Utente:Naomiemme/Sandbox

Storia del suffragio nei diversi continenti[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Africa[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Egitto[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

In Egitto il suffragio femminile venne supportato nel 1956 dall'allora Presidente Gamal Abdel-Nasser. Il voto era stato negato in precedenza nel periodo dell'occupazione britannica[1].

Sierra Leone[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Una delle prime occasioni durante le quali venne concesso alle donne di votare fu il Nova Scotian settlers a Freetown. Nelle elezioni del 1792, tutte le capofamiglia potevano votare e un terzo di queste erano di etnia africana.[2] Le donne conquistarono il diritto di voto in Sierra Leone nel 1930.[3]

Sud Africa[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

La franchigia fu estesa alle donne bianche dai 21 anni in su dal Women's Enfranchisement Act, 1930. Le prime elezioni generali nelle quali alle donne fu concesso di votare si svolsero nel 1933. In quell'occasione Leila Reitz (moglie di Deneys Reitz) fu la prima donna ad essere eletta Membro del Parlamento, rappresentando Parktown per il South African Party. Il diritto al voto degli uomini di colore era molto limitato a Cape Province e Natal (Transvaal e Orange Free State negavano del tutto il diritto di voto sia agli uomini di colore sia ai bianchi stranieri). Queste limitazioni non erano estese alle donne, e furono progressivamente eliminate fra il 1936 e il 1968.

Il diritto di voto per l'Assemblea legislativa del Transkei, istituito nel 1963 per il Transkei bantustan, fu concesso a tutti i cittadini adulti del Transkei, comprese le donne. Disposizioni analoghe sono state messe in atto per le assemblee legislative create per altri bantustan. Tutti i cittadini adulti di colore potevano votare per il Coloured Persons Representative Council, istituito nel 1968 con poteri legislativi limitati; il consiglio fu tuttavia abolito nel 1980. Allo stesso modo, tutti i cittadini indiani adulti avevano diritto a votare per il South African Indian Council nel 1981. Nel 1984 fu istituito il Parlamento Tricamerale e il diritto di voto per la Camera dei Rappresentanti e la Camera dei Delegati era concesso a tutti i cittadini adulti di colore e a tutti gli indiani, rispettivamente.

Nel 1994 i bantustan e il Parlamento Tricamerale furono aboliti e il diritto di voto per l'Assemblea nazionale fu concesso a tutti i cittadini adulti.

Rhodesia Meridionale[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Le donne bianche della Rhodesia meridionale ottennero il voto nel 1919 e Ethel Tawse Jollie (1875–1950) fu eletta nella legislatura della Rhodesia meridionale nel 1920-1928, la prima donna a sedere in un parlamento del Commonwealth nazionale fuori da Westminster. L'afflusso di donne coloni dalla Gran Bretagna si rivelò un fattore decisivo nel referendum del 1922 che ha respinto l'annessione di un Sudafrica sempre più sotto il dominio dei tradizionalisti nazionalisti Afrikaner a favore della "Rhodesian Home Rule" o "governo responsabile". I maschi di colore di Rhodesia si sono qualificati per il voto nel 1923 (basato solo su proprietà, beni, reddito e alfabetizzazione). Non è chiaro quando la prima donna di colore si è qualificata per il voto.

Asia[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

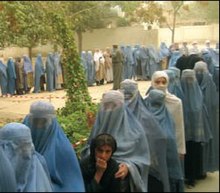

Afghanistan[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Le donne hanno avuto diritto di voto in Afghanistan dal 1965 (tranne durante il dominio talebano, 1996-2001, quando non si tenevano le elezioni).[4] Le donne sono state meno partecipi durante le votazioni in parte perché inconsapevoli del loro diritto di voto.[5] Nelle elezioni del 2014, il presidente eletto dell'Afghanistan si è impegnato a garantire alle donne pari diritti.[6]

Bangladesh[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Il Bangladesh è stato provincia del Bengala in India fino al 1947, per poi diventare parte del Pakistan. È diventata una nazione indipendente nel 1971. Le donne hanno ottenuto il suffragio nel 1947 e da allora hanno un posto riservato in parlamento. Il Bangladesh è degno di nota in quanto dal 1991 due donne, vale a dire lo sceicco Hasina e Begum Khaleda Zia, hanno continuato a ricoprire l'incarico di Primo Ministro del paese. Le donne hanno tradizionalmente svolto un ruolo minimo in politica al di là dell'anomalia dei due leader; poche concorrevano contro gli uomini alle elezioni e pertanto poche sono state elette ministri. Di recente, tuttavia, le donne sono diventate più attive in politica, con diversi importanti incarichi ministeriali assegnati a donne e la loro partecipazione alle elezioni nazionali, distrettuali e comunali contro gli uomini, riportando diverse vittorie. Choudhury e Hasanuzzaman sostengono che le forti tradizioni patriarcali del Bangladesh spiegano perché le donne sono così riluttanti a farsi avanti in politica.[7]

India[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Alle donne in India fu concesso di votare fin dalle prime elezioni generali dopo l'indipendenza dell'India nel 1947, eccetto durante il periodo del dominio britannico.[8] L'Associazione delle donne indiane (WIA) è stata fondata nel 1917. Ha lottato per far ottenere alle donne il diritto di ricoprire cariche legislative sulla stessa base degli uomini. Queste posizioni sono state approvate dal principale gruppo politico, l' Indian National Congress.[9] Le femministe britanniche e indiane si unirono nel 1918 per pubblicare una rivista chiamata Stri Dharma che presentava notizie internazionali da una prospettiva femminista.[10] Nel 1919, nelle riforme di Montagu – Chelmsford, gli inglesi istituirono legislature provinciali che avevano il potere di concedere il suffragio femminile. Madras nel 1921 concesse il diritto di voto alle donne ricche e istruite, alle stesse condizioni degli uomini. Seguirono le altre province, ma non gli stati principeschi (che non avevano neppure il voto per gli uomini, essendo monarchie).[9] Nella provincia del Bengala, l'assemblea provinciale lo respinse nel 1921, ma un'intensa campagna portò alla vittoria quello stesso anno. Il successo nel Bengala dipese dalle donne indiane della classe media, emerse da un'élite urbana in rapida crescita. Esse collegarono la loro crociata a un'agenda nazionalista moderata, mostrando come si potesse partecipare pienamente alla costruzione della nazione avendo il potere di voto. Nel farlo, evitarono accuratamente di attaccare i ruoli di genere tradizionali sostenendo che le tradizioni potrebbero coesistere con la modernizzazione politica.[11]

Mentre le donne facoltose e istruite di Madras hanno ottenuto il diritto di voto nel 1921, nel Punjab i Sikh hanno concesso alle donne pari diritti di voto nel 1925, indipendentemente dal loro titolo di studio o dal fatto di essere ricche o meno. Ciò accadde con l'approvazione della Legge Gurdwara. La bozza originale del Gurdwara Act inviata dagli inglesi al Comitato Sharomani Gurdwara Prabhandak (SGPC) non includeva le donne Sikh, ma i Sikh inserirono la clausola senza che le donne dovessero chiederla. L'uguaglianza delle donne con gli uomini è sancita dal Guru Granth Sahib, la sacra scrittura della fede Sikh.

Nel Government of India Act del 1935, il British Raj istituì un sistema di seggi separati per le donne, cosa alla quale la maggior parte delle leader si oppose. Nel 1931 il Congresso promise un'unione quando salì al potere e rispetto la sua promessa promulgando uguali diritti di voto per uomini e donne nel 1947.[12]

Indonesia[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

L'Indonesia concesse alle donne il diritto di voto per i consigli comunali nel 1905. Solo gli uomini che sapevano leggere e scrivere potevano votare, escludendo in questo modo molti uomini non europei. All'epoca, il tasso di alfabetizzazione per gli uomini era dell'11% e per le donne del 2%. Il gruppo principale che premette per il suffragio femminile in Indonesia fu il Dutch Vereeninging voor Vrouwenkiesrecht (VVV-Women's Suffrage Association), fondato nei Paesi Bassi nel 1894. VVV cercò di attirare membri indonesiani, ma ebbe un successo molto limitato perché i leader dell'organizzazione avevano poca abilità nel relazionarsi anche con la classe istruita. Nel 1918 fu formato il primo organo rappresentativo nazionale, il Volksraad, che escludeva ancora le donne dal voto. Nel 1935, l'amministrazione coloniale usò il suo potere di nomina per nominare una donna europea al Volksraad. Nel 1938, le donne ottennero il diritto di essere elette nelle istituzioni rappresentative urbane, il che portò alcune donne indonesiane ed europee ad entrare nei consigli comunali. Alla fine, solo le donne e i consigli comunali europei potevano votare, escludendo tutte le altre donne e i consigli locali. Nel settembre del 1941, il Volksraad estese il voto alle donne di tutte le etnie. Infine, nel novembre del 1941, il diritto di voto per i consigli comunali fu concesso a tutte le donne su una base analoga agli uomini (ovvero basato sui titoli di proprietà e titoli di studio).[13]

Iran[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Un referendum del gennaio 1963 approvato in modo schiacciante dagli elettori conferì alle donne il diritto di voto, un diritto precedentemente negato loro in virtù della Costituzione iraniana del 1906, capitolo 2, Articolo 3.[4]

Israele[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Le donne hanno avuto pieno suffragio sin dalla proclamazione dello Stato di Israele nel 1948.

La prima donna ad essere eletta Primo Ministro di Israele fu Golda Meir nel 1969.

Giappone[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Sebbene alle donne fosse permesso di votare in alcune prefetture già nel 1880, il suffragio femminile fu emanato a livello nazionale nel 1945.[14]

Corea

Le donne della Corea del Sud ottennero il diritto di voto nel 1948.[15]

Kuwait[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Quando il voto fu introdotto per la prima volta in Kuwait nel 1985, le donne vi potevano prendere parte.[16] Il diritto di voto fu poi temporaneamente rimosso, per essere ripristinato definitivamente nel Maggio del 2005 dal Parlamento Kuwaiti.[17]

Lebanon[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Pakistan[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Il Pakistan fece parte del British Raj fino al 1947, quando ottenne l'indipendenza. Le donne ricevettero il pieno suffragio nel 1947. Le donne leader musulmane di tutte le classi sostenevano attivamente il movimento pakistano nella metà degli anni '40, anche tramite l'organizzazione di manifestazioni pubbliche su larga scala. Il movimento era guidato da mogli e altri parenti di importanti politici. Nel novembre 1988, Benazir Bhutto divenne la prima donna musulmana ad essere eletta Primo Ministro di un paese musulmano.[18]

La prima Aurat March (Marcia delle donne) si è tenuta in Pakistan l'8 marzo 2018 (nella città di Karachi). Nel 2019 ne è stata organizzata una a Lahore e Karachi da un collettivo femminile chiamato Hum Auratein (We the Women), e in altre parti del paese, tra cui Islamabad, Hyderabad, Quetta, Mardan e Faislabad, dal fronte democratico femminile (WDF), Women Action Forum (WAF) e altri. [19] La marcia è stata approvata dalla Lady Health Workers Association e ha incluso rappresentanti di diverse organizzazioni per i diritti delle donne.[20][21] La marcia aveva come scopo richiedere una maggiore responsabilità riguardo la violenza contro le donne e il sostegno alle donne che subiscono violenze e molestie da parte delle forze di sicurezza, negli spazi pubblici, a casa e sul posto di lavoro.[22] I rapporti suggeriscono che sempre più donne si affrettarono ad unirsi alla marcia, fino a quando la folla fu dispersa. Le donne (così come gli uomini) portavano poster con frasi come "Le donne sono esseri umani, non onore", che divenne un grido di battaglia.

Filippine[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Le Filippine sono state uno dei primi paesi in Asia a garantire alle donne il diritto di voto.[23] Il suffragio nelle Filippine fu raggiunto a seguito di un plebiscito speciale per sole donne tenutosi il 30 aprile 1937, durante il quale 447.725 di esse - circa il novanta per cento - votarono a favore del suffragio femminile contro 44.307 che votarono contro. In conformità con la Costituzione del 1935, l'Assemblea nazionale approvò una legge che estendeva il diritto di suffragio alle donne, che rimane fino ai giorni nostri.[24][23]

Arabia Saudita[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Alla fine del settembre 2011, il re Abdullah bin Abdulaziz al-Saud dichiarò che le donne sarebbero state in grado di votare e candidarsi per la carica a partire dal 2015. Ciò valeva per i consigli municipali, che sono gli unici organi semi-eletti del regno, i quali hanno pochi poteri e la metà dei seggi è elettiva.[25] Le elezioni del consiglio si svolgevano già dal 2005,[26][27] ma è proprio dal dicembre 2015 che le donne saudite hanno avuto la possibilità di votare e concorrere per le cariche[28] e in quella stessa occasione Salma Biz Hizab al-Oteibi è diventata la prima donna eletta in Arabia Saudita, ottenendo un seggio nel consiglio di Madrakah nella provincia della Mecca.[29] In tutto furono venti le donne elette nei consigli municipali durante quelle elezioni.[30]

Il re dichiarò anche che le donne avrebbero potuto essere nominate nel Consiglio della Shura, un organo non eletto che emetteva pareri consultivi sulla politica nazionale.[31] "Questa è una grande notizia", disse al riguardo la scrittrice saudita e attivista per i diritti delle donne Wajeha al-Huwaider. "Le voci delle donne saranno finalmente ascoltate. Ora è il momento di rimuovere altre barriere come il divieto per le donne di guidare e non poter vivere una vita normale senza tutori maschi." Robert Lacey, autore di due libri sull'Arabia Saudita, ha detto "Questo è il primo discorso positivo e progressivo al di fuori del governo dalla primavera araba ... Prima gli avvertimenti, poi i pagamenti, ora gli inizi di una solida riforma". Il re fece l'annuncio in un discorso di cinque minuti al Consiglio Shura.[26] Nel gennaio 2013, il re Abdullah ha emesso due decreti reali, concedendo alle donne trenta seggi nel consiglio e affermando che le donne devono sempre tenere almeno un quinto dei seggi nel consiglio.[32] Secondo i decreti, le donne membri del consiglio devono essere "impegnate nelle discipline islamiche della Shariah senza alcuna violazione" ed essere "moderate dal velo religioso".[32] I decreti dicevano anche che i membri del consiglio femminile sarebbero entrati nell'edificio del consiglio da cancelli speciali, si sarebbero seduti in posti riservati alle donne e avrebbero pregato in luoghi di culto speciali.[32] In precedenza, i funzionari hanno affermato che uno schermo avrebbe separato i sessi e una rete di comunicazione interna avrebbe consentito a uomini e donne di comunicare.[32] Le donne hanno aderito per la prima volta al consiglio nel 2013, occupando trenta seggi,[33][34] due dei quali occupati da due donne reali saudite, Sara bint Faisal Al Saud e Moudi bint Khalid Al Saud.[35] Inoltre, nel 2013 tre donne sono state nominate vicepresidenti di tre commissioni: Thurayya Obeid è stata nominata vicepresidente della commissione per i diritti umani e le petizioni, Zainab Abu Talib, vicepresidente della commissione per l'informazione e la cultura, e Lubna Al Ansari vicepresidente della commissione per la salute e l'ambiente.[33]

Sri Lanka[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Nel 1931 lo Sri Lanka (a quel tempo Ceylon) divenne uno dei primi paesi asiatici a consentire il diritto di voto alle donne di età superiore ai 21 anni senza alcuna restrizione. Da allora, le donne hanno goduto di una presenza significativa nell'arena politica dello Sri Lanka. Il culmine di questa condizione favorevole per le donne sono state le elezioni generali del luglio 1960, in cui Ceylon ha eletto come Primo Ministro Sirimavo Bandaranaike, la prima donna a capo del governo eletta democraticamente al mondo. Anche sua figlia, Chandrika Kumaratunga, divenne Primo Ministro più tardi nel 1994, e lo stesso anno fu eletta Presidente Esecutivo dello Sri Lanka, rendendola la quarta donna al mondo ad essere eletta Presidente e la prima Presidente Esecutiva.

Europe[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

In Europe, the last countries to enact women's suffrage were Switzerland and Liechtenstein. In Switzerland, women gained the right to vote in federal elections in 1971;[36] but in the canton of Appenzell Innerrhoden women obtained the right to vote on local issues only in 1991, when the canton was forced to do so by the Federal Supreme Court of Switzerland.[37] In Liechtenstein, women were given the right to vote by the women's suffrage referendum of 1984. Three prior referendums held in 1968, 1971 and 1973 had failed to secure women's right to vote.[38]

Austria[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

It was only after the breakdown of the Habsburg Monarchy, that Austria would grant the general, equal, direct and secret right to vote to all citizens, regardless of sex, through the change of the electoral code in December 1918.[39] The first elections in which women participated were the February 1919 Constituent Assembly elections.[40]

Azerbaijan[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Universal voting rights were recognized in Azerbaijan in 1918 by the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic.[41]

Belgium[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

A revision of the constitution in October 1921 (it changed art. 47 of the Constitution of Belgium of 1831) introduced the general right to vote according to the "one man, one vote" principle. Art. 47 allowed widows of World War I to vote at the national level as well.[42] The introduction of women's suffrage was already put onto the agenda at the time, by means of including an article in the constitution that allowed approval of women's suffrage by special law (meaning it needed a 2/3 majority to pass).[43] This happened in March 1948. In Belgium, voting is compulsory.

Bulgaria[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Bulgaria was liberated from Ottoman rule in 1878. Although the first adopted constitution, the Tarnovo Constitution (1879), gave women equal election rights, in fact women were not allowed to vote and to be elected. The Bulgarian Women's Union was an umbrella organization of the 27 local women's organisations that had been established in Bulgaria since 1878. It was founded as a reply to the limitations of women's education and access to university studies in the 1890s, with the goal to further women's intellectual development and participation, arranged national congresses and used Zhenski glas as its organ. However, they have limited success, and women were allowed to vote and to be elected only after when Communist rule was established.

Croatia[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Czechia[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

In the former Bohemia, taxpaying women and women in "learned profession[s]" were allowed to vote by proxy and made eligible to the legislative body in 1864.[44] The first Czech female MP was elected to the Diet of Bohemia in 1912. The Declaration of Independence of the Czechoslovak Nation from 18 October 1918 declared that “our democracy shall rest on universal suffrage. Women shall be placed on equal footing with men, politically, socially, and culturally,” and women were appointed to the Revolutionary National Assembly (parliament) on 13 November 1918. On 15 June 1919, women voted in local elections for the first time. Women were guaranteed equal voting rights by the constitution of the Czechoslovak Republic in February 1920 and were able to vote for the parliament for the first time in April 1920.[45]

Denmark[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

In Denmark, the Danish Women's Society (DK) debated, and informally supported, women's suffrage from 1884, but it did not support it publicly until in 1887, when it supported the suggestion of the parliamentarian Fredrik Bajer to grant women municipal suffrage.[46] In 1886, in response to the perceived overcautious attitude of DK in the question of women suffrage, Matilde Bajer founded the Kvindelig Fremskridtsforening (or KF, 1886–1904) to deal exclusively with the right to suffrage, both in municipal and national elections, and it 1887, the Danish women publicly demanded the right for women's suffrage for the first time through the KF. However, as the KF was very much involved with worker's rights and pacifist activity, the question of women's suffrage was in fact not given full attention, which led to the establishment of the strictly women's suffrage movement Kvindevalgretsforeningen (1889–1897).[46] In 1890, the KF and the Kvindevalgretsforeningen united with five women's trade worker's unions to found the De samlede Kvindeforeninger, and through this form, an active women's suffrage campaign was arranged through agitation and demonstration. However, after having been met by compact resistance, the Danish suffrage movement almost discontinued with the dissolution of the De samlede Kvindeforeninger in 1893.[46]

In 1898, an umbrella organization, the Danske Kvindeforeningers Valgretsforbund or DKV was founded and became a part of the International Woman Suffrage Alliance (IWSA).[46] In 1907, the Landsforbundet for Kvinders Valgret (LKV) was founded by Elna Munch, Johanne Rambusch and Marie Hjelmer in reply to what they considered to be the much too careful attitude of the Danish Women's Society. The LKV originated from a local suffrage association in Copenhagen, and like its rival DKV, it successfully organized other such local associations nationally.[46]

Women won the right to vote in municipal elections on April 20, 1908. However it was not until June 5, 1915 that they were allowed to vote in Rigsdag elections.[47]

Estonia[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Estonia gained its independence in 1918 with the Estonian War of Independence. However, the first official elections were held in 1917. These were the elections of temporary council (i.e. Maapäev), which ruled Estonia from 1917–1919. Since then, women have had the right to vote.

The parliament elections were held in 1920. After the elections, two women got into the parliament – history teacher Emma Asson and journalist Alma Ostra-Oinas. Estonian parliament is called Riigikogu and during the First Republic of Estonia it used to have 100 seats.

Finland[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

The area that in 1809 became Finland was a group of integral provinces of the Kingdom of Sweden for over 600 years. Thus, women in Finland were allowed to vote during the Swedish Age of Liberty (1718–1772), during which conditional suffrage was granted to tax-paying female members of guilds.[48] However, this right was controversial. In Vaasa, there was opposition against women participating in the town hall discussing political issues, as this was not seen as their right place, and women's suffrage appears to have been opposed in practice in some parts of the realm: when Anna Elisabeth Baer and two other women petitioned to vote in Turku in 1771, they were not allowed to do so by town officials.[49]

The predecessor state of modern Finland, the Grand Duchy of Finland, was part of the Russian Empire from 1809 to 1917 and enjoyed a high degree of autonomy. In 1863, taxpaying women were granted municipal suffrage in the country side, and in 1872, the same reform was given to the cities.[44] In 1906, it became the first country in the world to implement full universal suffrage, as women could also stand as candidates. It also elected the world's first female members of parliament the following year.[50][51]

France[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

The 21 April 1944 ordinance of the French Committee of National Liberation, confirmed in October 1944 by the French provisional government, extended the suffrage to French women.[52][53] The first elections with female participation were the municipal elections of 29 April 1945 and the parliamentary elections of 21 October 1945. "Indigenous Muslim" women in French Algeria also known as Colonial Algeria, had to wait until a 3 July 1958 decree.[54][55]

Georgia[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Upon its declaration of independence on 26 May 1918, in the aftermath of the Russian Revolution, the Democratic Republic of Georgia extended suffrage to its female citizens. The women of Georgia first exercised their right to vote in the 1919 legislative election.[56]

Germany[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Women were granted the right to vote and be elected from the 12th November 1918.[4]

Greece[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Greece had had universal suffrage since its independence in 1832, but it excluded women. The first proposal to give Greek women the right to vote was made on 19 May 1922 by a member of parliament, supported by then Prime Minister Dimitrios Gounaris, during a constitutional convention.[57] The proposal garnered a narrow majority of those present when it was first proposed, but failed to get the broad 80% support needed to add it to the constitution.[57] In 1925 consultations began again, and a law was passed allowing women the right to vote in local elections, provided they were 30 years of age and had attended at least primary education.[57] The law remained unenforced, until feminist movements within the civil service lobbied the government to enforce it in December 1927 and March 1929.[57] Women were allowed to vote on a local level for the first time in the Thessaloniki local elections, on 14 December 1930, where 240 women exercised their right to do so.[57] Women's turnout remained low, at only around 15,000 in the national local elections of 1934, despite women being a narrow majority of the population of 6.8 million.[57] Women could not stand for election, despite a proposal made by Interior minister Ioannis Rallis, which was contested in the courts; the courts ruled that the law only gave women "a limited franchise" and struck down any lists where women were listed as candidates for local councils.[57] Misogyny was rampant in that era; Emmanuel Rhoides is quoted as having said that "two professions are fit for women: housewife and prostitute".[58]

On a national level women over 18 voted for the first time in April 1944 for the National Council, a legislative body set up by the National Liberation Front resistance movement. Ultimately, women won the legal right to vote and run for office on 28 May 1952. Eleni Skoura, again from Thessaloniki, became the first woman elected to the Hellenic Parliament in 1953, with the conservative Greek Rally, when she won a by-election against another female opponent.[59] Women were finally able to participate in the 1956 election, with two more women becoming Members of Parliament; Lina Tsaldari, wife of former Prime Minister Panagis Tsaldaris, won the most votes of any candidate in the country and became the first female minister in Greece under the conservative National Radical Union government of Konstantinos Karamanlis.[59]

No woman has been elected Prime Minister of Greece, but Vassiliki Thanou-Christophilou served as the country's first female Prime Minister, heading a caretaker government, between 27 August and 21 September 2015. The first woman to lead a major political party was Aleka Papariga, who served as General Secretary of the Communist Party of Greece from 1991 to 2013.

Hungary[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

In Hungary, although it was already planned in 1818, the first occasion when women could vote was the elections held in January 1920.

Isle of Man[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

In 1881, The Isle of Man (in the British Isles but not part of the United Kingdom) passed a law giving the vote to single and widowed women who passed a property qualification. This was to vote in elections for the House of Keys, in the Island's parliament, Tynwald. This was extended to universal suffrage for men and women in 1919.[60]

Italy[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

In Italy, women's suffrage was not introduced following World War I, but upheld by Socialist and Fascist activists and partly introduced by Benito Mussolini's government in 1925.[61] In April 1945, the provisional government decreed the enfranchisement of women allowing for the immediate appointment of women to public office, of which the first was Elena Fischli Dreher.[62] In the 1946 election, all Italians simultaneously voted for the Constituent Assembly and for a referendum about keeping Italy a monarchy or creating a republic instead. Elections were not held in the Julian March and South Tyrol because they were under Allied occupation.

The new version of article 51 Constitution recognizes equal opportunities in electoral lists.[63]

Liechtenstein[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

In Liechtenstein, women's suffrage was granted via referendum in 1984.[64]

Luxemburg[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

In Luxemburg, Marguerite Thomas-Clement spoke in favour of women suffrage in public debate through articles in the press in 1917-19; however, there was never any organized women suffrage movement in Luxemburg, as women suffrage was included without debate in the new democratic constitution of 1919.[65]

Netherlands[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Women were granted the right to vote in the Netherlands on August 9, 1919.[4] In 1917, a constitutional reform already allowed women to be electable. However, even though women's right to vote was approved in 1919, this only took effect from January 1, 1920.

The women's suffrage movement in the Netherlands was led by three women: Aletta Jacobs, Wilhelmina Drucker and Annette Versluys-Poelman. In 1889, Wilhelmina Drucker founded a women's movement called Vrije Vrouwen Vereeniging (Free Women’s Union) and it was from this movement that the campaign for women's suffrage in the Netherlands emerged. This movement got a lot of support from other countries, especially from the women's suffrage movement in England. In 1906 the movement wrote an open letter to the Queen pleading for women's suffrage. When this letter was rejected, in spite of popular support, the movement organised several demonstrations and protests in favor of women's suffrage. This movement was of great significance for women's suffrage in the Netherlands.[66]

Norway[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Liberal politician Gina Krog was the leading campaigner for women's suffrage in Norway from the 1880s. She founded the Norwegian Association for Women's Rights and the National Association for Women's Suffrage to promote this cause. Members of these organisations were politically well-connected and well organised and in a few years gradually succeeded in obtaining equal rights for women. Middle class women won the right to vote in municipal elections in 1901 and parliamentary elections in 1907. Universal suffrage for women in municipal elections was introduced in 1910, and in 1913 a motion on universal suffrage for women was adopted unanimously by the Norwegian parliament (Stortinget).[67] Norway thus became the first independent country to introduce women's suffrage.[68]

Poland[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Regaining independence in 1918 following the 123-year period of partition and foreign rule,[69] Poland immediately granted women the right to vote and be elected as of 28 November 1918.[4]

The first women elected to the Sejm in 1919 were: Gabriela Balicka, Jadwiga Dziubińska, Irena Kosmowska, Maria Moczydłowska, Zofia Moraczewska, Anna Piasecka, Zofia Sokolnicka, and Franciszka Wilczkowiakowa.[70][71]

Portugal[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Carolina Beatriz Ângelo was the first Portuguese woman to vote, in the Constituent National Assembly election of 1911,[72] taking advantage of a loophole in the country's electoral law.

In 1931 during the Estado Novo regime, women were allowed to vote for the first time, but only if they had a high school or university degree, while men had only to be able to read and write. In 1946 a new electoral law enlarged the possibility of female vote, but still with some differences regarding men. A law from 1968 claimed to establish "equality of political rights for men and women", but a few electoral rights were reserved for men. After the Carnation Revolution, women were granted full and equal electoral rights in 1976.[73][74]

Romania[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

The timeline of granting women's suffrage in Romania was gradual and complex, due to the turbulent historical period when it happened. The concept of universal suffrage for all men was introduced in 1918,[75] and reinforced by the 1923 Constitution of Romania. Although this constitution opened the way for the possibility of women's suffrage too (Article 6),[76] this did not materialize: the Electoral Law of 1926 did not grant women the right to vote, maintaining all male suffrage.[77] Starting in 1929, women who met certain qualifications were allowed to vote in local elections.[77] After the Constitution from 1938 (elaborated under Carol II of Romania who sought to implement an authoritarian regime) the voting rights were extended to women for national elections by the Electoral Law 1939,[78] but both women and men had restrictions, and in practice these restrictions affected women more than men (the new restrictions on men also meant that men lost their previous universal suffrage). Although women could vote, they could be elected only to the Senate and not to the Chamber of Deputies (Article 4 (c)).[78] (the Senate was later abolished in 1940). Due to the historical context of the time, which included the dictatorship of Ion Antonescu, there were no elections in Romania between 1940–1946. In 1946, Law no. 560 gave full equal rights to men and women to vote and to be elected in the Chamber of Deputies; and women voted in the 1946 Romanian general election.[79] The Constitution of 1948 gave women and men equal civil and political rights (Article 18).[80] Until the collapse of communism in 1989, all the candidates were chosen by the Romanian Communist Party, and civil rights were merely symbolic under this authoritarian regime.[81]

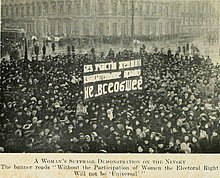

Russia[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Despite initial apprehension against enfranchising women for the right to vote for the upcoming Constituent Assembly election, the League for Women's Equality and other suffragists rallied throughout the year of 1917 for the right to vote. After much pressure (including a 40,000-strong march on the Tauride Palace), on July 20, 1917 the Provisional Government enfranchised women with the right to vote.[82]

San Marino[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

San Marino introduced women's suffrage in 1959,[73] following the 1957 constitutional crisis known as Fatti di Rovereta. It was however only in 1973 that women obtained the right to stand for election.[73]

Spain[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

During the Miguel Primo de Rivera[83] regime (1923–1930) only women who were considered heads of household were allowed to vote in local elections, but there were none at that time. Women's suffrage was officially adopted in 1931 despite the opposition of Margarita Nelken and Victoria Kent, two female MPs (both members of the Republican Radical-Socialist Party), who argued that women in Spain at that moment lacked social and political education enough to vote responsibly because they would be unduly influenced by Catholic priests. During the Franco regime in the "organic democracy" type of elections called "referendums" (Franco's regime was dictatorial) women over 21 were allowed to vote without distinction.[84] From 1976, during the Spanish transition to democracy women fully exercised the right to vote and be elected to office.

Sweden[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

During the Age of Liberty (1718–1772), Sweden had conditional women's suffrage.[85] Until the reform of 1865, the local elections consisted of mayoral elections in the cities, and elections of parish vicars in the countryside parishes. The Sockenstämma was the local parish council who handled local affairs, in which the parish vicar presided and the local peasantry assembled and voted, an informally regulated process in which women are reported to have participated already in the 17th century.[86] The national elections consisted of the election of the representations to the Riksdag of the Estates.

Suffrage was gender neutral and therefore applied to women as well as men if they filled the qualifications of a voting citizen.[85] These qualifications were changed during the course of the 18th-century, as well as the local interpretation of the credentials, affecting the number of qualified voters: the qualifications also differed between cities and countryside, as well as local or national elections.[85]

Initially, the right to vote in local city elections (mayoral elections) was granted to every burgher, which was defined as a taxpaying citizen with a guild membership.[85] Women as well as men were members of guilds, which resulted in women's suffrage for a limited number of women.[85] In 1734, suffrage in both national and local elections, in cities as well as countryside, was granted to every property owning taxpaying citizen of legal majority.[85] This extended suffrage to all taxpaying property owning women whether guild members or not, but excluded married women and the majority of unmarried women, as married women were defined as legal minors, and unmarried women were minors unless they applied for legal majority by royal dispensation, while widowed and divorced women were of legal majority.[85] The 1734 reform increased the participation of women in elections from 55 to 71 percent.[85]

Between 1726 and 1742, women voted in 17 of 31 examined mayoral elections.[85] Reportedly, some women voters in mayoral elections preferred to appoint a male to vote for them by proxy in the city hall because they found it embarrassing to do so in person, which was cited as a reason to abolish women's suffrage by its opponents.[85] The custom to appoint to vote by proxy was however used also by males, and it was in fact common for men, who were absent or ill during elections, to appoint their wives to vote for them.[85] In Vaasa in Finland (then a Swedish province), there was opposition against women participating in the town hall discussing political issues as this was not seen as their right place, and women's suffrage appears to have been opposed in practice in some parts of the realm: when Anna Elisabeth Baer and two other women petitioned to vote in Åbo in 1771, they were not allowed to do so by town officials.[49]

In 1758, women were excluded from mayoral elections by a new regulation by which they could no longer be defined as burghers, but women's suffrage was kept in the national elections as well as the countryside parish elections.[85] Women participated in all of the eleven national elections held up until 1757.[85] In 1772, women's suffrage in national elections was abolished by demand from the burgher estate. Women's suffrage was first abolished for taxpaying unmarried women of legal majority, and then for widows.[85] However, the local interpretation of the prohibition of women's suffrage varied, and some cities continued to allow women to vote: in Kalmar, Växjö, Västervik, Simrishamn, Ystad, Åmål, Karlstad, Bergslagen, Dalarna and Norrland, women were allowed to continue to vote despite the 1772 ban, while in Lund, Uppsala, Skara, Åbo, Gothenburg and Marstrand, women were strictly barred from the vote after 1772.[85]

While women's suffrage was banned in the mayoral elections in 1758 and in the national elections in 1772, no such bar was ever introduced in the local elections in the countryside, where women therefore continued to vote in the local parish elections of vicars.[85] In a series of reforms in 1813–1817, unmarried women of legal majority, "Unmarried maiden, who has been declared of legal majority", were given the right to vote in the sockestämma (local parish council, the predecessor of the communal and city councils), and the kyrkoråd (local church councils).[87]

In 1823, a suggestion was raised by the mayor of Strängnäs to reintroduce women's suffrage for taxpaying women of legal majority (unmarried, divorced and widowed women) in the mayoral elections, and this right was reintroduced in 1858.[86]

In 1862, tax-paying women of legal majority (unmarried, divorced and widowed women) were again allowed to vote in municipal elections, making Sweden the first country in the world to grant women the right to vote.[44] This was after the introduction of a new political system, where a new local authority was introduced: the communal municipal council. The right to vote in municipal elections applied only to people of legal majority, which excluded married women, as they were juridically under the guardianship of their husbands. In 1884 the suggestion to grant women the right to vote in national elections was initially voted down in Parliament.[88] During the 1880s, the Married Woman's Property Rights Association had a campaign to encourage the female voters, qualified to vote in accordance with the 1862 law, to use their vote and increase the participation of women voters in the elections, but there was yet no public demand for women's suffrage among women. In 1888, the temperance activist Emilie Rathou became the first woman in Sweden to demand the right for women's suffrage in a public speech.[89] In 1899, a delegation from the Fredrika Bremer Association presented a suggestion of women's suffrage to prime minister Erik Gustaf Boström. The delegation was headed by Agda Montelius, accompanied by Gertrud Adelborg, who had written the demand. This was the first time the Swedish women's movement themselves had officially presented a demand for suffrage.

In 1902 the Swedish Society for Woman Suffrage was founded. In 1906 the suggestion of women's suffrage was voted down in parliament again.[90] In 1909, the right to vote in municipal elections were extended to also include married women.[91] The same year, women were granted eligibility for election to municipal councils,[91] and in the following 1910–11 municipal elections, forty women were elected to different municipal councils,[90] Gertrud Månsson being the first. In 1914 Emilia Broomé became the first woman in the legislative assembly.[92]

The right to vote in national elections was not returned to women until 1919, and was practised again in the election of 1921, for the first time in 150 years.[48]

After the 1921 election, the first women were elected to Swedish Parliament after women's suffrage were Kerstin Hesselgren in the Upper chamber and Nelly Thüring (Social Democrat), Agda Östlund (Social Democrat) Elisabeth Tamm (liberal) and Bertha Wellin (Conservative) in the Lower chamber. Karin Kock-Lindberg became the first female government minister, and in 1958, Ulla Lindström became the first acting Prime Minister.[93]

Switzerland[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

A referendum on women's suffrage was held on 1 February 1959. The majority of Switzerland's men (67%) voted against it, but in some French-speaking cantons women obtained the vote.[94] The first Swiss woman to hold political office, Trudy Späth-Schweizer, was elected to the municipal government of Riehen in 1958.[95]

Switzerland was the last Western republic to grant women's suffrage; they gained the right to vote in federal elections in 1971 after a second referendum that year.[94] In 1991 following a decision by the Federal Supreme Court of Switzerland, Appenzell Innerrhoden became the last Swiss canton to grant women the vote on local issues.[96]

The first female member of the seven-member Swiss Federal Council, Elisabeth Kopp, served from 1984 to 1989. Ruth Dreifuss, the second female member, served from 1993 to 1999, and was the first female President of the Swiss Confederation for the year 1999. From 22 September 2010 until 31 December 2011 the highest political executive of the Swiss Confederation had a majority of female councillors (4 of 7); for the three years 2010, 2011, and 2012 Switzerland was presided by female presidency for three years in a row; the latest one was for the year 2017.[97]

Turkey[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

In Turkey, Atatürk, the founding president of the republic, led a secularist cultural and legal transformation supporting women's rights including voting and being elected. Women won the right to vote in municipal elections on March 20, 1930. Women's suffrage was achieved for parliamentary elections on December 5, 1934, through a constitutional amendment. Turkish women, who participated in parliamentary elections for the first time on February 8, 1935, obtained 18 seats.

In the early republic, when Atatürk ran a one-party state, his party picked all candidates. A small percentage of seats were set aside for women, so naturally those female candidates won. When multi-party elections began in the 1940s, the share of women in the legislature fell, and the 4% share of parliamentary seats gained in 1935 was not reached again until 1999. In the parliament of 2011, women hold about 9% of the seats. Nevertheless, Turkish women gained the right to vote a decade or more before women in such Western European countries as France, Italy, and Belgium – a mark of Atatürk's far-reaching social changes. [98]

United Kingdom[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

The campaign for women's suffrage in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland gained momentum throughout the early part of the 19th century, as women became increasingly politically active, particularly during the campaigns to reform suffrage in the United Kingdom. John Stuart Mill, elected to Parliament in 1865 and an open advocate of female suffrage (about to publish The Subjection of Women), campaigned for an amendment to the Reform Act 1832 to include female suffrage.[99] Roundly defeated in an all-male parliament under a Conservative government, the issue of women's suffrage came to the fore.

Until the 1832 Reform Act specified "male persons", a few women had been able to vote in parliamentary elections through property ownership, although this was rare.[100] In local government elections, women lost the right to vote under the Municipal Corporations Act 1835. Single women ratepayers received the right to vote in the Municipal Franchise Act 1869. This right was confirmed in the Local Government Act 1894 and extended to include some married women.[101][102][103][104] By 1900, more than 1 million single women were registered to vote in local government elections in England.[101]

In 1881, the Isle of Man (in the British Isles but not part of the United Kingdom) passed a law giving the vote to single and widowed women who passed a property qualification. This was to vote in elections for the House of Keys, in the Island's parliament, Tynwald. This was extended to universal suffrage for men and women in 1919.[105]

During the later half of the 19th century, a number of campaign groups for women's suffrage in national elections were formed in an attempt to lobby Members of Parliament and gain support. In 1897, seventeen of these groups came together to form the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), who held public meetings, wrote letters to politicians and published various texts.[106] In 1907 the NUWSS organized its first large procession.[106] This march became known as the Mud March as over 3,000 women trudged through the streets of London from Hyde Park to Exeter Hall to advocate women's suffrage.[107]

In 1903 a number of members of the NUWSS broke away and, led by Emmeline Pankhurst, formed the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU).[108] As the national media lost interest in the suffrage campaign, the WSPU decided it would use other methods to create publicity. This began in 1905 at a meeting in Manchester's Free Trade Hall where Edward Grey, 1st Viscount Grey of Fallodon, a member of the newly elected Liberal government, was speaking.[109] As he was talking, Christabel Pankhurst and Annie Kenney of the WSPU constantly shouted out, "Will the Liberal Government give votes to women?"[109] When they refused to cease calling out, police were called to evict them and the two suffragettes (as members of the WSPU became known after this incident) were involved in a struggle which ended with them being arrested and charged for assault.[110] When they refused to pay their fine, they were sent to prison for one week, and three days.[109] The British public were shocked and took notice at this use of violence to win the vote for women.

After this media success, the WSPU's tactics became increasingly violent. This included an attempt in 1908 to storm the House of Commons, the arson of David Lloyd George's country home (despite his support for women's suffrage). In 1909 Lady Constance Lytton was imprisoned, but immediately released when her identity was discovered, so in 1910 she disguised herself as a working class seamstress called Jane Warton and endured inhumane treatment which included force-feeding. In 1913, suffragette Emily Davison protested by interfering with a horse owned by King George V during the running of The Derby; she was trampled and died four days later. The WSPU ceased their militant activities during World War I and agreed to assist with the war effort.[111]

The National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies, which had always employed "constitutional" methods, continued to lobby during the war years, and compromises were worked out between the NUWSS and the coalition government.[112] The Speaker's Conference on electoral reform (1917) represented all the parties in both houses, and came to the conclusion that women's suffrage was essential. Regarding fears that women would suddenly move from zero to a majority of the electorate due to the heavy loss of men during the war, the Conference recommended that the age restriction be 21 for men, and 30 for women.[113][114][115]

On 6 February 1918, the Representation of the People Act 1918 was passed, enfranchising women over the age of 30 who met minimum property qualifications. About 8.4 million women gained the vote in Great Britain and Ireland.[116] In November 1918, the Parliament (Qualification of Women) Act 1918 was passed, allowing women to be elected into Parliament. The Representation of the People (Equal Franchise) Act 1928 extended the franchise in Great Britain and Northern Ireland to all women over the age of 21, granting women the vote on the same terms as men.[117]

In 1999, Time magazine, in naming Emmeline Pankhurst as one of the 100 Most Important People of the 20th Century, states: "...she shaped an idea of women for our time; she shook society into a new pattern from which there could be no going back".[118]

Oceania[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Australia[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Le discendenti femminili degli ammutinati del Bounty che vivevano su Pitcairn Islands ottennero diritto di voto nel 1838, e questo diritto è stato trasferito con il loro reinsediamento a Norfolk Island (ora un territorio estero australiano) nel 1856.[120]

Le donne proprietarie della colonia dell'Australia meridionale ottennero il voto alle elezioni locali (ma non alle elezioni parlamentari) nel 1861. Henrietta Dugdale costituì la prima società australiana di suffragio femminile a Melbourne, Victoria nel 1884. Le donne divennero idonee a votare per il Parlamento del Sud Australia nel 1895, così come gli uomini e le donne aborigeni.[119] Nel 1897, Catherine Helen Spence divenne la prima figura femminile a ricoprire incarichi politici, candidandosi senza successo alle elezioni come delegata alla Convenzione federale sulla Federazione australiana. L'Australia Occidentale garantì diritto di voto alle donne nel 1899.[121]

Le prime elezioni per il Parlamento del neo formato Commonwealth of Australia nel 1901 si basava sulle disposizioni elettorali delle sei colonie preesistenti, in modo che le donne che avevano il voto e il diritto di candidarsi al parlamento a livello statale avessero gli stessi diritti per le elezioni federali australiane del 1901. Nel 1902 il Parlamento del Commonwealth approvò il Commonwealth Franchise Act, che consentiva a tutte le donne di votare e candidarsi alle elezioni del Parlamento federale. L'anno seguente Nellie Martel, Mary Moore-Bentley, Vida Goldstein e Selina Siggins si presentarono alle elezioni.[121] La legge escludeva espressamente i "nativi" dai diritti, a meno che non fossero appartenenti ad uno degli stati facenti parte del Commonwealth. Nel 1949, il diritto di voto alle elezioni federali fu esteso a tutti gli indigeni che avevano prestato servizio nelle forze armate o che erano stati arruolati (Queensland, Australia occidentale e Territorio del Nord esclusero tuttavia le donne indigene dai diritti di voto). Le restanti restrizioni furono abolite nel 1962 dal Commonwealth Electoral Act.[122]

Nell'Assemblea legislativa dell'Australia occidentale del 1921 fu eletta Edith Cowan, prima donna in un Parlamento australiano. Nel 1943 Dame Enid Lyons, nella Camera dei rappresentanti, e la senatrice australiana Dorothy Tangney, furono le prime donne al Parlamento federale. Lyons divenne anche la prima donna a ricoprire un posto di governo nel ministero di Robert Menzies del 1949. Rosemary Follett è stata eletta Primo Ministro del Territorio della Capitale Australiana nel 1989, diventando la prima donna eletta a guidare uno stato o un territorio. Nel 2010, la popolazione della più antica città australiana, Sydney, aveva leader femminili che occupavano tutti i principali uffici politici, con Clover Moore come Lord Mayor, Kristina Keneally come Premier del Nuovo Galles del Sud, Marie Bashir come Governatore del New South Wales, Julia Gillard come Primo Ministro, Quentin Bryce come governatore generale dell'Australia ed Elisabetta II come regina dell'Australia.

Cook Islands[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Le donne in Rarotonga ottennero il diritto di voto nel 1893, poco dopo la Nuova Zelanda.[123]

Nuova Zelanda[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

La legge elettorale della Nuova Zelanda del 19 settembre 1893 fece di questo paese il primo al mondo a garantire alle donne il diritto di voto alle elezioni parlamentari.[120]

Il disegno di legge ha concesso il voto alle donne di tutte le razze. Alle donne neozelandesi fu negato il diritto di candidarsi al parlamento, tuttavia, fino al 1920. Nel 2005 quasi un terzo dei deputati eletti erano donne. Di recente le donne hanno anche occupato uffici importanti e simbolici come quelli del Primo Ministro (Jenny Shipley, Helen Clark e Jacinda Ardern), Governatore-Generale (Catherine Tizard e Silvia Cartwright), Capo della Giustizia (Sian Elias), Presidente della Camera dei Rappresentanti (Margaret Wilson), e dal 3 marzo 2005 al 23 agosto 2006, tutti e quattro questi incarichi erano ricoperti da donne, insieme alla regina Elisabetta come capo di stato.

America[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Le donne dell'America centrale e meridionale e quelle del Messico hanno ottenuto il diritto di voto più tardi rispetto a quanto avvenuto in Canada e negli Stati Uniti. Dall'Ecuador al Paraguay, per data di pieno suffragio: [124]

- 1929: Ecuador

- 1932: Uruguay

- 1934: Brazil, Cuba

- 1939: El Salvador

- 1941: Panama

- 1946: Guatemala, Venezuela

- 1947: Argentina

- 1948: Suriname

- 1949: Chile, Costa Rica

- 1952: Bolivia

- 1953: Mexico

- 1954: Belize, Colombia

- 1955: Honduras, Nicaragua, Peru,

- 1961: Paraguay[125]

Ci sono stati dibattiti politici, religiosi e culturali attorno al tema del suffragio femminile in questi paesi. Importanti sostenitori del suffragio femminile includono Hermila Galindo (Messico), Eva Perón (Argentina), Alicia Moreau de Justo (Argentina), Julieta Lanteri (Argentina), Celina Guimarães Viana (Brasile), Ivone Guimarães (Brasile), Henrietta Müller (Cile) , Marta Vergara (Cile), Lucila Rubio de Laverde (Colombia), María Currea Manrique (Colombia), Josefa Toledo de Aguerri (Nicaragua), Elida Campodónico (Panama), Clara González (Panama), Gumercinda Páez (Panama), Paulina Luisi Janicki (Uruguay), Carmen Clemente Travieso, (Venezuela).

Canada[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Lo status politico delle donne senza voto fu promosso dal Consiglio Nazionale delle Donne del Canada dal 1894 al 1918. Promosse una visione di "cittadinanza trascendente" per le donne. La votazione non era necessaria, poiché la cittadinanza doveva essere esercitata attraverso l'influenza personale e la sofferenza morale, attraverso l'elezione di uomini con un forte carattere morale e attraverso la crescita di figli di spirito pubblico. La posizione del Consiglio nazionale è stata integrata nella costruzione nazionale che ha cercato di sostenere il Canada come nazione di coloni bianchi. Mentre il movimento di suffragio femminile era importante per estendere i diritti politici delle donne bianche, era anche autorizzato attraverso argomentazioni basate sulla razza che collegavano le donne bianche alla necessità di proteggere la nazione dalla "degenerazione razziale".[126]

Le donne avevano diritto di voto in alcune province, come nell'Ontario dal 1850, dove le donne che possedevano delle proprietà potevano votare per gli amministratori della scuola.[127] Nel 1900 altre province avevano adottato disposizioni simili e nel 1916 Manitoba prese il comando estendendo il suffragio femminile. Allo stesso tempo i suffragisti hanno dato un forte sostegno al movimento di proibizione, specialmente in Ontario e nelle province occidentali.[128][129]

Il Wartime Elections Act del 1917 diede il voto alle donne britanniche che erano vedove di guerra o che avevano figli, mariti, padri o fratelli che prestavano servizio all'estero. Il primo ministro sindacalista Sir Robert Borden si è impegnato durante la campagna del 1917 a uguagliare il suffragio per le donne. Dopo la sua schiacciante vittoria, nel 1918 presentò una proposta di legge per estendere il voto alle donne. Il 24 maggio 1918, le donne considerate cittadine (non donne aborigene o la maggior parte delle donne di colore) divennero idonee al voto a patto che avessero "21 anni o più, non nate all'estero e soddisfacenti i requisiti di proprietà nelle province in cui vivono".[130]

La maggior parte delle donne del Quebec ottenne il pieno suffragio nel 1940.[130] Alle donne aborigene in tutto il Canada non fu concesso il diritto di voto federale fino al 1960.[131]

La prima donna eletta in parlamento fu Agnes Macphail in Ontario nel 1921.[132]

United States[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Prima che il diciannovesimo emendamento fosse approvato nel 1920, alcuni singoli stati degli Stati Uniti hanno concesso il suffragio femminile in alcuni tipi di elezioni. Alcuni hanno permesso alle donne di votare alle elezioni scolastiche, alle elezioni comunali e per i membri del Collegio elettorale. Altri territori, come Washington, Utah e Wyoming, hanno dato alle donne diritto di voto ancor prima di diventare stati.[133]

La costituzione del New Jersey del 1776 permise il voto a tutti i cittadini adulti che possedevano un certo numero di proprietà. Le leggi emanate nel 1790 e nel 1797 si riferivano agli elettori testualmente con "lui o lei" e le donne votavano regolarmente. Una legge approvata nel 1807, tuttavia, escludeva le donne dal voto in quello stato.[134]

Lydia Taft fu una delle prime donne in America coloniale a cui fu permesso di votare in tre riunioni della città del New England, a partire dal 1756, a Uxbridge, nel Massachusetts.[135] Il movimento del suffragio femminile era strettamente legato all'abolizionismo, con molti attivisti alla loro prima esperienza contro la schiavitù.[136]

Nel giugno 1848, Gerrit Smith fece del suffragio femminile uno dei punti cruciali del Partito Liberty. A luglio dello stesso anno, alla Convention delle Seneca Falls nello stato di New York, attivisti tra cui Elizabeth Cady Stanton e Susan B. Anthony hanno iniziato una lotta durata settant'anni da parte delle donne per assicurarsi il diritto di voto. I partecipanti hanno firmato un documento noto come Dichiarazione dei diritti e dei sentimenti, di cui Stanton era l'autore principale. La parità dei diritti è diventata il grido di battaglia del primo movimento per i diritti delle donne e ha significato rivendicare l'accesso a tutte le definizioni di libertà. Nel 1850 Lucy Stone organizzò un'assemblea con un focus più ampio, la National Women's Rights Convention di Worcester, nel Massachusetts. Susan B. Anthony, residente a Rochester, New York, si unì alla causa nel 1852 dopo aver letto il discorso di Stone del 1850. Stanton, Stone e Anthony furono le tre figure di spicco di questo movimento negli Stati Uniti durante il diciannovesimo secolo: il "triumvirato" che voleva ottenere diritto di voto per le donne.[137] Gli attivisti del suffragio femminile sottolinearono come fosse ingiusto che i neri non fossero inclusi negli emendamenti quattordicesimo e quindicesimo della Costituzione degli Stati Uniti che garantivano alle persone pari protezione ai sensi della legge e il diritto di voto indipendentemente dalla loro razza, rispettivamente. Le prime vittorie furono vinte nei territori del Wyoming (1869)[138] e Utah (1870).

John Allen Campbell, il primo governatore del Wyoming, approvò la prima legge nella storia degli Stati Uniti che garantiva esplicitamente alle donne il diritto di voto. La legge fu approvata il 10 dicembre 1869. Questo giorno fu in seguito commemorato come Wyoming Day.[139] Il 12 febbraio 1870, il Segretario del Territorio e il Governatore ad interim del Territorio dello Utah, S. A. Mann, approvarono una legge che consentiva alle donne di ventun anni di votare in qualsiasi elezione nello Utah.[140]

La spinta a concedere il suffragio femminile nello Utah è stata almeno in parte alimentata dalla convinzione che, con il loro voto, esse avrebbero eliminato la poligamia. Quando invece esse votarono a favore della poligamia, il Congresso degli Stati Uniti decise di privarle del diritto al voto con la legge federale Edmunds-Tucker nel 1887.[141]

Alla fine del XIX secolo, Idaho, Utah e Wyoming avevano premiato le donne dopo lo sforzo delle associazioni di suffragio a livello statale; Il Colorado, in particolare, lo fece con un referendum del 1893, mentre la California ha concesso il diritto di voto alle donne nel 1911.[142]

All'inizio del XX secolo, quando il suffragio femminile affrontò diversi importanti voti federali, una parte del movimento di suffragio noto come il Partito Nazionale della Donna guidato dal suffragista Alice Paul divenne la prima "causa" da picchettare fuori dalla Casa Bianca. Paul era stato guidato da Emmeline Pankhurst mentre si trovava in Inghilterra, e sia lei che Lucy Burns guidarono una serie di proteste contro l'amministrazione Wilson a Washington.[143]

Wilson ignorò le proteste per sei mesi, ma il 20 giugno 1917, mentre una delegazione russa si avvicinava alla Casa Bianca, i suffragisti dispiegarono uno stendardo che affermava: "Noi donne d'America vi diciamo che l'America non è una democrazia. A venti milioni di donne viene negato il diritto di voto. Il presidente Wilson è il principale oppositore della loro titolarizzazione nazionale".[144] Un altro striscione il 14 agosto 1917 si riferiva a "Kaiser Wilson" e confrontava la situazione del popolo tedesco con quella delle donne americane. Molte donne per questo furono arrestate.[145] Un'altra tattica del National Woman's Party erano gli incendi, dove venivano bruciate copie dei discorsi del presidente Wilson, spesso fuori dalla Casa Bianca o nel vicino parco di Lafayette. Il Partito ha continuato a provocare incendi anche quando è iniziata la guerra, attirando critiche da parte del pubblico e anche di altri gruppi di suffragio per non essere patriottico.[146] Il 17 ottobre Alice Paul fu condannata a sette mesi e il 30 ottobre iniziò uno sciopero della fame, ma dopo alcuni giorni le autorità carcerarie iniziarono a forzarla a mangiare.[144]Dopo anni di opposizione, Wilson cambiò posizione nel 1918 per sostenere il suffragio femminile come misura di guerra.[147]

Il voto chiave arrivò il 4 giugno 1919,[149] quando il Senato approvò l'emendamento dopo quattro ore di dibattiti, durante i quali i senatori democratici si opposero all'emendamento costituito per impedire un appello nominale fino a quando i loro senatori assenti potessero essere protetti da coppie. Gli Ayes includevano 36 repubblicani (82%) e 20 democratici (54%). I Nays comprendevano 8 repubblicani (18%) e 17 democratici (46%). Il diciannovesimo emendamento, che vietava le restrizioni statali o federali al voto basate sul sesso, fu ratificato nel 1920.[150] Secondo l'articolo "Diciannovesimo emendamento" di Leslie Goldstein, dall'Enciclopedia della Corte suprema degli Stati Uniti, "includeva anche pene detentive e scioperi della fame in carcere accompagnati da brutali alimentazioni con la forza; violenza sulla folla; e voti legislativi così vicini che i partigiani venivano portati lì su barelle" (Goldstein, 2008). Anche dopo la ratifica del diciannovesimo emendamento, le donne non smisero di avere problemi. Ad esempio, nel Maryland, quando le donne si iscrissero per votare "i residenti fecero causa per far rimuovere i nomi delle donne dal registro sulla base del fatto che l'emendamento stesso era incostituzionale." (Goldstein, 2008).

Prima del 1965 le donne di colore, come gli afroamericani e i nativi americani, erano privati del diritto di voto, specialmente al sud.[151][152]

Il Voting Rights Act del 1965 proibiva la discriminazione razziale nelle votazioni e garantiva i diritti di voto per le minoranze razziali negli Stati Uniti.[151]

Argentina[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Il moderno movimento suffragista in Argentina nacque in parte in congiunzione con le attività del Partito socialista e degli anarchici degli inizi del XX secolo. Le donne coinvolte in movimenti più ampi per la giustizia sociale hanno iniziato a richiedere pari diritti e opportunità degli uomini; seguendo l'esempio dei loro coetanei europei, Elvira Dellepiane Rawson, Cecilia Grierson e Alicia Moreau de Justo hanno iniziato a formare una serie di gruppi in difesa dei diritti civili delle donne tra il 1900 e il 1910. Le prime grandi vittorie per l'estensione dei diritti civili delle donne si è verificato nella provincia di San Juan. Alle donne era stato permesso di votare in quella provincia dal 1862, ma solo alle elezioni comunali. Un diritto simile è stato esteso nella provincia di Santa Fe, dove è stata emanata una costituzione che garantiva il suffragio femminile a livello municipale, sebbene inizialmente la partecipazione femminile ai voti fosse bassa. Nel 1927, San Juan sancì la sua Costituzione e riconobbe eguali diritti a uomini e donne. Tuttavia, il colpo di stato del 1930 cancellò questi progressi.

Una grande pioniera del suffragio femminile fu Julieta Lanteri, figlia di immigrate italiane, che nel 1910 chiese a un tribunale nazionale di concederle il diritto alla cittadinanza (all'epoca generalmente non concesso alle donne immigrate non sposate) e al suffragio. Il giudice Claros accolse la sua richiesta e dichiarò: "Come giudice, ho il dovere di dichiarare che il suo diritto alla cittadinanza è sancito dalla Costituzione, e quindi che le donne godono degli stessi diritti politici dei cittadini maschi, con le sole restrizioni determinate espressamente da tali leggi, poiché nessun abitante è privato di ciò che non viene proibito".

Nel novembre del 1911, il Dott. Lanteri fu la prima donna iberoamericana a votare. Nel 1919 fu presentata come candidata a deputata nazionale per il Partito Centro Indipendente, ottenendo 1.730 voti su 154.302.

Nel 1919, Rogelio Araya UCR Argentina era passato alla storia per essere stato il primo a presentare un disegno di legge che riconosceva il diritto di voto alle donne, una componente essenziale del suffragio universale. Il 17 luglio 1919 prestò servizio come deputato nazionale a nome del popolo di Santa Fe.

Il 27 febbraio 1946, tre giorni dopo le elezioni consacrate dal presidente Juan Perón e dalla moglie First Lady Eva Perón, 26 anni, tenne il suo primo discorso politico. In quell'occasione, Eva chiese diritti uguali per uomini e donne e in particolare il suffragio femminile:

«The woman Argentina has exceeded the period of civil tutorials. Women must assert their action, women should vote. The woman, moral spring home, you should take the place in the complex social machinery of the people. He asks a necessity new organize more extended and remodeled groups. It requires, in short, the transformation of the concept of woman who sacrificially has increased the number of its duties without seeking the minimum of their rights.»

Il disegno di legge fu presentato dal nuovo governo costituzionale immediatamente dopo il 1 maggio 1946. L'opposizione del pregiudizio conservatore era evidente, non solo nei partiti di opposizione ma anche all'interno di partiti che sostenevano il peronismo. Eva Perón ha costantemente sollecitato l'approvazione del parlamento, provocando anche proteste da parte di quest'ultimo per questa intrusione.

Il Senato approvò in via preliminare il progetto del 21 agosto 1946 e si attese oltre un anno prima che la Camera dei Rappresentanti pubblicasse il 9 settembre 1947 la Legge 13.010, che stabiliva pari diritti politici tra uomini e donne e suffragio universale in Argentina. Infine, la legge 13.010 è stata approvata all'unanimità.

In una dichiarazione ufficiale alla televisione nazionale, Eva Perón ha annunciato l'estensione del suffragio alle donne argentine:

«Women of this country, this very instant I receive from the Government the law that enshrines our civic rights. And I receive it in front of you, with the confidence that I do so on behalf and in the name of all Argentinian women. I do so joyously, as I feel my hands tremble upon contact with victory proclaiming laurels. Here it is, my sisters, summarized into few articles of compact letters lies a long history of battles, stumbles, and hope. Because of this, in it there lie exasperating indignation, shadows of menacing sunsets, but also cheerful awakenings of triumphal auroras. And the latter which translates the victory of women over the incomprehensions, the denials, and the interests created by the castes now repudiated by our national awakening. And a leader who destiny forged to victoriously face the problems of our era, General [Perón]. With him, and our vote we shall contribute to the perfection of Argentina's democracy, my dear comrades.»

Il 23 settembre 1947 fu emanata la Legge sull'iscrizione femminile (n. 13.010) durante la prima presidenza di Juan Domingo Perón, che fu attuata alle elezioni dell'11 novembre 1951, in cui 3.816.654 donne votarono (il 63,9% votò per il Partito Giustizialista e il 30,8% per l'Unione civica radicale). Più tardi nel 1952, i primi 23 senatori e deputati presero posto, rappresentando il Partito Giustizialista.

Brasile[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Alle donne fu concesso il diritto di voto e di essere elette nel Codice elettorale del 1932, seguito dalla Costituzione brasiliana del 1934. Tuttavia, la legge dello Stato del Rio Grande do Norte ha consentito alle donne di votare dal 1926.[153] La lotta per il suffragio femminile faceva parte di un movimento più ampio per ottenere diritti per le donne.[154]

Cile[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Il dibattito sul suffragio femminile in Cile iniziò negli anni '20.[155] Il suffragio femminile alle elezioni comunali fu istituito per la prima volta nel 1931 con un decreto con forza di legge; l'età di voto per le donne era fissata a 25 anni.[156][157] Inoltre, la Camera dei deputati approvò una legge il 9 marzo 1933 che istituiva il suffragio femminile alle elezioni comunali,[156] mentre il diritto di voto alle elezioni parlamentari e presidenziali avvenne in concomitanza di quelle svolte nel 1949.[155] La quota delle donne tra gli elettori è aumentata costantemente dopo tale data, raggiungendo gli stessi livelli di partecipazione degli uomini nel 1970.[155]

Mexico[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Le donne ottennero il diritto di voto nel 1947 per alcune elezioni locali e per quelle nazionali nel 1953, dopo una lotta cominciata nel XIX secolo.[158]

Venezuela[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Dopo le proteste studentesche del 1928, le donne iniziarono a partecipare più attivamente alla politica. Nel 1935, i sostenitori dei diritti delle donne fondarono il Gruppo Culturale Femminile (noto come "ACF" dalle sue iniziali in spagnolo), con l'obiettivo di affrontare i problemi delle donne. Il gruppo ha sostenuto i diritti politici e sociali delle donne e ha ritenuto necessario coinvolgerle e informarle su tali questioni al fine di garantirne lo sviluppo personale. Ha continuato a tenere seminari, oltre a fondare scuole notturne e la "House of Laboring Women" per le donne lavoratrici.

Il primo Congresso Femminile Venezuelano venne richiesto nel 1940 dai gruppi che cercavano di riformare il Codice di Condotta Civile del 1936, in collaborazione con la rappresentanza venezuelana presso l'Unione delle Donne Americane. In questo congresso, i delegati hanno discusso della situazione delle donne in Venezuela e delle loro richieste. Gli obiettivi chiave erano il suffragio femminile e una riforma del Codice di Condotta Civile. Circa dodicimila firme furono raccolte e consegnate al Congresso venezuelano, che riformò il Codice nel 1942.

Nel 1944 vennero alla luce gruppi che sostenevano il suffragio femminile, il più importante dei quali era il Feminine Action. Nel 1945 le donne ottennero il diritto di voto a livello municipale. Ciò ha spinto le donne ad agire maggiormente, per esempio il Feminine Action ha iniziato a pubblicare un giornale chiamato Correo Cívico Femenino, per collegare, informare e orientare le donne venezuelane nella loro lotta. Alla fine, dopo il colpo di stato venezuelano del 1945 e l'appello per una nuova Costituzione, il suffragio femminile divenne un diritto costituzionale nel paese.

Nelle organizzazioni non religiose[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Il diritto di voto delle donne è stato talvolta negato nelle organizzazioni non religiose; per esempio, nella National Association of the Seaf negli Stati Uniti ciò non fu possibile prima del 1964.[159]

Nella religione[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Cattolicesimo[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Il Papa è eletto dal Collegio cardinalizio.[160] Poiché le donne non sono nominate cardinali, esse non possono votare durante la scelta del Papa.[161] Gli uffici cattolici femminili della badessa o della madre superiora sono elettivi, la scelta è svolta tramite voti segreti delle suore appartenenti alla comunità.

Islam[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

In alcuni paesi, alcune moschee hanno costituzioni che vietano alle donne di votare alle elezioni consiliari.[162]

Giudaismo[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Nel Giudaismo Conservatore, nell'Ebraismo Riformato e nella maggior parte dei movimenti ebraici ortodossi le donne hanno il diritto di voto. Dagli anni '70, sempre più sinagoghe e organizzazioni religiose ortodosse moderne hanno concesso alle donne il diritto di voto e di essere elette nei loro organi di governo. In alcune comunità ebraiche Ultra-Ortodosse alle donne viene negato il voto o la possibilità di essere elette in posizioni di autorità.[163][164][165]

Notes[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

- ^ http://www.sis.gov.eg/Story/26370?lang=en-us

- ^ Simon Schama, Rough Crossings, (2006), p. 431.

- ^ LaRay Denzer, Sierra Leone: 1787–1987; Two Centuries of Intellectual Life, a cura di Murray Last, Manchester University Press, 27 January 1988, p. 442, ISBN 978-0-7190-2791-8.

- ^ a b c d e The Women Suffrage Timeline, su womensuffrage.org. URL consultato il 7 August 2015.

- ^ "Fewer Women Cast Votes In Afghanistan." Herizons 23.2 (2009): 7. Academic Search Complete. Web. 4 Oct. 2016.

- ^ Jason, Straziuso. "Afghanistan's President-Elect Promises Prominent Role, Equal Rights For Country's Women." Canadian Press, The (n.d.): Newspaper Source Plus. Web. 4 Oct. 2016.

- ^ Dilara Choudhury, and Al Masud Hasanuzzaman, "Political Decision-Making in Bangladesh and the Role of Women," Asian Profile, (Feb 1997) 25#1 pp. 53–69

- ^ (EN) Soutik Biswas, Did the Empire resist women's suffrage in India?, 22 febbraio 2018.

- ^ a b Aparna Basu, "Women's Struggle for the Vote: 1917–1937," Indian Historical Review, (Jan 2008) 35#1 pp. 128–43

- ^ Michelle Elizabeth Tusan, "Writing Stri Dharma: international feminism, nationalist politics, and women's press advocacy in late colonial India," Women's History Review, (Dec 2003) 12#4 pp. 623–49

- ^ Barbara Southard, "Colonial Politics and Women's Rights: Woman Suffrage Campaigns in Bengal, British India in the 1920s," Modern Asian Studies, (March 1993) 27#2 pp. 397–439

- ^ Basu (Jan 2008), 140–43

- ^ Blackburn, Susan, 'Winning the Vote for Women in Indonesia' Australian Feminist Studies, Volume 14, Number 29, 1 April 1999, pp. 207–18

- ^ The Fusae Ichikawa Memorial Association, su ichikawa-fusae.or.jp. URL consultato l'8 gennaio 2011 (archiviato dall'url originale il 5 marzo 2008). Retrieved from Internet Archive 14 January 2014.

- ^ (EN) The Empowerment of Women in South Korea, in JIA SIPA, 11 marzo 2014.

- ^ Apollo Rwomire, African Women and Children: Crisis and Response, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2001, 8, ISBN 978-0-275-96218-0.

- ^ Kuwaiti women win right to vote, in BBC News, 17 maggio 2005. URL consultato l'8 gennaio 2011.

- ^ Azra Asghar Ali, "Indian Muslim Women's Suffrage Campaign: Personal Dilemma and Communal Identity 1919–47," Journal of the Pakistan Historical Society, (April 1999) 47#2 pp. 33–46

- ^ Pakistani women hold 'aurat march' for equality, gender justice, su aljazeera.com.

- ^ (EN) Mehek Saeed, Aurat March 2018: Freedom over fear, su thenews.com.pk.

- ^ A rising movement, su dawn.com, 18 marzo 2019. URL consultato il 6 aprile 2019.

- ^ Errore nelle note: Errore nell'uso del marcatore

<ref>: non è stato indicato alcun testo per il marcatore:0 - ^ a b (EN) Women's Political Participation and Representation in Asia: Obstacles and Challenges, NIAS Press, 2008, p. 218, ISBN 978-87-7694-016-4. URL consultato il 23 March 2020.

- ^ (EN) Encyclopedia of Women Social Reformers, ABC-CLIO, 2001, p. 224, ISBN 978-1-57607-101-4. URL consultato il 23 March 2020.

- ^ "In Saudi Arabia, a Quiet Step Forward for Women". The Atlantic. Oct 26 2011

- ^ a b Alsharif, Asma, "UPDATE 2-Saudi king gives women right to vote", Reuters, September 25, 2011. Retrieved 2011-09-25.

- ^ Saudi monarch grants kingdom's women right to vote, but driving ban remains in force, in The Washington Post.

- ^ Saudi women vote for the first time, testing boundaries, in US News & World Report.

- ^ Saudi Arabia: First women councillors elected, 13 dicembre 2015.

- ^ Saudi voters elect 20 women candidates for the first time, in Fox News.