contraction are perispomenon:

- Ξενοφῶν Template:Grc-transl, Περικλῆς Template:Grc-transl, Ποσειδῶν Template:Grc-transl, Ἡρακλῆς Template:Grc-transl, Σοφοκλῆς Template:Grc-transl

Masculine and feminine monosyllables similarly can be recessive (with a circumflex) or oxytone (with an acute):

- παῖς Template:Grc-transl 'boy', ναῦς Template:Grc-transl 'ship', βοῦς Template:Grc-transl 'ox', γραῦς Template:Grc-transl 'old woman', ὗς Template:Grc-transl 'pig', οἶς Template:Grc-transl 'sheep'

- χείρ Template:Grc-transl 'hand', πούς Template:Grc-transl 'foot', νύξ Template:Grc-transl 'night', Ζεύς Template:Grc-transl 'Zeus', χθών Template:Grc-transl 'earth', μήν Template:Grc-transl 'month', Πάν Template:Grc-transl 'Pan', χήν Template:Grc-transl 'goose', αἴξ Template:Grc-transl 'goat'

3rd declension neuter nouns are all recessive, and monosyllables have a circumflex (this includes letters of the alphabet):[31]

- ὄνομα Template:Grc-transl 'name', σῶμα Template:Grc-transl 'body', στόμα Template:Grc-transl 'mouth', τεῖχος Template:Grc-transl 'wall', ὄρος Template:Grc-transl 'mountain', ἔτος Template:Grc-transl 'year', αἷμα Template:Grc-transl 'blood', ὔδωρ Template:Grc-transl 'water', γένος Template:Grc-transl 'race, kind', χρήματα Template:Grc-transl 'money', πρᾶγμα Template:Grc-transl 'business, affair', πνεῦμα Template:Grc-transl 'spirit, breath', τέλος Template:Grc-transl 'end'

- πῦρ Template:Grc-transl 'fire', φῶς Template:Grc-transl 'light', κῆρ Template:Grc-transl 'heart' (poetic)

- μῦ Template:Grc-transl, φῖ Template:Grc-transl, ὦ Template:Grc-transl 'omega'

Accent movement[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

The accent in the nominative plural and in the accusative singular and plural is usually on the same syllable as the nominative singular, unless this would break the three-syllable rule. Thus:

- χειμών Template:Grc-transl, pl. χειμῶνες Template:Grc-transl 'storms'

- γυνή Template:Grc-transl, pl. γυναῖκες Template:Grc-transl 'women'

- πατήρ Template:Grc-transl, pl. πατέρες Template:Grc-transl 'fathers'

- ναῦς Template:Grc-transl, pl. νῆες Template:Grc-transl 'ships'

- σῶμα Template:Grc-transl, pl. σώματα Template:Grc-transl 'bodies'

But, in accordance with the 3-syllable rule:

- ὄνομα Template:Grc-transl, nominative pl. ὀνόματα Template:Grc-transl 'names', gen. pl. ὀνομάτων Template:Grc-transl

The following are exceptions and have the accent on a different syllable in the nominative and accusative plural or the accusative singular:

- ἀνήρ Template:Grc-transl, pl. ἄνδρες Template:Grc-transl 'men'

- θυγάτηρ Template:Grc-transl, pl. θυγατέρες Template:Grc-transl (poetic θύγατρες Template:Grc-transl) 'daughters'

- μήτηρ Template:Grc-transl, pl. μητέρες Template:Grc-transl 'mothers'

But the following is recessive:

- Δημήτηρ Template:Grc-transl, acc. Δήμητρα Template:Grc-transl 'Demeter'

Words ending in -ευς Template:Grc-transl are all oxytone, but only in the nominative singular. In all other cases the accent is on the ε Template:Grc-transl or η Template:Grc-transl:

- βασιλεύς, βασιλέα, βασιλέως, βασιλεῖ Template:Grc-transl 'king', nom.pl. βασιλῆς Template:Grc-transl or βασιλεῖς Template:Grc-transl

Accent shift in genitive and dative[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

In 3rd declension monosyllables the accent usually shifts to the final syllable in the genitive and dative. The genitive dual and plural have a circumflex:

- singular: πούς, πόδα, ποδός, ποδί Template:Grc-transl 'foot'

dual: nom./acc. πόδε Template:Grc-transl, gen./dat. ποδοῖν Template:Grc-transl '(pair of) feet'

plural: πόδες, πόδας, ποδῶν, ποσί(ν) Template:Grc-transl 'feet' - singular: νύξ, νύκτα, νυκτός, νυκτί Template:Grc-transl 'night'

plural: νύκτες, νύκτας, νυκτῶν, νυξί(ν)

The following are irregular in formation, but the accent moves in the same way:

- ναῦς, ναῦν, νεώς, νηΐ Template:Grc-transl} 'ship'

plural: νῆες, νῆας, νεῶν, νηυσί(ν) Template:Grc-translErrore script: nessun modulo "Footnotes". - Ζεύς, Δία, Διός, Διΐ Template:Grc-transl 'Zeus'

The numbers for 'one', 'two', and 'three' also follow this pattern (see below).

γυνή Template:Grc-transl 'woman' and κύων Template:Grc-transl 'dog' despite not being monosyllables, follow the same pattern:

- γυνή, γυναῖκα, γυναικός, γυναικί Template:Grc-transl 'woman'

pl. γυναῖκες, γυναῖκας, γυναικῶν, γυναιξί(ν) Template:Grc-transl - κύων, κύνα, κυνός, κυνί Template:Grc-transl 'dog'

pl. κύνες, κύνας, κυνῶν, κυσί(ν) Template:Grc-translErrore script: nessun modulo "Footnotes".

There are some irregularities. The nouns παῖς Template:Grc-transl 'boy' and Τρῶες Template:Grc-transl 'Trojans' follow this pattern except in the genitive dual and plural:

- singular παῖς, παῖδα, παιδός, παιδί Template:Grc-transl 'boy'

παῖδες, παῖδας, παίδων, παισί(ν) Template:Grc-transl

The adjective πᾶς Template:Grc-transl 'all' has a mobile accent only in the singular:

- singular πᾶς, πάντα, παντός, παντί Template:Grc-transl

- plural πάντες, πάντας, πάντων, πᾶσι(ν) Template:Grc-transl.

Monosyllabic participles, such as ὤν Template:Grc-transl 'being', and the interrogative pronoun τίς; τί; Template:Grc-transl 'who? what?' have a fixed accent.Errore script: nessun modulo "Footnotes".

- singular ὤν, ὄντα, ὄντος, ὄντι Template:Grc-transl

- plural ὄντες, ὄντας, ὄντων, οὖσι(ν) Template:Grc-transl.

The words πατήρ Template:Grc-transl 'father', μήτηρ Template:Grc-transl 'mother', θυγάτηρ Template:Grc-transl 'daughter', have the following accentuation:

- πατήρ, πατέρα, πατρός, πατρί Template:Grc-transl 'father'

pl. πατέρες, πατέρας, πατέρων, πατράσι(ν) Template:Grc-translErrore script: nessun modulo "Footnotes".

γαστήρ Template:Grc-transl 'stomach' is similar:

- γαστήρ, γαστέρα, γαστρός, γαστρί Template:Grc-transl 'stomach'

pl. γαστέρες, γαστέρας, γάστρων, γαστράσι(ν) Template:Grc-transl}

The word ἀνήρ Template:Grc-transl 'man' has the following pattern, with accent shift in the genitive singular and plural:

- ἀνήρ, ἄνδρα, ἀνδρός, ἀνδρί Template:Grc-transl 'man'

pl. ἄνδρες, ἄνδρας, ἀνδρῶν, ἀνδράσι(ν) Template:Grc-transl

3rd declension neuter words ending in -ος Template:Grc-transl have a circumflex in the genitive plural, but are otherwise recessive:

- τεῖχος Template:Grc-transl 'wall', gen.pl. τειχῶν Template:Grc-transl 'of walls'

Concerning the genitive plural of the word τριήρης Template:Grc-transl 'trireme', there was uncertainty. 'Some people pronounce it barytone, others perispomenon,' wrote one grammarian.Errore script: nessun modulo "Footnotes".

Nouns such as πόλις Template:Grc-transl 'city' and ἄστυ Template:Grc-transl 'town' with genitive singular -εως Template:Grc-transl 'city' keep their accent on the first syllable in the genitive singular and plural, despite the long vowel ending:Errore script: nessun modulo "Footnotes".

- πόλις, πόλιν, πόλεως, πόλει Template:Grc-transl 'city'

pl. πόλεις, πόλεις, πόλεως, πόλεσι(ν) Template:Grc-transl

3rd declension neuter nouns ending in -ος Template:Grc-transl have a circumflex in the genitive plural, but are otherwise recessive:

- τεῖχος, τεῖχος, τείχους, τείχει Template:Grc-transl 'wall'

pl. τείχη, τείχη, τειχῶν, τείχεσι(ν) Template:Grc-transl

Vocative[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Usually in 3rd declension nouns the accent becomes recessive in the vocative:

- πάτερ Template:Grc-transl 'father!', γύναι Template:Grc-transl 'madam!', ὦ Σώκρατες Template:Grc-transl 'o Socrates', Πόσειδον Template:Grc-transl, Ἄπολλον Template:Grc-transl, Περίκλεις Template:Grc-translErrore script: nessun modulo "Footnotes".

However, the following have a circumflex on the final syllable:

- ὦ Ζεῦ Template:Grc-transl 'o Zeus', ὦ βασιλεῦ Template:Grc-transl 'o king'

Adjectives[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Types[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Adjectives frequently have oxytone accentuation, but there are also barytone ones, and some with a contracted final syllable. Oxytone examples are:

- ἀγαθός Template:Grc-transl 'good', κακός Template:Grc-transl 'bad', καλός Template:Grc-transl 'beautiful', δεινός Template:Grc-transl 'fearsome', Ἑλληνικός Template:Grc-transl 'Greek', σοφός Template:Grc-transl 'wise', ἰσχυρός Template:Grc-transl 'strong', μακρός Template:Grc-transl 'long', αἰσχρός Template:Grc-transl 'shameful', ὑψηλός Template:Grc-transl, μικρός Template:Grc-transl 'small', πιστός Template:Grc-transl 'faithful', χαλεπός Template:Grc-transl 'difficult'

- ἀριστερός Template:Grc-transl 'left-hand', δεξιτερός Template:Grc-transl 'right-hand'

- ἡδύς Template:Grc-transl 'pleasant', ὀξύς Template:Grc-transl 'sharp, high-pitched', βαρύς Template:Grc-transl 'heavy, low-pitched', ταχύς Template:Grc-transl 'fast', βραδύς Template:Grc-transl 'slow', βαθύς Template:Grc-transl 'deep', γλυκύς Template:Grc-transl 'sweet'. (The feminine of all of these has -εῖα Template:Grc-transl.)

- πολύς Template:Grc-transl 'much', plural πολλοί Template:Grc-transl 'many'

- ἀληθής Template:Grc-transl 'true', εὐτυχής Template:Grc-transl 'lucky', δυστυχής Template:Grc-transl 'unfortunate', ἀσθενής Template:Grc-transl 'weak, sick', ἀσφαλής Template:Grc-transl 'safe'

Recessive:

- φίλιος Template:Grc-transl 'friendly', πολέμιος Template:Grc-transl 'enemy', δίκαιος Template:Grc-transl 'just', πλούσιος Template:Grc-transl 'rich', ἄξιος Template:Grc-transl 'worthy', Λακεδαιμόνιος Template:Grc-transl 'Spartan', ῥᾴδιος Template:Grc-transl 'easy'

- μῶρος Template:Grc-transl 'foolish', ἄδικος Template:Grc-transl 'unjust', νέος Template:Grc-transl 'new, young', μόνος Template:Grc-transl 'alone', χρήσιμος Template:Grc-transl 'useful', λίθινος Template:Grc-transl 'made of stone', ξύλινος Template:Grc-transl 'wooden'

- ἄλλος Template:Grc-transl 'other', ἕκαστος Template:Grc-transl 'each'

- ὑμέτερος Template:Grc-transl 'your', ἡμέτερος Template:Grc-transl 'our'

- ἵλεως Template:Grc-transl 'propitious'

- εὐμένης Template:Grc-transl 'kindly', δυσώδης Template:Grc-transl 'bad-smelling', εὐδαίμων Template:Grc-transl 'happy'. (For other compound adjectives, see below.)

- πᾶς, πᾶσα, πᾶν Template:Grc-transl 'all', plural πάντες Template:Grc-transl

Paroxytone:

- ὀλίγος Template:Grc-transl 'little', ἐναντίος Template:Grc-transl 'opposite', πλησίος Template:Grc-transl 'near'

- μέγας Template:Grc-transl 'great, big', fem. μεγάλη Template:Grc-transl, plural μεγάλοι Template:Grc-transl

Properispomenon:

- Ἀθηναῖος Template:Grc-transl 'Athenian', ἀνδρεῖος Template:Grc-transl 'brave'

- ἑτοῖμος/ἕτοιμος Template:Grc-transl 'ready', ἐρῆμος/ἔρημος Template:Grc-transl 'deserted'

- τοιοῦτος Template:Grc-transl 'such', τοσοῦτος Template:Grc-transl 'so great'

Perispomenon:

- χρυσοῦς Template:Grc-transl 'golden', χαλκοῦς Template:Grc-transl 'bronze'

Comparative and superlative adjectives all have recessive accent:

- σοφώτερος Template:Grc-transl 'wiser', σοφώτατος Template:Grc-transl 'very wise'

- μείζων Template:Grc-transl 'greater', μέγιστος Template:Grc-transl 'very great'

Adjectives ending in -ής Template:Grc-transl have a circumflex in most of the endings, since these are contracted:Errore script: nessun modulo "Footnotes".

- ἀληθής Template:Grc-transl 'true', masculine plural ἀληθεῖς Template:Grc-transl

μῶρος Template:Grc-transl 'foolish' is oxytone in the New Testament:

- πέντε δὲ ἐξ αὐτῶν ἦσαν μωραί Template:Grc-transl 'and five of them were foolish' (Matthew 25.2)

Personal names derived from adjectives are usually recessive, even if the adjective is not:

- Ἀθήναιος Template:Grc-transl 'Athenaeus', from Ἀθηναῖος Template:Grc-transl 'Athenian'

- Γλαῦκος Template:Grc-transl, from γλαυκός Template:Grc-transl 'grey-eyed'

Accent movement[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Unlike in modern Greek, which has fixed accent in adjectives, an antepenultimate accent moves forward when the last vowel is long:

- φίλιος Template:Grc-transl 'friendly (masc.)', φιλίᾱ Template:Grc-transl 'friendly (fem.)', fem.pl. φίλιαι Template:Grc-transl

The genitive plural of feminine adjectives is accented -ῶν Template:Grc-transl, but only in those adjectives where the masculine and feminine forms of the genitive plural are different:

- πᾶς Template:Grc-transl 'all', gen.pl. πάντων Template:Grc-transl 'of all (masc.)', πασῶν Template:Grc-transl 'of all (fem.)'

But:

- δίκαιος Template:Grc-transl 'just', gen.pl. δικαίων Template:Grc-transl (both genders)

In a barytone adjective, in the neuter, when the last vowel becomes short, the accent usually recedes:

- βελτίων Template:Grc-transl 'better', neuter βέλτιον Template:Grc-transl

However, when the final -ν Template:Grc-transl was formerly *-ντ Template:Grc-transl, the accent does not recede (this includes neuter participles):Errore script: nessun modulo "Footnotes".Errore script: nessun modulo "Footnotes".

- χαρίεις Template:Grc-transl 'graceful', neuter χαρίεν Template:Grc-transl

- ποιήσας Template:Grc-transl 'having done', neuter ποιῆσαν Template:Grc-transl

The adjective μέγας Template:Grc-transl 'great' shifts its accent to the penultimate in forms of the word that contain lambda (λ Template:Grc-transl):

- μέγας Template:Grc-transl 'great', plural μεγάλοι Template:Grc-transl

The masculine πᾶς Template:Grc-transl 'all' and neuter πᾶν Template:Grc-transl have their accent on the ending in genitive and dative, but only in the singular:

- πᾶς Template:Grc-transl 'all', gen.sg. παντός Template:Grc-transl, dat.sg. παντί Template:Grc-transl (but gen.pl. πάντων Template:Grc-transl, dat.pl. πᾶσι Template:Grc-transl)

The participle ὤν Template:Grc-transl 'being', genitive ὄντος Template:Grc-transl, has fixed accent.

Elided vowels[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

When the last vowel of an oxytone adjective is elided, an acute (not a circumflex) appears on the penultimate syllable instead:Errore script: nessun modulo "Footnotes".

- δείν' ἐποίει Template:Grc-transl 'he was doing dreadful things' (for δεινά)

- πόλλ' ἀγαθά Template:Grc-transl 'many good things' (for πολλά)

This rule also applies to verbs and nouns:

- λάβ' ὦ ξένε Template:Grc-transl 'take (the cup), o stranger' (for λαβέ)

But it does not apply to minor words such as prepositions or ἀλλά Template:Grc-transl 'but':

- πόλλ' οἶδ' ἀλώπηξ, ἀλλ' ἐχῖνος ἓν μέγα Template:Grc-transl

'the fox knows many things, but the hedgehog one big thing' (Archilochus)

The retracted accent was always an acute. The story was told of an actor who, in a performance of Euripides' play Orestes, instead of pronouncing γαλήν᾽ ὁρῶ Template:Grc-transl 'I see a calm sea', accidentally said γαλῆν ὁρῶ Template:Grc-transl 'I see a weasel', provoking laughter in the audience and mockery the following year in Aristophanes' Frogs.[32]

Compound nouns and adjectives[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Ordinary compounds, that is, those which are not of the type 'object+verb', usually have recessive accent:

- ἱπποπόταμος Template:Grc-transl 'hippopotamus' ('horse of the river')

- Τιμόθεος Template:Grc-transl 'Timothy' ('honouring God')

- σύμμαχος Template:Grc-transl 'ally' ('fighting alongside')

- φιλόσοφος Template:Grc-transl 'philosopher' ('loving wisdom')

- ἡμίονος Template:Grc-transl 'mule' ('half-donkey')

But there are some which are oxytone:

- ἀρχιερεύς Template:Grc-transl 'high priest'

- ὑποκριτής Template:Grc-transl 'actor, hypocrite'

Compounds of the type 'object–verb', if the penultimate syllable is long or heavy, are usually oxytone:

- στρατηγός Template:Grc-transl 'general' ('army-leader')

- γεωργός Template:Grc-transl 'farmer' ('land-worker')

- σιτοποιός Template:Grc-transl 'bread-maker'

But 1st declension nouns tend to be recessive even when the penultimate is long:

- βιβλιοπώλης Template:Grc-transl 'book-seller'

- συκοφάντης Template:Grc-transl 'informer' (lit. 'fig-revealer')

Compounds of the type 'object+verb' when the penultimate syllable is short are usually paroxytone:

- βουκόλος Template:Grc-transl 'cowherd'

- δορυφόρος Template:Grc-transl 'spear-bearer'

- δισκοβόλος Template:Grc-transl 'discus-thrower'

- ἡμεροσκόπος Template:Grc-transl 'look-out man' (lit. 'day-watcher')

But the following, formed from ἔχω Template:Grc-transl 'I hold', are recessive:

- αἰγίοχος Template:Grc-transl 'who holds the aegis'

- κληροῦχος Template:Grc-transl 'holder of an allotment (of land)'

Adverbs[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Adverbs formed from barytone adjectives are accented on the penultimate, as are those formed from adjectives ending in -ύς Template:Grc-transl; but those formed from other oxytone adjectives are perispomenon:Errore script: nessun modulo "Footnotes".

- ἀνδρεῖος Template:Grc-transl 'brave', ἀνδρείως Template:Grc-transl 'bravely'

- δίκαιος Template:Grc-transl 'just', δικαίως Template:Grc-transl 'justly'

- ἡδύς Template:Grc-transl, 'pleasant', ἡδέως Template:Grc-transl 'with pleasure'

- καλός Template:Grc-transl, 'beautiful', καλῶς Template:Grc-transl 'beautifully'

- ἀληθής Template:Grc-transl, 'true', ἀληθῶς Template:Grc-transl 'truly'

Adverbs ending in -κις Template:Grc-transl have penultimate accent:Errore script: nessun modulo "Footnotes".

- πολλάκις Template:Grc-transl 'often'

Numbers[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

The first three numbers have mobile accent in the genitive and dative:Errore script: nessun modulo "Footnotes".

- εἷς Template:Grc-transl 'one (m.)', acc. ἕνα Template:Grc-transl, gen. ἑνός Template:Grc-transl 'of one', dat. ἑνί Template:Grc-transl 'to or for one'

- μία Template:Grc-transl 'one (f.)', acc. μίαν Template:Grc-transl, gen. μιᾶς Template:Grc-transl, dat. μιᾷ Template:Grc-transl

- δύο Template:Grc-transl 'two', gen/dat. δυοῖν Template:Grc-transl

- τρεῖς Template:Grc-transl 'three', gen. τριῶν Template:Grc-transl, dat. τρισί Template:Grc-transl

Despite the circumflex in εἷς Template:Grc-transl, the negative οὐδείς Template:Grc-transl 'no one (m.)' has an acute. It also has mobile accent in the genitive and dative:

- οὐδείς Template:Grc-transl 'no one (m.)', acc. οὐδένα Template:Grc-transl, gen. οὐδενός Template:Grc-transl 'of no one', dat. οὐδενί Template:Grc-transl 'to no one'

The remaining numbers to twelve are:Errore script: nessun modulo "Footnotes".

- τέσσαρες Template:Grc-transl 'four', πέντε Template:Grc-transl 'five', ἕξ Template:Grc-transl 'six', ἐπτά Template:Grc-transl 'seven', ὀκτώ Template:Grc-transl 'eight', ἐννέα Template:Grc-transl 'nine', δέκα Template:Grc-transl 'ten', ἕνδεκα Template:Grc-transl 'eleven' δώδεκα Template:Grc-transl 'twelve'

Also commonly found are:

- εἴκοσι Template:Grc-transl 'twenty', τριάκοντα Template:Grc-transl 'thirty', ἑκατόν Template:Grc-transl 'a hundred', χίλιοι Template:Grc-transl 'a thousand'.

Ordinals all have recessive accent, except those ending in -στός Template:Grc-transl:

- πρῶτος Template:Grc-transl 'first', δεύτερος Template:Grc-transl 'second', τρίτος Template:Grc-transl 'third' etc., but εἰκοστός Template:Grc-transl 'twentieth'

Pronouns[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

The personal pronouns are the following:[33]

- ἐγώ Template:Grc-transl 'I', σύ Template:Grc-transl 'you (sg.)', ἕ Template:Grc-transl 'him(self)'

- νῴ Template:Grc-transl 'we two', σφώ Template:Grc-transl 'you two'

- ἡμεῖς Template:Grc-transl 'we', ὑμεῖς Template:Grc-transl 'you (pl.)', σφεῖς Template:Grc-transl 'they'

The genitive and dative of all these personal pronouns has a circumflex, except for the datives ἐμοί Template:Grc-transl, σοί Template:Grc-transl, and σφίσι Template:Grc-transl:

- ἐμοῦ Template:Grc-transl 'of me', ὑμῖν Template:Grc-transl 'for you (pl.)', οἷ Template:Grc-transl 'to him(self)'

- ἐμοί Template:Grc-transl 'for me', σοί Template:Grc-transl 'for you', and σφίσι Template:Grc-transl 'for them(selves)'

The oblique cases of ἐγώ Template:Grc-transl, σύ Template:Grc-transl 'you (sg.)', ἕ Template:Grc-transl, and σφεῖς Template:Grc-transl can also be used enclitically when they are unemphatic (see below under Enclitics), in which case they are written without accents. When enclitic, ἐμέ Template:Grc-transl, ἐμοῦ Template:Grc-transl, and ἐμοί Template:Grc-transl are shortened to με Template:Grc-transl, μου Template:Grc-transl, and μοι Template:Grc-transl:

- ἔξεστί σοι Template:Grc-transl 'it is possible for you'

- εἰπέ μοι Template:Grc-transl 'tell me'

- νόμος γὰρ ἦν οὗτός σφισι Template:Grc-transl 'for this apparently was their custom' (Xenophon)

The accented form is usually used after a preposition:

- ἔπεμψέ με Κῦρος πρὸς σέ Template:Grc-transl 'Cyrus sent me to you'

- πρὸς ἐμέ Template:Grc-transl (sometimes πρός με Template:Grc-transl) 'to me'

The pronouns αὐτός Template:Grc-transl 'he himself', ἑαυτόν Template:Grc-transl 'himself (reflexive)', and ὅς Template:Grc-transl 'who, which' change the accent to a circumflex in the genitive and dative:

- αὐτόν Template:Grc-transl 'him', αὐτοῦ Template:Grc-transl 'of him, his', αὐτῷ Template:Grc-transl 'to him', αὐτοῖς Template:Grc-transl 'to them', etc.

Pronouns compounded with -δε Template:Grc-transl 'this' and -τις Template:Grc-transl are accented as if the second part was an enclitic word. Thus the accent of οἵδε Template:Grc-transl does not change to a circumflex even though the vowels are long–short:

- οἵδε Template:Grc-transl 'these', ὧντινων Template:Grc-transl 'of which things'

The demonstratives οὗτος Template:Grc-transl 'this' and ἐκεῖνος Template:Grc-transl 'that' are both accented on the penultimate syllable. But οὑτοσί Template:Grc-transl 'this man here' is oxytone.

When τίς Template:Grc-transl means 'who?' is it always accented, even when not before a pause. When it means 'someone' or 'a certain', it is enclitic (see below under Enclitics):

- πρός τινα Template:Grc-transl 'to someone'

- πρὸς τίνα; Template:Grc-transl 'to whom?'

The accent on τίς Template:Grc-transl is fixed and does not move to the ending in the genitive or dative.

Prepositions[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

ἐν Template:Grc-transl 'in', εἰς (ἐς) Template:Grc-transl 'to, into', and ἐκ (ἐξ) Template:Grc-transl 'from, out of' have no accent, only a breathing.

- ἐν αὐτῷ Template:Grc-transl 'in him'

Most other prepositions have an acute on the final when quoted in isolation (e.g. ἀπό Template:Grc-transl 'from', but in the context of a sentence this becomes a grave. When elided this accent does not retract and it is presumed that they were usually pronounced accentlessly:

- πρὸς αὐτόν Template:Grc-transl 'to him'

- ἀπ᾽ αὐτοῦ Template:Grc-transl 'from him'

When a preposition follows its noun, it is accented on the first syllable (except for ἀμφί Template:Grc-transl 'around' and ἀντί Template:Grc-transl 'instead of'):Errore script: nessun modulo "Footnotes".

- τίνος πέρι; Template:Grc-transl 'about what?'[34]

The following prepositions were always accented on the first syllable in every context:

- ἄνευ Template:Grc-transl 'without', μέχρι Template:Grc-transl 'until, as far as'

Interrogative words[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Interrogative words are almost all accented recessively. In accordance with the principle that in a monosyllable the equivalent of a recessive accent is a circumflex, a circumflex is used on a long-vowel monosyllable:

- πότε; Template:Grc-transl 'when?', πόθεν; Template:Grc-transl 'where from?', πότερον... ἢ...; Template:Grc-transl 'A... or B?', ποῖος; Template:Grc-transl 'what kind of?', πόσος; Template:Grc-transl 'how much?', πόσοι; Template:Grc-transl 'how many?'

- ἆρα...; Template:Grc-transl, ἦ...; Template:Grc-transl 'is it the case that...?'

- ποῦ; Template:Grc-transl 'where?', ποῖ; Template:Grc-transl 'where to?', πῇ; Template:Grc-transl 'which way?'

Two exceptions, with paroxytone accent, are the following:

- πηλίκος; Template:Grc-transl 'how big?', 'how old?', ποσάκις; Template:Grc-transl 'how often?'

The words τίς; Template:Grc-transl and τί; Template:Grc-transl always keep their acute accent even when followed by another word.[35] Unlike other monosyllables, they do not move the accent to the ending in the genitive or dative:

- τίς; Template:Grc-transl 'who? which?', τί; Template:Grc-transl 'what?', 'why?', τίνες; Template:Grc-transl 'which people?', τίνος; Template:Grc-transl 'of what? whose?', τίνι; Template:Grc-transl 'to whom?', τίνος πέρι; Template:Grc-transl 'about what?'

Some of these words, when accentless or accented on the final, have an indefinite meaning:

- τις Template:Grc-transl 'someone', τινὲς Template:Grc-transl 'some people', ποτε Template:Grc-transl 'once upon a time', etc.

When used in indirect questions, interrogative words are usually prefixed by ὁ- Template:Grc-transl or ὅς- Template:Grc-transl. The accentuation differs. The following are accented on the second syllable: