Utente:BlackPanther2013/Sandbox

- Utente:BlackPanther2013/Sandbox/parchi

- Utente:BlackPanther2013/Sandbox/citelli

- Utente:BlackPanther2013/Sandbox/rapaci

- Utente:BlackPanther2013/Sandbox/kakapo

- Utente:BlackPanther2013/Sandbox/Mata Atlantica

- Utente:BlackPanther2013/Sandbox/1.0

- Utente:BlackPanther2013/Sandbox/1

- Utente:BlackPanther2013/Sandbox/2

- Utente:BlackPanther2013/Sandbox/Global200

- Utente:BlackPanther2013/Sandbox/Caracal

- Utente:BlackPanther2013/Sandbox/felini

- Utente:BlackPanther2013/Sandbox/citelli

- Utente:BlackPanther2013/Sandbox/O.v.

- Utente:BlackPanther2013/Sandbox/S.m.

| Hydrobates | |

|---|---|

Uccelli delle tempeste europei | |

| Classificazione scientifica | |

| Dominio | Eukaryota |

| Regno | Animalia |

| Phylum | Chordata |

| Classe | Aves |

| Ordine | Procellariiformes |

| Famiglia | Hydrobatidae Mathews, 1912 |

| Genere | Hydrobates F. Boie, 1822 |

Gli Idrobatidi (Hydrobatidae Mathews, 1912), o uccelli delle tempeste boreali, sono una famiglia di uccelli marini appartenente all'ordine dei Procellariiformi, comprendente l'unico genere Hydrobates F. Boie, 1822. In passato in questo gruppo venivano inseriti anche gli uccelli delle tempeste australi, molto simili ad essi nell'aspetto ma non strettamente imparentati con loro, tanto che recentemente sono stati classificati in una famiglia a sé, gli Oceanitidi (Oceanitidae). Sono i più piccoli tra gli uccelli marini e si nutrono di crostacei planctonici e piccoli pesci che prelevano dalla superficie, generalmente mentre rimangono immobili a mezz'aria. Il loro volo è sfarfallante e talvolta ricorda quello di un pipistrello.

Come si intuisce dal nome, gli uccelli delle tempeste boreali vivono nell'emisfero boreale, anche se alcune specie che vivono intorno all'equatore possono spingersi anche più a sud. Sono uccelli rigorosamente pelagici e raggiungono la terraferma solo all'epoca della nidificazione. Della maggior parte delle specie conosciamo poco del comportamento e della distribuzione in mare, dove possono essere difficili da trovare e ancor più da identificare correttamente. Nidificano in colonie e mostrano una forte filopatria nei confronti delle colonie natali e dei siti di nidificazione. Quasi tutte le specie nidificano in fessure del terreno o in tane sotterranee e tutte tranne una frequentano le colonie riproduttive durante la notte. Le coppie formano legami monogami a lungo termine e condividono i compiti di incubazione e di alimentazione dei pulcini. Come quella di molti uccelli marini, la loro nidificazione è molto prolungata: la sola incubazione richiede fino a 50 giorni e l'involo sopraggiunge altri 70 giorni dopo.

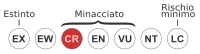

Diverse specie di uccelli delle tempeste sono minacciate dalle attività umane e si teme che una di esse, l'uccello delle tempeste di Guadalupe, sia già estinta. La principale minaccia per gli uccelli delle tempeste sono le specie introdotte, in particolare i mammiferi, nelle loro colonie riproduttive: molte popolazioni infatti erano solite nidificare su isole remote prive di mammiferi e non sono in grado di far fronte a predatori come ratti e gatti inselvatichiti.

Tassonomia[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

La famiglia Hydrobatidae venne introdotta, con Hydrobates come genere tipo dall'ornitologo australiano Gregory Mathews nel 1912.[1] Tale posizione però venne complicata dal fatto che la famiglia Hydrobatidae era già stata introdotta nel 1849 con Hydrobata come genere tipo dallo zoologo francese Côme-Damien Degland.[2] Hydrobata era stato istituito nel 1816 per classificare le specie della famiglia dei merli acquaioli, i Cinclidi, dall'ornitologo francese Louis Pierre Vieillot.[3] Nel 1992 il Codice internazionale di nomenclatura zoologica (ICZN) soppresse il genere Hydrobata Vieillot, 1816. Secondo le regole dell'ICZN, la validità della famiglia Hydrobatidae Degland, 1849 venne meno, dal momento che il genere tipo era stato soppresso. Ciò spianò quindi la strada alla famiglia Hydrobatidae introdotta nel 1912 da Mathews.[4]

Il genere Hydrobates venne istituito nel 1822 dallo zoologo tedesco Friedrich Boie.[5] In tale contesto elencò due specie, senza però specificare una specie tipo. Nel 1884 Spencer Baird, Thomas Brewer e Robert Ridgway designarono come specie tipo l'uccello delle tempeste europeo.[6][7] Il nome del genere combina il greco antico hudro-, «acqua», con batēs, «camminatore».[8]

In passato, all'interno di un'unica grande famiglia Hydrobatidae venivano riconosciute due sottofamiglie, gli Idrobatini (Hydrobatinae) e gli Oceanitini (Oceanitinae), ma l'analisi della sequenza del DNA del citocromo b ha suggerito che la famiglia fosse parafiletica e che fosse più corretto trattare i due gruppi come famiglie distinte.[9] Gli Oceanitidi (Oceanitidae), o uccelli delle tempeste australi, si trovano principalmente nell'emisfero australe (anche se l'uccello delle tempeste di Wilson migra regolarmente nell'emisfero boreale). Gli Idrobatidi, o uccelli delle tempeste boreali, sono limitati in gran parte all'emisfero boreale, anche se alcuni visitano o nidificano in regioni poco a sud dell'equatore.[10] Sono state rinvenute alcune specie fossili ascrivibili a questa famiglia, le più antiche delle quali risalgono al Miocene superiore.[9] Originariamente gli Idrobatidi venivano ripartiti in due generi, Hydrobates e Oceanodroma, ma nel 2021 l'Unione ornitologica internazionale (IOU) ha riunito tutte le specie nell'unico genere Hydrobates, poiché la famiglia è risultata essere parafiletica, come precedentemente stabilito.[11]

Il cladogramma seguente mostra i risultati dell'analisi filogenetica di Wallace et al. (2017).[12]

| Hydrobates |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Specie[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

| Nome comune | Nome scientifico | Stato di conservazione |

|---|---|---|

| Uccello delle tempeste europeo | Hydrobates pelagicus |

|

| Uccello delle tempeste codaforcuta del Pacifico | Hydrobates furcatus |

|

| Uccello delle tempeste di Hornby | Hydrobates hornbyi |

|

| Uccello delle tempeste di Swinhoe | Hydrobates monorhis |

|

| Uccello delle tempeste di Matsudaira | Hydrobates matsudairae |

|

| Uccello delle tempeste codaforcuta | Hydrobates leucorhous |

|

| Uccello delle tempeste di Townsend | Hydrobates socorroensis |

|

| Uccello delle tempeste di Ainley | Hydrobates cheimomnestes |

|

| Uccello delle tempeste cenerino | Hydrobates homochroa |

|

| Uccello delle tempeste di Castro | Hydrobates castro |

|

| Uccello delle tempeste di Monteiro | Hydrobates monteiroi |

|

| Uccello delle tempeste di Capo Verde | Hydrobates jabejabe |

|

| Uccello delle tempeste delle Galápagos | Hydrobates tethys |

|

| Uccello delle tempeste nero | Hydrobates melania |

|

| Uccello delle tempeste di Guadalupe | Hydrobates macrodactylus |

|

| Uccello delle tempeste di Markham | Hydrobates markhami |

|

| Uccello delle tempeste di Tristram | Hydrobates tristrami |

|

| Uccello delle tempeste minore | Hydrobates microsoma |

|

One species, the Guadalupe storm petrel (O. macrodactyla), is possibly extinct.

In 2010, the International Ornithological Congress (IOC) added the Cape Verde storm petrel (O. jabejabe) to their list of accepted species (AS) splits, following Bolton et al. 2007.[13] This species was split from the band-rumped storm petrel (O. castro). In 2016, the IOC added Townsend's storm petrel (O. socorroensis) and Ainley's storm petrel (O. cheimomnestes) to their list of AS splits, following Howell 2012. These species were split from Leach's storm petrel (O. leucorhoa).[11]

Morphology and flight[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Northern storm petrels are the smallest of all the seabirds, ranging in size from 13 to 25 cm in length. The Hydrobatidae have longer wings than the austral storm petrels, forked or wedge-shaped tails, and shorter legs. The legs of all storm petrels are proportionally longer than those of other Procellariiformes, but they are very weak and unable to support the bird's weight for more than a few steps.[9]

All but two of the Hydrobatidae are mostly dark in colour with varying amounts of white on the rump. Two species have different plumage entirely, the ringed storm petrel, which has white undersides and facial markings, and the fork-tailed storm petrel, which has pale grey plumage.[14] This is a notoriously difficult group to identify at sea. Onley and Scofield (2007) state that much published information is incorrect, and that photographs in the major seabird books and websites are frequently incorrectly ascribed as to species. They also consider that several national bird lists include species that have been incorrectly identified or have been accepted on inadequate evidence.[15]

Storm petrels use a variety of techniques to aid flight. Most species occasionally feed by surface pattering, holding and moving their feet on the water's surface while holding steady above the water. They remain stationary by hovering with rapid fluttering or using the wind to anchor themselves in place.[16] This method of feeding flight is more commonly used by Oceanitidae storm petrels, however. Northern storm petrels also use dynamic soaring, gliding across wave fronts gaining energy from the vertical wind gradient.[17][18]

Diet[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

The diet of many storm petrels species is poorly known owing to difficulties in researching; overall, the family is thought to concentrate on crustaceans.[19] Small fish, oil droplets, and molluscs are also taken by many species. Some species are known to be rather more specialised; the grey-backed storm petrel is known to concentrate on the larvae of goose barnacles.

Almost all species forage in the pelagic zone. Although storm petrels are capable of swimming well and often form rafts on the water's surface, they do not feed on the water. Instead, feeding usually takes place on the wing, with birds hovering above or "walking" on the surface (see morphology) and snatching small morsels. Rarely, prey is obtained by making shallow dives under the surface.[9]

Like many seabirds, storm petrels associate with other species of seabirds and marine mammal species to help obtain food. They may benefit from the actions of diving predators such as seals and penguins, which push prey up towards the surface while hunting, allowing the surface-feeding storm petrels to reach them.[20]

Distribution and movements[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

The Hydrobatidae are mostly found in the Northern Hemisphere.[19]

Several species of northern storm petrel undertake migrations after the breeding season, of differing lengths; long ones, such as Swinhoe's storm petrel, which breeds in the west Pacific and migrates to the west Indian Ocean;[21] or shorter ones, such as the black storm petrel, which nests in southern California and migrates down the coast of Central America as far south as Colombia.[22] Some species, like Tristram's storm petrel, are thought to be essentially sedentary and do not undertake any migrations away from their breeding islands.

Breeding[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Storm petrels nest colonially, for the most part on islands, although a few species breed on the mainland, particularly Antarctica. Nesting sites are attended at night to avoid predators;[23] the wedge-rumped storm petrels nesting in the Galapagos Islands are the exception to this rule and attend their nesting sites during the day.[24] Storm petrels display high levels of philopatry, returning to their natal colonies to breed. In one instance, a band-rumped storm petrel was caught as an adult 2 m from its natal burrow.[25] Storm petrels nest either in burrows dug into soil or sand, or in small crevices in rocks and scree. Competition for nesting sites is intense in colonies where storm petrels compete with other burrowing petrels, with shearwaters having been recorded killing storm petrels to occupy their burrows.[26] Colonies can be extremely large and dense, with densities as high as 8 pairs/m2 for band-rumped storm petrels in the Galapagos and colonies 3.6 million strong for Leach's storm petrel have been recorded.[27]

Storm petrels are monogamous and form long-term pair bonds that last a number of years. Studies of paternity using DNA fingerprinting have shown that, unlike many other monogamous birds, infidelity (extra-pair mating) is very rare.[28] As with the other Procellariiformes, a single egg is laid by a pair in a breeding season; if the egg fails, then usually no attempt is made to lay again (although it happens rarely). Both sexes incubate in shifts of up to six days. The egg hatches after 40 or 50 days; the young is brooded continuously for another 7 days or so before being left alone in the nest during the day and fed by regurgitation at night. Meals fed to the chick weigh around 10–20% of the parent's body weight, and consist of both prey items and stomach oil. Stomach oil is an energy-rich (its calorific value is around 9.6 kcal/g) oil created by partly digested prey in a part of the fore gut known as the proventriculus.[29] By partly converting prey items into stomach oil, storm petrels can maximise the amount of energy chicks receive during feeding, an advantage for small seabirds that can only make a single visit to the chick during a 24-hour period (at night).[30] The typical age at which chicks fledge depends on the species, taking between 50 and 70 days. The time taken to hatch and raise the young is long for the bird's size, but is typical of seabirds, which in general are K-selected, living much longer, delaying breeding for longer, and investing more effort into fewer young.[31] The young leave their burrows around 62 days. They are independent almost at once and quickly disperse into the ocean. They return to their original colony after 2 or 3 years, but will not breed until at least 4 years old. Storm petrels have been recorded living as long as 30 years.[32]

Threats and conservation[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Several species of storm petrel are threatened by human activities.[33] The Guadalupe storm petrel has not been observed since 1906 and most authorities consider it extinct. One species (the ashy storm petrel) is listed as endangered by the IUCN due to a 42% decline over 20 years.[34] For the ringed storm petrel, even the sites of their breeding colonies remain a mystery.

Storm petrels face the same threats as other seabirds; in particular, they are threatened by introduced species. The Guadalupe storm petrel was driven to extinction by feral cats,[35] and introduced predators have also been responsible for declines in other species. Habitat degradation, which limits nesting opportunities, caused by introduced goats and pigs is also a problem, especially if it increases competition from more aggressive burrowing petrels.

Cultural representation of the storm petrel[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

"Petrel" is a diminutive form of "Peter", a reference to Saint Peter; it was given to these birds because they sometimes appear to walk across the water's surface. The more specific "storm petrel" or "stormy petrel" is a reference to their habit of hiding in the lee of ships during storms.[36] Early sailors named these birds "Mother Carey's chickens" because they were thought to warn of oncoming storms; this name is based on a corrupted form of Mater Cara, a name for the Blessed Virgin Mary.[37]

Breton folklore holds that storm petrels are the spirits of sea-captains who mistreated their crew, doomed to spend eternity flying over the sea, and they are also held to be the souls of drowned sailors. A sailing superstition holds that the appearance of a storm petrel foretells bad weather.[38] Sinister names from Britain and France include waterwitch, satanite, satanique, and oiseau du diable.[39]

Symbol of revolution[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

The association of the storm petrel with turbulent weather has led to its use as a metaphor for revolutionary views,[40] the epithet "stormy petrel" being applied by various authors to characters as disparate as a Roman tribune,[41] a Presbyterian minister in the early Carolinas,[42] an Afghan governor,[43] or an Arkansas politician.[44] Russian revolutionary writer Maxim Gorky bore the epithet "the Stormy Petrel of the Revolution" (Буревестник Революции),[45][46] presumably due to his authorship of the famous 1901 poem "Song of the Stormy Petrel".

In "Song of the Stormy Petrel", Gorki turned to the imagery of subantarctic avifauna to describe Russian society's attitudes to the coming revolution. The storm petrel was depicted as unafraid of the coming storm –the revolution. This poem was called "the battle anthem of the revolution", and earned Gorky himself the title of the "Storm Petrel of the Revolution".[47][48] While this English translation of the bird's name may not be a very ornithologically accurate translation of the Russian burevestnik (буревестник),[49] it is poetically appropriate, as burevestnik literally means "the announcer of the storm". To honour Gorky and his work, the name Burevestnik was bestowed on a variety of institutions, locations, and products in the USSR.[40]

The motif of the stormy petrel has a long association with revolutionary anarchism. Various groups adopted the bird's name, either as a group identifier, as in the Spanish Civil War,[50] or for their publications. "Stormy Petrel" was the title of a German anarchist paper of the late 19th century; it was also the name of a Russian exile anarchist communist group operating in Switzerland in the early 20th century. The Stormy Petrel (Burevestnik) was the title of the magazine of the Anarchist Communist Federation in Russia around the time of the 1905 revolution,[51] and is still an imprint of the London group of the Anarchist Federation of Britain and Ireland.[52] Writing in 1936, Emma Goldman referred to Buenaventura Durruti as "this stormy petrel of the anarchist and revolutionary movement".

References[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

- ^ Gregory M. Mathews, The Birds of Australia, vol. 2, Londra, Witherby, 1912, p. 45.

- ^ (FR) Côme-Damien Degland, Ornithologie Européenne, ou Catalogue Analytique et Raisonné des Oiseaux Observés en Europe, vol. 1, Parigi, Libraire Encyclopédique de Robert, 1849, p. 445.

- ^ (FR) Louis Pierre Vieillot, Analyse d'une Nouvelle Ornithologie Élémentaire, Parigi, Deterville/self, 1816, p. 42.

- ^ Commission of the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature, Opinion 1696: Hydrobatidae Mathews, 1912 (1865) (Aves: Procellariiformes): conserved, in Bulletin of Zoological Nomenclature, vol. 49, n. 3, 1992, pp. 250-251.

- ^ (DE) Friedrich Boie, Ueber Classification, insonderheit der europäischen Vogel, in Isis von Oken, 1822, p. 562.

- ^ T. M. Brewer e R. Ridgway S. F. Baird, The Water Birds of North America, collana Memoirs of the Museum of Comparative Zoölogy, at Harvard College, Volume 13, vol. 2, Boston, Little, Brown, and Company, 1884, p. 403.

- ^ Ernst Mayr e G. William Cottrell (a cura di), Check-List of Birds of the World, vol. 1, 2ª ed., Cambridge, Massachusetts, Museum of Comparative Zoology, 1979, p. 111.

- ^ James A. Jobling, The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names, Londra, Christopher Helm, 2010, p. 196, ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- ^ a b c d C. Carboneras, Family Hydrobatidae (Storm petrels), in Handbook of Birds of the World, vol. 1, Barcellona, Lynx Edicions, 1992, pp. 258-265, ISBN 84-87334-10-5.

- ^ G. Nunn e S. Stanley, Body Size Effects and Rates of Cytochrome b evolution in tube-nosed seabirds (PDF), in Molecular Biology and Evolution, vol. 15, n. 10, 1998, pp. 1360-1371, DOI:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025864, PMID 9787440.

- ^ a b Frank Gill, David Donsker e Pamela Rasmussen (a cura di), Petrels, albatrosses, su IOC World Bird List Version 11.2, International Ornithologists' Union, luglio 2021. URL consultato il 15 gennaio 2022.

- ^ S. J. Wallace, J. A. Morris-Pocock, J. González-Solís, P. Quillfeldt e V. L. Friesen, A phylogenetic test of sympatric speciation in the Hydrobatinae (Aves: Procellariiformes), in Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, vol. 107, 2017, pp. 39-47, DOI:10.1016/j.ympev.2016.09.025, PMID 27693526.

- ^ Mark Bolton, Playback experiments indicate absence of vocal recognition among temporally and geographically separated populations of Madeiran Storm-petrels Oceanodroma castro, in Ibis, vol. 149, n. 2, 2007, pp. 255–263, DOI:10.1111/j.1474-919X.2006.00624.x.

- ^ Harrison, P. (1983) Seabirds, an identification guide Houghton Mifflin Company:Boston, ISBN 0-395-33253-2

- ^ Onley and Scofield, (2007) Albatrosses, Petrels and Shearwaters of the World. Helm, ISBN 978-0-7136-4332-9

- ^ Withers, P.C, Aerodynamics and Hydrodynamics of the 'Hovering' Flight of Wilson's Storm Petrel, in Journal of Experimental Biology, vol. 80, 1979, pp. 83–91, DOI:10.1242/jeb.80.1.83.

- ^ The flight of petrels and albatrosses (Procellariiformes), observed in South Georgia and its vicinity, in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B, vol. 300, n. 1098, 1982, pp. 75–106, DOI:10.1098/rstb.1982.0158.

- ^ Brinkley, E. & Humann, A. (2001) "Storm petrels" in The Sibley Guide to Bird Life and Behaviour (Elphick, C., Dunning J. & Sibley D. eds) Alfred A. Knopf:New York ISBN 0-679-45123-4

- ^ a b Brooke, M. (2004). Albatrosses and Petrels Across the World Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK ISBN 0-19-850125-0

- ^ Observations of Multispecies Seabird Flocks around South Georgia (PDF), in Auk, vol. 108, n. 4, 1991, pp. 801–810.

- ^ Barau's petrel Pterodroma baraui, Jouanin's petrel Bulweria fallax and other seabirds in the northern Indian Ocean in June–July 1984 and 1985 (PDF), in Ardea, vol. 79, 1990, pp. 1–14.

- ^ Ainley, D. G., and W. T. Everett. 2001. Black Storm Petrel (Oceanodroma melania). In The Birds of North America, No. 577 (A. Poole and F. Gill, eds.). The Birds of North America, Inc., Philadelphia, PA.

- ^ Effect of moon on activity of petrels (Class Aves) from the Selvagen Islands (Portugal), in Canadian Journal of Zoology, vol. 68, n. 7, 1990, pp. 1404–1409, DOI:10.1139/z90-209.

- ^ Ayala L, Sanchez-Scaglioni R, A new breeding location for Wedge-rumped Storm Petrels (Oceanodroma tethys kelsalli) in Peru, in Journal of Field Ornithology, vol. 78, n. 3, 2007, pp. 303–307, DOI:10.1111/j.1557-9263.2007.00106.x.

- ^ Harris, M., Survival and ages of first breeding of Galapagos seabirds (PDF), in Bird-Banding, vol. 50, n. 1, 1979, pp. 56–61, DOI:10.2307/4512409.

- ^ Ramos, J.A., Characteristics and competition of nest cavities in burrowing Procellariiformes (PDF), in Condor, vol. 99, n. 3, 1997, pp. 634–641, DOI:10.2307/1370475.

- ^ Habitat use and burrow densities of burrow-nesting seabirds on South East Island, Chatham Islands, New Zealand (PDF), in Notornis (Supplement), vol. 41, 1994, pp. 27–37.

- ^ Mauwk, T., Monogamy in Leach's Storm Petrel:DNA-fingerprinting evidence (PDF), in Auk, vol. 112, n. 2, 1995, pp. 473–482, DOI:10.2307/4088735.

- ^ Warham, J., The Incidence, Function and ecological significance of petrel stomach oils (PDF), in Proceedings of the New Zealand Ecological Society, vol. 24, 1976, pp. 84–93.

- ^ Stomach Oil and the Energy Budget of Wilson's Storm Petrel Nestlings (PDF), in Condor, vol. 95, n. 4, 1993, pp. 792–805, DOI:10.2307/1369418.

- ^ Schreiber, Elizabeth A. & Burger, Joanne.(2001.) Biology of Marine Birds, Boca Raton:CRC Press, ISBN 0-8493-9882-7

- ^ Klimkiewicz, M. K. 2007. Longevity Records of North American Birds Archiviato il 19 maggio 2011 in Internet Archive.. Version 2007.1. Patuxent Wildlife Research Center. Bird-Banding Laboratory. Laurel MD.

- ^ IUCN, 2006. Red List: Storm petrel Species Retrieved August 27, 2006.

- ^ Status and Trends of the Ashy Storm Petrel on Southeast Farallon Island, California, based upon capture-recapture analyses, in Condor, vol. 100, n. 3, 1998, pp. 438–447, DOI:10.2307/1369709.

- ^ A contemporary account of the decline of the Guadalupe Storm Petrel – The Present State of the Ornis of Guadaloupe Island (PDF), in Condor, vol. 10, n. 3, 1908, pp. 101–106, DOI:10.2307/1360977.

- ^ Slotterback, J. W. (2002). Band-rumped Storm Petrel (Oceanodroma castro) and Tristram’s Storm-Petrel (Oceanodroma tristrami). In The Birds of North America, No. 673 (A. Poole and F. Gill, eds.). The Birds of North America, Inc., Philadelphia, PA.

- ^ Craig Campbell, 'Miraculous' St Peter bird is able to walk on water, su sundaypost.com.

- ^ Eyers, Jonathan (2011). Don't Shoot the Albatross!: Nautical Myths and Superstitions. A&C Black, London, UK. ISBN 978-1-4081-3131-2.

- ^ Edward A. Armstrong, The Folklore of Birds, Dover, 1970, p. 213, ISBN 0-486-22145-8.

- ^ a b Margaret Ziolkowski, Literary Exorcisms of Stalinism: Russian Writers and the Soviet Past, Camden House, 1998.

- ^ Frank Frost Abbott, Society and Politics in Ancient Rome: Essays and Sketch, Biblo & Tannen Publishers, 1909.

- ^ Mary-Elizabeth Lynah, Archibald Stobo of Carolina: Presbyterianism's Stormy-petrel, American Historical Society, 1934.

- ^ C. Grey, European Adventurers of Northern India, 1785 to 1849, Atlantic Publishers & Distri, 1929, pp. 186, 190.; the person in question is Khaji Khan, Kakar (or Kakur), governor of Bamian

- ^ The life story of Jeff Davis: the stormy petrel of Arkansas politics, Parke-Harper publishing co., 1925.

- ^ See e.g. numerous references in this Cand. Sc. (Philology) dissertation abstract: Tatiana Petrovna (Леднева, Татьяна Петровна) Ledneva, Авторская позиция в произведениях М. Горького 1890-х годов. (Author's position in Maxim Gorky's 1890s works), 2002.

- ^ Dan Levin, Stormy Petrel: The Life and Work of Maxim Gorky, Schocken Books, 1965.

- ^ "A Legend Exhumed", review of "Stormy Petrel: The Life and Work of Maxim Gorky" by Dan Levin. Appleton-Century. Time Magazine, June 25, 1965

- ^ Mironov (2012) p. 461.

- ^ A 1903 edition of Vladimir Dal's Explanatory Dictionary of the Living Great Russian Language, would define burevestnik (the name of the bird used by Gorky's in Russian) or a "bird of storm" as a generic name for the Procellariidae, and would illustrate it with several examples, including the species known in English as the wandering albatross, southern giant petrel, northern fulmar, and European storm petrel. The actual Russian species name for the European storm petrel, according to the same dictionary, is kachurka, rather than an adjective phrase with burevestnik. See the entry Буря ("storm") in: (RU) Толковый словарь живого великорусского языка. В 4 тт. Т. 1: А—3 (Explanatory Dictionary of the Living Great Russian Language, in four volumes. Volume 4, A through Ze (in Cyrillic script), ОЛМА Медиа Групп, 2001, p. 172, ISBN 5-224-02354-8. (This is a modern reprint (using modernized Russian orthography) of the 1903 edition, which would have been familiar to Gorky and his readers).

- ^ Christie (2005) p. 43.

- ^ Yaroslansky (1937) Introduction.

- ^ Anarchist pamphlets/booklets, su afed.org.uk, Anarchists Federation.

| Moa | |

|---|---|

| |

| Stato di conservazione | |

| Classificazione scientifica | |

| Dominio | Eukaryota |

| Regno | Animalia |

| Phylum | Chordata |

| Classe | Aves |

| Infraclasse | Palaeognathae |

| Clade | Notopalaeognathae |

| Ordine | † Dinornithiformes Bonaparte, 1853[1] |

| Sinonimi | |

|

Dinornithes Gadow, 1893[2] | |

| Sottogruppi[3] | |

| |

I moa[N 1][4] (ordine Dinornithiformes) sono un gruppo estinto di uccelli incapaci di volare endemico della Nuova Zelanda.[5] Tra il Pleistocene superiore e l'Olocene ne vissero nove specie (ripartite in sei generi). Le due specie più grandi, Dinornis robustus e D. novaezelandiae, raggiungevano, con il collo esteso, circa 3,6 m di altezza e pesavano circa 230 kg,[6] mentre la più piccola, il moa di boscaglia (Anomalopteryx didiformis), aveva grosso modo le dimensioni di un tacchino.[7] Le stime indicano che quando i polinesiani si insediarono in Nuova Zelanda, intorno al 1300, vi fossero tra 58000[8] e circa 2,5 milioni di moa.[9]

I moa vengono generalmente classificati nel gruppo dei ratiti,[5] ma gli studi genetici hanno rivelato che i loro parenti più stretti siano i tinami dell'America meridionale, in grado di volare e in passato considerati un sister group dei ratiti.[10] Le nove specie di moa sono state gli unici uccelli non solo incapaci di volare, ma addirittura privi delle ali vestigiali presenti in tutti gli altri ratiti. Furono gli animali terrestri più grandi e gli erbivori dominanti nelle foreste, nelle boscaglie e negli ecosistemi subalpini della Nuova Zelanda fino all'arrivo dei māori: l'unico loro predatore era l'aquila di Haast. I moa scomparvero nel giro di cento anni dalla colonizzazione umana della Nuova Zelanda, soprattutto a causa della forte pressione venatoria.[8]

Etimologia[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

La parola moa è un termine polinesiano per indicare il pollame domestico. Il nome non era di uso comune tra i māori all'epoca del contatto con gli europei, probabilmente perché il tipo di uccelli che indicava era estinto da tempo e i racconti tradizionali a riguardo erano rari. Il nome venne registrato per la prima volta dai missionari William Williams e William Colenso nel gennaio 1838; Colenso ipotizzò che questi uccelli potessero somigliare a dei polli giganteschi. Nel 1912, il capo māori Urupeni Pūhara affermò che il nome tradizionaler del moa era te kura («uccello rosso»).[11]

Descrizione[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Gli scheletri di moa venivano tradizionalmente ricostruiti in posizione eretta per ricreare la loro altezza impressionante, ma l'analisi delle articolazioni vertebrali indica che probabilmente questi animali tenevano il collo rivolto in avanti,[12] in maniera simile al kiwi. La colonna vertebrale era collegata alla parte posteriore della testa, anziché alla base, indicando un allineamento orizzontale. Ciò avrebbe permesso loro di pascolare tra la vegetazione bassa, pur essendo in grado di alzare la testa e brucare tra le fronde degli alberi se necessario. Ciò ha portato a riconsiderare per difetto l'altezza dei moa più grandi. Tuttavia, le pitture rupestri māori raffigurano moa o uccelli dall'aspetto simile (probabilmente oche o becchi a rasoio) con il collo eretto, il che lascia ipotizzare che i moa erano in grado di far assumere al collo entrambe le posizioni.[13][14]

Non è giunta nessuna testimonianza sul tipo di suono emesso dai moa, ma è possibile farsi un'idea su quale fosse il loro richiamo dai resti fossili. La loro trachea era sorretta da molti piccoli anelli ossei noti come anelli tracheali. L'estrazione di questi anelli dagli scheletri articolati ha rivelato che almeno due generi di moa (Euryapteryx ed Emeus) presentavano un prolungamento tracheale: la loro trachea poteva raggiungere un metro di lunghezza e formava una grande ansa all'interno della cavità corporea.[12] Erano gli unici ratiti a presentare tale caratteristica, presente anche in molti altri gruppi di uccelli, tra cui cigni, gru e faraone. Questo aspetto è associato alla produzione di vocalizzazioni profonde e risonanti, udibili anche a grandi distanze.

Relazioni evolutive[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

I parenti più stretti dei moa sono i piccoli uccelli terricoli sudamericani chiamati tinami, che però sono capaci di volare.[10][15][16][17] In precedenza, si riteneva che fossero i kiwi, l'emù australiano e i casuari[18] i più stretti parenti dei moa.

Sebbene tra la fine del XIX secolo e l'inizio del XX secolo siano state descritte decine di specie, molte di queste si basavano su scheletri parziali e si sono rivelate sinonimi. Attualmente, vengono riconosciute più o meno ufficialmente undici specie, anche se studi recenti basati sull'analisi del DNA antico recuperato dalle ossa delle collezioni museali suggeriscono che all'interno di alcune di queste esistano lignaggi distinti. Un fattore che ha provocato molta confusione nella tassonomia dei moa è la variazione intraspecifica delle dimensioni delle ossa, correlata a periodi glaciali e interglaciali (cfr. regola di Bergmann e regola di Allen), nonché il dimorfismo sessuale manifesto di alcune specie. Sembra che Dinornis avesse il dimorfismo sessuale più pronunciato: le femmine erano alte fino al 150% e pesanti fino al 280% più dei maschi ed erano tanto più grandi da essere classificate come specie separate fino al 2003.[19][20] La questione è ancora più complicata per Euryapteryx curtus ed E. gravis: secondo uno studio del 2009 i due taxa erano sinonimi;[21] l'anno successivo, invece, altri studiosi hanno cercato di spiegare le differenze di dimensioni con il dimorfismo sessuale;[22] infine, nel 2012, uno studio morfologico ha indicato che fossero due distinte sottospecie.[23]

Le analisi del DNA antico hanno determinato che in diversi generi di moa si erano sviluppate diverse linee evolutive criptiche,[24] che avrebbero potuto portare alla nascita di distinte specie o sottospecie: Megalapteryx benhami (Archey) si è rivelato sinonimo di M. didinus (Owen), in quanto le ossa di entrambi condividono tutti i caratteri essenziali. Le differenze di dimensioni si possono spiegare con la presenza di una variazione clinale nord-sud combinata alla variazione temporale: i moa, infatti, erano più grandi durante l'otirano (l'ultimo periodo glaciale della Nuova Zelanda). Una variazione temporale simile è nota per il Pachyornis mappini dell'Isola del Nord.[25] Alcune delle altre variazioni di dimensioni possono essere probabilmente ricondotte a fattori geografici e temporali simili.[26]

I più antichi resti di moa provengono dalla fauna miocenica del giacimento di Saint Bathans, dove sono stati rinvenuti molteplici gusci d'uovo ed elementi degli arti posteriori, riconducibili a due specie già abbastanza grandi.[27]

Classificazione[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Tassonomia[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Attualmente vengono riconosciuti i seguenti generi e specie:[6]

- Ordine †Dinornithiformes (Gadow, 1893) Ridgway, 1901 [Dinornithes Gadow, 1893; Immanes Newton, 1884] (moa)

- Famiglia Dinornithidae Owen, 1843 [Palapteryginae Bonaparte, 1854; Palapterygidae Haast, 1874; Dinornithnideae Stejneger, 1884] (moa giganti)

- Genere Dinornis

- Moa gigante dell'Isola del Nord, Dinornis novaezealandiae (Isola del Nord)

- Moa gigante dell'Isola del Sud, Dinornis robustus (Isola del Sud)

- Genere Dinornis

- Famiglia Emeidae (Bonaparte, 1854) [Emeinae Bonaparte, 1854; Anomalopterygidae Oliver, 1930; Anomalapteryginae Archey, 1941] (moa minori)

- Genere Anomalopteryx

- Moa di boscaglia, Anomalopteryx didiformis (Isola del Nord e del Sud)

- Genere Emeus

- Moa orientale, Emeus crassus (Isola del Sud)

- Genere Euryapteryx

- Moa beccolargo, Euryapteryx curtus (Isola del Nord e del Sud)

- Genere Pachyornis

- Moa elefantino, Pachyornis elephantopus (Isola del Sud)

- Moa di Mantell, Pachyornis geranoides (Isola del Nord)

- Moa crestato, Pachyornis australis (Isola del Sud)[3]

- Genere Anomalopteryx

- Famiglia Megalapterygidae

- Genere Megalapteryx

- Moa degli altipiani, Megalapteryx didinus (Isola del Sud)

- Genere Megalapteryx

- Famiglia Dinornithidae Owen, 1843 [Palapteryginae Bonaparte, 1854; Palapterygidae Haast, 1874; Dinornithnideae Stejneger, 1884] (moa giganti)

Oltre a queste, sono note anche due specie ancora prive di nome rinvenute nel giacimento di Saint Bathans.[27]

Filogenesi[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Dal momento che i moa sono un gruppo di uccelli incapaci di volare privi di qualsiasi resto vestigiale di ossa delle ali, gli studiosi si sono da chiesti da sempre come fossero riusciti ad arrivare in Nuova Zelanda e da dove venissero. Esistono molte teorie riguardo all'arrivo e alla radiazione dei moa in Nuova Zelanda, ma quella più recente suggerisce che giunsero in Nuova Zelanda circa 60 milioni di anni fa e che si siano differenziati dalla forma basale (vedi sotto), Megalapteryx, circa 5,8 milioni di anni fa[28] e non 18,5 milioni di anni fa come ipotizzato da Baker et al. (2005). Ciò non significa necessariamente che non fosse avvenuta alcuna speciazione tra l'arrivo in Nuova Zelanda 60 milioni di anni fa e la separazione dalla forma basale 5,8 milioni di anni fa, ma che non sono ancora stati ritrovati resti fossili appartenenti alle più antiche linee evolutive di moa, che si estinsero prima della diversificazione di 5,8 milioni di anni fa.[29] La presenza di specie risalenti al Miocene indica con ogni certezza che la diversificazione dei moa abbia avuto inizio prima della divisione tra Megalapteryx e gli altri taxa.[27]

L'evento di massima sommersione dell'Oligocene (Oligocene Drowning Maximum), avvenuto circa 22 milioni di anni fa, quando solo il 18% dell'attuale Nuova Zelanda si trovava sopra il livello del mare, fu cruciale per la radiazione dei moa. Poiché la separazione dalla forma basale ebbe luogo così recentemente (5,8 milioni di anni fa), è stato ipotizzato che gli antenati delle linee evolutive di moa del Quaternario non avrebbero potuto essere presenti su quel che restava delle isole del Nord e del Sud durante la sommersione dell'Oligocene.[30] Ciò non implica che i moa fossero precedentemente assenti dall'Isola del Nord, che che solo quelli dell'Isola del Sud sopravvissero, in quanto solo l'Isola del Sud rimase sopra il livello del mare. Bunce et al. (2009) hanno ipotizzato che gli antenati dei moa sopravvissero sull'Isola del Sud e poi ricolonizzarono l'Isola del Nord circa due milioni di anni dopo, quando le due isole si collegarono nuovamente dopo essere rimaste separate per 30 milioni di anni.[20] La presenza di moa miocenici nella fauna di Saint Bathans sembra suggerire che questi uccelli siano aumentati di dimensioni subito dopo l'evento di sommersione dell'Oligocene, sempre che ne siano stati colpiti.[27]

Bunce et al. conclusero inoltre che la struttura altamente complessa del lignaggio dei Moa fu causata dalla formazione delle Alpi meridionali a circa 6 milioni di anni fa e dalla frammentazione dell'habitat su entrambe le isole derivante dai cicli glaciali del Pleistocene, dal vulcanismo e dai cambiamenti del paesaggio.[19] Il cladogramma sottostante è una filogenesi di Palaeognathae generata da Mitchell (2014)[15] con alcuni nomi di clade dopo Yuri et al. (2013).[30] Fornisce la posizione del moa (Dinornithiformes) nel contesto più ampio degli uccelli "dalla mascella antica" (Palaeognathae):

Bunce et al. conclusero inoltre che la struttura altamente complessa della linea evolutiva dei moa fu causata dalla formazione delle Alpi meridionali circa 6 milioni di anni fa e dalla frammentazione dell'habitat su entrambe le isole derivante dai cicli glaciali del Pleistocene, dal vulcanismo e dai cambiamenti del paesaggio.[20] Il cladogramma sottostante è una filogenesi di Palaeognathae prodotta da Mitchell (2014)[16] con alcuni nomi di clade tratti da Yuri et al. (2013).[31] Esso fornisce la posizione dei moa (Dinornithiformes) nel più ampio contesto degli uccelli «dalla mascella antica» (Palaeognathae):

| Palaeognathae |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Il cladogramma sottostante fornisce una filogenesi più dettagliata, a livello di specie, del ramo moa (Dinornithiformes) degli uccelli "antichi dalla mascella" (Palaeognathae) mostrati sopra

Il cladogramma sottostante fornisce una filogenesi più dettagliata, a livello di specie, della linea evolutiva dei moa (Dinornithiformes):[20]

| †Dinornithiformes |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Distribution and habitat[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Analyses of fossil moa bone assemblages have provided detailed data on the habitat preferences of individual moa species, and revealed distinctive regional moa faunas:[12][32][33][34][35][36][37]

South Island[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

The two main faunas identified in the South Island include:

- The fauna of the high-rainfall west coast beech (Nothofagus) forests that included Anomalopteryx didiformis (bush moa) and Dinornis robustus (South Island giant moa), and

- The fauna of the dry rainshadow forest and shrublands east of the Southern Alps that included Pachyornis elephantopus (heavy-footed moa), Euryapteryx gravis, Emeus crassus, and Dinornis robustus.

A 'subalpine fauna' might include the widespread D. robustus, and the two other moa species that existed in the South Island:

- Pachyornis australis, the rarest moa species, the only moa species not yet found in Māori middens. Its bones have been found in caves in the northwest Nelson and Karamea districts (such as Honeycomb Hill Cave), and some sites around the Wānaka district.

- Megalapteryx didinus, more widespread, named "upland moa" because its bones are commonly found in the subalpine zone. However, it also occurred down to sea level, where suitable steep and rocky terrain (such as Punakaiki on the west coast and Central Otago) existed. Their distributions in coastal areas have been rather unclear, but were present at least in several locations such as on Kaikōura, Otago Peninsula,[38] and Karitane.[39]

North Island[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Significantly less is known about North Island paleofaunas, due to a paucity of fossil sites compared to the South Island, but the basic pattern of moa-habitat relationships was the same.[12] The South Island and the North Island shared some moa species (Euryapteryx gravis, Anomalopteryx didiformis), but most were exclusive to one island, reflecting divergence over several thousand years since lower sea level in the Ice Age had made a land bridge across the Cook Strait.[12]

In the North Island, Dinornis novaezealandiae and Anomalopteryx didiformis dominated in high-rainfall forest habitat, a similar pattern to the South Island. The other moa species present in the North Island (Euryapteryx gravis, E. curtus, and Pachyornis geranoides) tended to inhabit drier forest and shrubland habitats. P. geranoides occurred throughout the North Island. The distributions of E. gravis and E. curtus were almost mutually exclusive, the former having only been found in coastal sites around the southern half of the North Island.[12]

Behaviour and ecology[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

About eight moa trackways, with fossilised moa footprint impressions in fluvial silts, have been found in the North Island, including Waikanae Creek (1872), Napier (1887), Manawatū River (1895), Marton (1896), Palmerston North (1911) (see photograph to left), Rangitīkei River (1939), and under water in Lake Taupō (1973). Analysis of the spacing of these tracks indicates walking speeds between 3 and 5 km/h (1.75–3 mph).[12]

Diet[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Their diet has been deduced from fossilised contents of their gizzards[40][41] and coprolites,[42] as well as indirectly through morphological analysis of skull and beak, and stable isotope analysis of their bones.[12] Moa fed on a range of plant species and plant parts, including fibrous twigs and leaves taken from low trees and shrubs. The beak of Pachyornis elephantopus was analogous to a pair of secateurs, and could clip the fibrous leaves of New Zealand flax (Phormium tenax) and twigs up to at least 8 mm in diameter.[41]

Moa filled the ecological niche occupied in other countries by large browsing mammals such as antelope and llamas.[43] Some biologists contend that a number of plant species evolved to avoid moa browsing.[43] Divaracating plants such as Pennantia corymbosa (the kaikōmako), which have small leaves and a dense mesh of branches, and Pseudopanax crassifolius (the horoeka or lancewood), which has tough juvenile leaves, are possible examples of plants that evolved in such a way.

Like many other birds, moa swallowed gizzard stones (gastroliths), which were retained in their muscular gizzards, providing a grinding action that allowed them to eat coarse plant material. These stones were commonly smooth rounded quartz pebbles, but stones over 110 millimetri (4 in) long have been found among preserved moa gizzard contents.[41] Dinornis gizzards could often contain several kilograms of stones.[12] Moa likely exercised a certain selectivity in the choice of gizzard stones and chose the hardest pebbles.[44]

Reproduction[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

The pairs of species of moa described as Euryapteryx curtus / E. exilis, Emeus huttonii / E. crassus, and Pachyornis septentrionalis / P. mappini have long been suggested to constitute males and females, respectively. This has been confirmed by analysis for sex-specific genetic markers of DNA extracted from bone material.[19]

For example, before 2003, three species of Dinornis were recognised: South Island giant moa (D. robustus), North Island giant moa (D. novaezealandiae), and slender moa (D. struthioides). However, DNA showed that all D. struthioides were males, and all D. robustus were females. Therefore, the three species of Dinornis were reclassified as two species, one each formerly occurring on New Zealand's North Island (D. novaezealandiae) and South Island (D. robustus);[19][45] D. robustus however, comprises three distinct genetic lineages and may eventually be classified as many species, as discussed above.

Examination of growth rings in moa cortical bone has revealed that these birds were K-selected, as are many other large endemic New Zealand birds.[18] They are characterised by having a low fecundity and a long maturation period, taking about 10 years to reach adult size. The large Dinornis species took as long to reach adult size as small moa species, and as a result, had fast skeletal growth during their juvenile years.[18]

No evidence has been found to suggest that moa were colonial nesters. Moa nesting is often inferred from accumulations of eggshell fragments in caves and rock shelters, little evidence exists of the nests themselves. Excavations of rock shelters in the eastern North Island during the 1940s found moa nests, which were described as "small depressions obviously scratched out in the soft dry pumice".[46] Moa nesting material has also been recovered from rock shelters in the Central Otago region of the South Island, where the dry climate has preserved plant material used to build the nesting platform (including twigs clipped by moa bills).[47] Seeds and pollen within moa coprolites found among the nesting material provide evidence that the nesting season was late spring to summer.[47]

Fragments of moa eggshell are often found in archaeological sites and sand dunes around the New Zealand coast. Thirty-six whole moa eggs exist in museum collections and vary greatly in size (from 120–240 millimetri (4,7–9,4 in) in length and 91–178 millimetri (3,6–7,0 in) wide).[48] The outer surface of moa eggshell is characterised by small, slit-shaped pores. The eggs of most moa species were white, although those of the upland moa (Megalapteryx didinus) were blue-green.[49]

A 2010 study by Huynen et al. found that the eggs of certain species were fragile, only around a millimetre in shell thickness: "Unexpectedly, several thin-shelled eggs were also shown to belong to the heaviest moa of the genera Dinornis, Euryapteryx, and Emeus, making these, to our knowledge, the most fragile of all avian eggs measured to date. Moreover, sex-specific DNA recovered from the outer surfaces of eggshells belonging to species of Dinornis and Euryapteryx suggest that these very thin eggs were likely to have been incubated by the lighter males. The thin nature of the eggshells of these larger species of moa, even if incubated by the male, suggests that egg breakage in these species would have been common if the typical contact method of avian egg incubation was used."[49] Despite the bird's extinction, the high yield of DNA available from recovered fossilised eggs has allowed the moa's genome to be sequenced.[50]

-

The skeleton of female upland moa with egg in unlaid position within the pelvic cavity in Otago Museum

-

An egg and embryo fragments of Emeus crassus

-

Restoration of an upland moa

Pre-human forests[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Studies of accumulated dried vegetation in the pre-human mid-late Holocene period suggests a low Sophora microphylla or Kōwai forest ecosystem in Central Otago that was used and perhaps maintained by moa, for both nesting material and food. Neither the forests nor moa existed when European settlers came to the area in the 1850s.[51]

Relationship with humans[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Extinction[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Before the arrival of humans, the moa's only predator was the massive Haast's eagle. New Zealand had been isolated for 80 million years and had few predators before human arrival, meaning that not only were its ecosystems extremely vulnerable to perturbation by outside species, but also the native species were ill-equipped to cope with human predators.[52][53] Polynesians arrived sometime before 1300, and all moa genera were soon driven to extinction by hunting and, to a lesser extent, by habitat reduction due to forest clearance. By 1445, all moa had become extinct, along with Haast's eagle, which had relied on them for food. Recent research using carbon-14 dating of middens strongly suggests that the events leading to extinction took less than a hundred years,[54] rather than a period of exploitation lasting several hundred years as previously hypothesised.

An expedition in the 1850s under Lieutenant A. Impey reported two emu-like birds on a hillside in the South Island; an 1861 story from the Nelson Examiner told of three-toed footprints measuring 36 cm (14 in) between Tākaka and Riwaka that were found by a surveying party; and finally in 1878, the Otago Witness published an additional account from a farmer and his shepherd.[55] An 80-year-old woman, Alice McKenzie, claimed in 1959 that she had seen a moa in Fiordland bush in 1887, and again on a Fiordland beach when she was 17 years old. She claimed that her brother had also seen a moa on another occasion.[56] In childhood, Mackenzie saw a large bird that she believed to be a takahē, but after its rediscovery in the 1940s, she saw a picture of it and concluded that she had seen something else.[57]

Some authors have speculated that a few Megalapteryx didinus may have persisted in remote corners of New Zealand until the 18th and even 19th centuries, but this view is not widely accepted.[58] Some Māori hunters claimed to be in pursuit of the moa as late as the 1770s; however, these accounts possibly did not refer to the hunting of actual birds as much as a now-lost ritual among South Islanders.[59] Whalers and sealers recalled seeing monstrous birds along the coast of the South Island, and in the 1820s, a man named George Pauley made an unverified claim of seeing a moa in the Otago region of New Zealand.[60][55] Occasional speculation since at least the late 19th century,[61][62] and as recently as 2008,[63] has suggested that some moa may still exist, particularly in the wilderness of South Westland and Fiordland. A 1993 report initially interested the Department of Conservation, but the animal in a blurry photograph was identified as a red deer.[64][65] Cryptozoologists continue to search for them, but their claims and supporting evidence (such as of purported footprints)[63] have earned little attention from experts and are pseudoscientific.[58]

The rediscovery of the takahē in 1948 after none had been seen since 1898 showed that rare birds can exist undiscovered for a long time. However, the takahē is a much smaller bird than the moa, and was rediscovered after its tracks were identified—yet no reliable evidence of moa tracks has ever been found, and experts still contend that moa survival is extremely unlikely, since they would have to be living unnoticed for over 500 years in a region visited often by hunters and hikers.[63]

Surviving remains[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Joel Polack, a trader who lived on the East Coast of the North Island from 1834 to 1837, recorded in 1838 that he had been shown "several large fossil ossifications" found near Mt Hikurangi. He was certain that these were the bones of a species of emu or ostrich, noting that "the Natives add that in times long past they received the traditions that very large birds had existed, but the scarcity of animal food, as well as the easy method of entrapping them, has caused their extermination". Polack further noted that he had received reports from Māori that a "species of Struthio" still existed in remote parts of the South Island.[66][67]

Dieffenbach[68] also refers to a fossil from the area near Mt Hikurangi, and surmises that it belongs to "a bird, now extinct, called Moa (or Movie) by the natives". 'Movie' is the first transcribed name for the bird.[69][70] In 1839, John W. Harris, a Poverty Bay flax trader who was a natural-history enthusiast, was given a piece of unusual bone by a Māori who had found it in a river bank. He showed the 15 cm (6 in) fragment of bone to his uncle, John Rule, a Sydney surgeon, who sent it to Richard Owen, who at that time was working at the Hunterian Museum at the Royal College of Surgeons in London.[55]

Owen puzzled over the fragment for almost four years. He established it was part of the femur of a big animal, but it was uncharacteristically light and honeycombed. Owen announced to a skeptical scientific community and the world that it was from a giant extinct bird like an ostrich, and named it Dinornis. His deduction was ridiculed in some quarters, but was proved correct with the subsequent discoveries of considerable quantities of moa bones throughout the country, sufficient to reconstruct skeletons of the birds.[55]

In July 2004, the Natural History Museum in London placed on display the moa bone fragment Owen had first examined, to celebrate 200 years since his birth, and in memory of Owen as founder of the museum.

Since the discovery of the first moa bones in the late 1830s, thousands more have been found. They occur in a range of late Quaternary and Holocene sedimentary deposits, but are most common in three main types of site: caves, dunes, and swamps.

Bones are commonly found in caves or tomo (the Māori word for doline or sinkhole, often used to refer to pitfalls or vertical cave shafts). The two main ways that the moa bones were deposited in such sites were birds that entered the cave to nest or escape bad weather, and subsequently died in the cave and birds that fell into a vertical shaft and were unable to escape. Moa bones (and the bones of other extinct birds) have been found in caves throughout New Zealand, especially in the limestone/marble areas of northwest Nelson, Karamea, Waitomo, and Te Anau.

Moa bones and eggshell fragments sometimes occur in active coastal sand dunes, where they may erode from paleosols and concentrate in 'blowouts' between dune ridges. Many such moa bones antedate human settlement, although some originate from Māori midden sites, which frequently occur in dunes near harbours and river mouths (for example the large moa hunter sites at Shag River, Otago, and Wairau Bar, Marlborough).

Densely intermingled moa bones have been encountered in swamps throughout New Zealand. The most well-known example is at Pyramid Valley in north Canterbury,[71] where bones from at least 183 individual moa have been excavated, mostly by Roger Duff of Canterbury Museum.[72] Many explanations have been proposed to account for how these deposits formed, ranging from poisonous spring waters to floods and wildfires. However, the currently accepted explanation is that the bones accumulated slowly over thousands of years, from birds that entered the swamps to feed and became trapped in the soft sediment.[73]

Many New Zealand and international museums hold moa bone collections. Auckland War Memorial Museum – Tāmaki Paenga Hira has a significant collection, and in 2018 several moa skeletons were imaged and 3D scanned to make the collections more accessible.[74] There is also a major collection in Otago Museum in Dunedin.

Feathers and soft tissues[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Several remarkable examples of moa remains have been found which exhibit soft tissues (muscle, skin, feathers), that were preserved through desiccation when the bird died in a naturally dry site (for example, a cave with a constant dry breeze blowing through it). Most of these specimens have been found in the semiarid Central Otago region, the driest part of New Zealand. These include:

- Dried muscle on bones of a female Dinornis robustus found at Tiger Hill in the Manuherikia River Valley by gold miners in 1864[75] (currently held by Yorkshire Museum)

- Several bones of Emeus crassus with muscle attached, and a row of neck vertebrae with muscle, skin, and feathers collected from Earnscleugh Cave near the town of Alexandra in 1870[76] (currently held by Otago Museum)

- An articulated foot of a male D. giganteus with skin and foot pads preserved, found in a crevice on the Knobby Range in 1874[77] (currently held by Otago Museum)

- The type specimen of Megalapteryx didinus found near Queenstown in 1878[75] (currently held by Natural History Museum, London; see photograph of foot on this page)

- The lower leg of Pachyornis elephantopus, with skin and muscle, from the Hector Range in 1884;[58][77] (currently held by the Zoology Department, Cambridge University)

- The complete feathered leg of a M. didinus from Old Man Range in 1894[78] (currently held by Otago Museum)

- The head of a M. didinus found near Cromwell sometime before 1949[79] (currently held by the Museum of New Zealand).

Two specimens are known from outside the Central Otago region:

- A complete foot of M. didinus found in a cave on Mount Owen near Nelson in the 1980s[80] (currently held by the Museum of New Zealand)

- A skeleton of Anomalopteryx didiformis with muscle, skin, and feather bases collected from a cave near Te Anau in 1980.[81]

In addition to these specimens, loose moa feathers have been collected from caves and rock shelters in the southern South Island, and based on these remains, some idea of the moa plumage has been achieved. The preserved leg of M. didinus from the Old Man Range reveals that this species was feathered right down to the foot. This is likely to have been an adaptation to living in high-altitude, snowy environments, and is also seen in the Darwin’s rhea, which lives in a similar seasonally snowy habitat.[12]

Moa feathers are up to 23 cm (9 in) long, and a range of colours has been reported, including reddish-brown, white, yellowish, and purplish.[12] Dark feathers with white or creamy tips have also been found, and indicate that some moa species may have had plumage with a speckled appearance.[82]

Potential revival[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

The creature has frequently been mentioned as a potential candidate for revival by cloning. Its iconic status, coupled with the facts that it only became extinct a few hundred years ago and that substantial quantities of moa remains exist, mean that it is often listed alongside such creatures as the dodo as leading candidates for de-extinction.[83] Preliminary work involving the extraction of DNA has been undertaken by Japanese geneticist Ankoh Yasuyuki Shirota.[84][85]

Interest in the moa's potential for revival was further stirred in mid-2014 when New Zealand Member of Parliament Trevor Mallard suggested that bringing back some smaller species of moa within 50 years was a viable idea.[86] The idea was ridiculed by many, but gained support from some natural history experts.[87]

In literature and culture[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Heinrich Harder portrayed moa being hunted by Māori in the classic German collecting cards about extinct and prehistoric animals, "Tiere der Urwelt", in the early 1900s.

Allen Curnow's poem, "The Skeleton of the Great Moa in the Canterbury Museum, Christchurch" was published in 1943.[88][89]

- ^ S. Brands, 2008

- ^ bulletin florida state museum - UFDC Image Array 2 - University of Florida

- ^ a b Stephenson, Brent (2009) Errore nelle note: Tag

<ref>non valido; il nome "Stephenson" è stato definito più volte con contenuti diversi - ^ In alcune lingue Polinesiane (Tahitiano, Maori delle Isole Cook, Samoano...), il termine "moa" vuol dire genericamente "pollame" (Dictionary of the Tahitian Academy {fr/ty} Archiviato il 5 aprile 2008 in Internet Archive.; Jasper Buse, Raututi Taringa, "Cook islands Maori Dictionary" (1995); Samoan lexicon Archiviato il 10 gennaio 2010 in Internet Archive.)

- ^ a b OSNZ, 2009

- ^ a b S. J. J. F. Davies (2003).

- ^ Little bush moa | New Zealand Birds Online, su nzbirdsonline.org.nz. URL consultato il 24 luglio 2020.

- ^ a b George L. W. Perry, Andrew B. Wheeler, Jamie R. Wood e Janet M. Wilmshurst, A high-precision chronology for the rapid extinction of New Zealand moa (Aves, Dinornithiformes), in Quaternary Science Reviews, vol. 105, 1º dicembre 2014, pp. 126-135, Bibcode:2014QSRv..105..126P, DOI:10.1016/j.quascirev.2014.09.025. URL consultato il 22 dicembre 2014.

- ^ A. David M. Latham, M. Cecilia Latham, Janet M. Wilmshurst, David M. Forsyth, Andrew M. Gormley, Roger P. Pech, George L. W. Perry e Jamie R. Wood, A refined model of body mass and population density in flightless birds reconciles extreme bimodal population estimates for extinct moa, in Ecography, vol. 43, n. 3, marzo 2020, pp. 353-364, DOI:10.1111/ecog.04917, ISSN 0906-7590.

- ^ a b Phillips et al. (2010).

- ^ Story: Moa, su govt.nz. URL consultato il 15 gennaio 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Worthy e Holdaway (2002).

- ^ Theo Schoon, Cave drawing of a moa, su Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand, Te Ara.

- ^ Te Manunui Rock Art Site, su Heritage New Zealand.

- ^ M. E. Allentoft e N. J. Rawlence, Moa's Ark or volant ghosts of Gondwana? Insights from nineteen years of ancient DNA research on the extinct moa (Aves: Dinornithiformes) of New Zealand (PDF), in Annals of Anatomy - Anatomischer Anzeiger, vol. 194, n. 1, 20 gennaio 2012, pp. 36-51, DOI:10.1016/j.aanat.2011.04.002, PMID 21596537.

- ^ a b K. J. Mitchell, B. Llamas, J. Soubrier, N. J. Rawlence, T. Worthy, J. Wood, M. S. Y. Lee e A. Cooper, Ancient DNA reveals elephant birds and kiwi are sister taxa and clarifies ratite bird evolution (PDF), in Science, vol. 344, n. 6186, 23 maggio 2014, pp. 898-900, Bibcode:2014Sci...344..898M, DOI:10.1126/science.1251981, PMID 24855267 (archiviato dall'url originale il 30 maggio 2019).

- ^ A. J. Baker, O. Haddrath, J. D. McPherson e A. Cloutier, Genomic Support for a Moa-Tinamou Clade and Adaptive Morphological Convergence in Flightless Ratites, in Molecular Biology and Evolution, vol. 31, n. 7, 2014, pp. 1686-1696, DOI:10.1093/molbev/msu153, PMID 24825849.

- ^ a b c Turvey et al. (2005).

- ^ a b c L. J. Huynen et al. (2003).

- ^ a b c d M. Bunce et al. (2003).

- ^ M. Bunce, Trevor Worthy, M. J. Phillips, R. Holdaway, E. Willerslev, J. Haile, B. Shapiro, R. P. Scofield, A. Drummond, P. J. J. Kamp e A. Cooper, The evolutionary history of the extinct ratite moa and New Zealand Neogene paleogeography, in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 106, n. 49, 2009, pp. 20646-20651, Bibcode:2009PNAS..10620646B, DOI:10.1073/pnas.0906660106, PMC 2791642, PMID 19923428.

- ^ B. J. Gill doi=10.3853/j.0067-1975.62.2010.1535, Regional comparisons of the thickness of moa eggshell fragments (Aves: Dinornithiformes). In Proceedings of the VII International Meeting of the Society of Avian Paleontology and Evolution, ed. W.E. Boles and Trevor Worthy (PDF), in Records of the Australian Museum, vol. 62, 2010, pp. 115-122 (archiviato dall'url originale l'11 aprile 2019).

- ^ T. Worthy e R. P. Scofield, Twenty-first century advances in knowledge of the biology of moa (Aves: Dinornithiformes): A new morphological analysis and moa diagnoses revised, in New Zealand Journal of Zoology, vol. 39, n. 2, 2012, pp. 87-153, DOI:10.1080/03014223.2012.665060.

- ^ A. J. Baker, L. J. Huynen, O. Haddrath, C. D. Millar e D. M. Lambert, Reconstructing the tempo and mode of evolution in an extinct clade of birds with ancient DNA: The giant moas of New Zealand, in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 102, n. 23, 2005, pp. 8257-8262, Bibcode:2005PNAS..102.8257B, DOI:10.1073/pnas.0409435102, PMC 1149408, PMID 15928096.

- ^ Worthy (1987).

- ^ Worthy et al. (1988).

- ^ a b c d A. J. D. Tennyson, T. Worthy, C. M. Jones, R. P. Scofield e S. J. Hand, Moa's Ark: Miocene fossils reveal the great antiquity of moa (Aves: Dinornithiformes) in Zealandia (PDF), in Records of the Australian Museum, vol. 62, 2010, pp. 105-114, DOI:10.3853/j.0067-1975.62.2010.1546 (archiviato dall'url originale l'11 aprile 2019).

- ^ M. Bunce, T. Worthy, M. J. Phillips, R. Holdaway, E. Willerslev, J. Hailef, B. Shapiro, R. P. Scofield, A. Drummond, P. J. J. Kampk e A. Cooper, The evolutionary history of the extinct ratite moa and New Zealand Neogene paleogeography, in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 106, n. 49, 2009, pp. 20646-20651, Bibcode:2009PNAS..10620646B, DOI:10.1073/pnas.0906660106, PMC 2791642, PMID 19923428.

- ^ Morten Allentoft e Nicolas Rawlence, Moa's ark or volant ghosts of Gondwana? Insights from nineteen years of ancient DNA research on the extinct moa (Aves: Dinornithiformes) of New Zealand (PDF), in Annals of Anatomy, vol. 194, n. 1, 2012, pp. 36-51, DOI:10.1016/j.aanat.2011.04.002, PMID 21596537.

- ^ Morten Allentoft e Nicolas Rawlence, Moa's ark or volant ghosts of Gondwana? Insights from nineteen years of ancient DNA research on the extinct moa (Aves: Dinornithiformes) of New Zealand, in Annals of Anatomy, vol. 194, n. 1, 2012, pp. 36-51, DOI:10.1016/j.aanat.2011.04.002, PMID 21596537.

- ^ T. Yuri, Parsimony and model-based analyses of indels in avian nuclear genes reveal congruent and incongruent phylogenetic signals, in Biology, vol. 2, n. 1, 2013, pp. 419-444, DOI:10.3390/biology2010419, PMC 4009869, PMID 24832669.

- ^ Worthy, Trevor (1998)a

- ^ Worthy, Trevor (1998)b

- ^ Worthy, Trevor & Holdaway, Richard (1993)

- ^ Worthy, Trevor & Holdaway, Richard (1994)

- ^ Worthy, Trevor & Holdaway, Richard (1995)

- ^ Worthy, Trevor & Holdaway, Richard (1996)

- ^ Buick L.T., The Moa-Hunters of New Zealand: Sportsman of the Stone Age – Chapter I. Did The Maori Know The Moa?, in Victoria University of Wellington Catalogue – New Zealand Texts Collection, W & T Avery Ltd., 1937.

- ^ Teviotdale D., The material culture of the Moa-hunters in Murihiku – 2. Evidence of Zoology, in The Journal of the Polynesian Society, vol. 41, n. 162, 1932, pp. 81–120.

- ^ Burrows, et al. (1981)

- ^ a b c Wood (2007)

- ^ Horrocks, et al. (2004)

- ^ a b George W. Gibbs, Ghosts of Gondwana: the history of life in New Zealand, Nelson, N.Z., Craig Potton Pub, 2006, ISBN 978-1877333484.

- ^ Moas as rockhounds, in Nature, vol. 281, n. 5727, 1979, pp. 103–104, DOI:10.1038/281103b0.

- ^ Extreme reversed sexual size dimorphism in the extinct New Zealand moa Dinornis (PDF), in Nature, vol. 425, n. 6954, 2003, pp. 172–175, DOI:10.1038/nature01871.

- ^ Hartree (1999)

- ^ a b Wood, J.R. (2008)

- ^ Gill, B.J. (2007)

- ^ a b Huynen, Leon; Gill, Brian J.; Millar, Craig D.; and Lambert, David M. (2010)

- ^ Yong, Ed. (2010)

- ^ (English) Mike Pole, A vanished ecosystem: Sophora microphylla (Kōwhai) dominated forest recorded in mid-late Holocene rock shelters in Central Otago, New Zealand, in Palaeontologia Electronica, vol. 25, n. 1, 31 December 2021, pp. 1–41, DOI:10.26879/1169. Lingua sconosciuta: English (aiuto)

- ^ Philippa Mein Smith, A Concise History of New Zealand, Cambridge University Press, 2012, pp. 2, 5–6, ISBN 978-1107402171.

- ^ Naïve birds and noble savages – a review of man-caused prehistoric extinctions of island birds, in Ecography, vol. 16, n. 3, 1993, pp. 229–250, DOI:10.1111/j.1600-0587.1993.tb00213.x.

- ^ Holdaway & Jacomb (2000)

- ^ a b c d Fuller, Errol (1987)

- ^ Alice McKenzie and the Moa, su radionz.co.nz.

- ^ Alice Mackenzie describes seeing a moa and talks about her book, Pioneers of Martins Bay, su ngataonga.org.nz.

- ^ a b c Anderson (1989)

- ^ Atholl Anderson, Prodigious Birds: Moas and Moa-Hunting in New Zealand, Cambridge University Press, 1990.

- ^ Purcell, Rosamond (1999)

- ^ Gould, C. (1886)

- ^ Heuvelmans, B (1959)

- ^ a b c Laing, Doug (2008)

- ^ The New Zealand Moa: From Extinct Bird to Cryptid, in Skeptical Briefs, vol. 27, n. 1, Center for Inquiry, 26 May 2017, pp. 8–9.

- ^ The New Zealand Moa: From Extinct Bird to Cryptid, in Skeptical Inquirer, 26 May 2017.

- ^ Polack, J.S. (1838)

- ^ Hill, H. (1913)

- ^ Dieffenbach, E. (1843)

- ^ (EN) New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage Te Manatu Taonga, 4. – Moa – Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand, su teara.govt.nz.

- ^ Berentson, Quinn., Moa : the life and death of New Zealand's legendary bird, Nelson, N.Z., Craig Potton, 2012, ISBN 978-1877517846.

- ^ Holdaway, Richard & Worthy, Trevor (1997)

- ^ Template:DNZB

- ^ Wood, J.R., et al. (2008)

- ^ Digitising moa, su aucklandmuseum.com. URL consultato il 2 February 2022.

- ^ a b Owen, R. (1879)

- ^ Hutton, F.W. & Coughtrey, M. (1875)

- ^ a b Buller, W.L. (1888)

- ^ Hamilton, A. (1894)

- ^ Vickers-Rich, et al. (1995)

- ^ Worthy, Trevor (1989)

- ^ Forrest, R.M. (1987)

- ^ DNA content and distribution in ancient feathers and potential to reconstruct the plumage of extinct avian taxa, in Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, vol. 276, n. 1672, 2009, pp. 3395–3402, DOI:10.1098/rspb.2009.0755.

- ^ Le Roux, M., "Scientists plan to resurrect a range of extinct animals using DNA and cloning", Courier Mail, 23 April 2013. Retrieved 25 July 2014.

- ^ Moa genes could rise from the dead, in New Scientist, vol. 153, n. 2063, 1997.

- ^ "Life in the Old Moa Yet", New Zealand Science Monthly, February 1997. Retrieved 25 July 2014.

- ^ O'Brien, T. Mallard: Bring the moa back to life within 50 years", 3news, 1 July 2014. Retrieved 25 July 2014.

- ^ Tohill, M.-J., "Expert supports Moa revival idea", stuff.co.nz, 9 July 2014. Retrieved 25 July 2014.

- ^ A poem a day: The Skeleton of the Great Moa in the Canterbury Museum, Christchurch – Allen Curnow, su nzpoems.blogspot.com, 25 April 2011.

- ^ Curnow, Allen (1944). Sailing or Drowning. Wellington: Progressive Publishing Society.

Errore nelle note: Sono presenti dei marcatori <ref> per un gruppo chiamato "N" ma non è stato trovato alcun marcatore <references group="N"/> corrispondente