Ṣubḥ-i Azal: differenze tra le versioni

m apostrofo tipografico |

|||

| Riga 161: | Riga 161: | ||

=== Studi === |

=== Studi === |

||

(in ordine alfabetico) |

(in ordine alfabetico) |

||

* Abbas Amanat, ''Resurrection and Renewal, the making of the Babi Movement in Iran, 1844-1850'', Cornell University Press, Ithaca e Londra, 1989. ISBN 0-8014-2098-9 |

* {{en}} Abbas Amanat, ''Resurrection and Renewal, the making of the Babi Movement in Iran, 1844-1850'', Cornell University Press, Ithaca e Londra, 1989. ISBN 0-8014-2098-9 |

||

* Nima Wahid Azal, [http://luvah.org/pdf/four/invoking-the-seven-worlds.pdf "Invoking the Seven Worlds: An acrostic prayer by Mīrzā Yaḥyā Nūrī Ṣubḥ-i-Azal"], ''Luvah: Journal of the Creative Imagination'', Summer 2013, p. 1-37, {{ISSN|2168-6319}}. |

* {{en}} Nima Wahid Azal, [http://luvah.org/pdf/four/invoking-the-seven-worlds.pdf "Invoking the Seven Worlds: An acrostic prayer by Mīrzā Yaḥyā Nūrī Ṣubḥ-i-Azal"], ''Luvah: Journal of the Creative Imagination'', Summer 2013, p. 1-37, {{ISSN|2168-6319}}. |

||

* Fabrizio Frigerio, "Un prisonnier d'État à Chypre sous la domination ottomane : Soubh-i-Ezèl à Famagouste", in: ''Πρακτικά του Γ Διεθνούς Κυπρολογικού Συνέδριου'' (''Atti del III Congresso Internazionale di Studi Ciprioti''), Nicosia, Cipro, 2001, vol. 3, p. 629-646. |

* {{fr}} [http://plus.wikimonde.com/wiki/Fabrizio_Frigerio Fabrizio Frigerio], "Un prisonnier d'État à Chypre sous la domination ottomane : Soubh-i-Ezèl à Famagouste", in: ''Πρακτικά του Γ Διεθνούς Κυπρολογικού Συνέδριου'' (''Atti del III Congresso Internazionale di Studi Ciprioti''), Nicosia, Cipro, 2001, vol. 3, p. 629-646. |

||

* Denis MacEoin, "Division and authority claims in Babism (1850-1866)", in: ''Studia iranica'', Paris, t. 18, fasc. 1, 1989, pp. 93–129. |

* {{en}} Denis MacEoin, "Division and authority claims in Babism (1850-1866)", in: ''Studia iranica'', Paris, t. 18, fasc. 1, 1989, pp. 93–129. |

||

* Denis MacEoin, ''The Sources for Early Bābī Doctrine and History'', E.J. Brill, Leiden, 1992, ISBN 90-04-09462-8. |

* {{en}} Denis MacEoin, ''The Sources for Early Bābī Doctrine and History'', E.J. Brill, Leiden, 1992, ISBN 90-04-09462-8. |

||

* William McCants e Kavian Milani, "The History and Provenance of an Early Manuscript of the Nuqtat al-kaf Dated 1268 (1851–52)", in: ''Iranian Studies'', Settembre 2004, volume 37, n. 3, p. 431-449. |

* {{en}} William McCants e Kavian Milani, "The History and Provenance of an Early Manuscript of the Nuqtat al-kaf Dated 1268 (1851–52)", in: ''Iranian Studies'', Settembre 2004, volume 37, n. 3, p. 431-449. |

||

* Manú<u>ch</u>ihrí Sipihr, "The Practice of Taqiyyah (Dissimulation) in the Babi and Bahai Religions", in: ''Research Notes in Shaykhi, Babi and Baha'i Studies"'',1999, v.3, n°3. |

* {{en}} Manú<u>ch</u>ihrí Sipihr, "The Practice of Taqiyyah (Dissimulation) in the Babi and Bahai Religions", in: ''Research Notes in Shaykhi, Babi and Baha'i Studies"'',1999, v.3, n°3. |

||

* Manú<u>ch</u>ihrí Sipihr, "The Primal Point's Will and Testament", in: ''Research Notes in Shaykhi, Babi and Baha'i Studies'', 2004, v.7, n°2. |

* {{en}} Manú<u>ch</u>ihrí Sipihr, "The Primal Point's Will and Testament", in: ''Research Notes in Shaykhi, Babi and Baha'i Studies'', 2004, v.7, n°2. |

||

== Voci correlate == |

== Voci correlate == |

||

Versione delle 23:18, 2 feb 2016

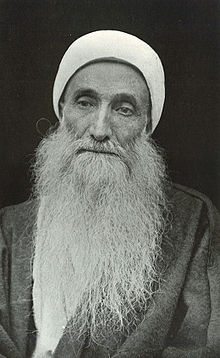

Mírzá Yaḥyá Núrí Ṣubḥ-i Azal (Aurora dell'Eternità; Teheran, 1831 – Famagosta, 29 aprile 1912) è stato un religioso persiano, figlio di Mírzá Buzurg-i Núrí e di Kúchik Khánum-i Kirmánsháhi, successore del Báb.

Nacque in un sobborgo di Teheran, in una famiglia originaria del villaggio di Tákur, nella provincia di Nur, nella regione persiana del Mazandaran, e morì a Famagosta, nell'isola di Cipro, dove era stato mandato in esilio dall'Impero ottomano nel 1868.

Biografia

Infanzia e giovinezza

A causa della prematura morte dei suoi genitori (sua madre morì alla sua nascita e suo padre nel 1839, quando aveva otto anni) si prese cura di lui Khadíja Khánum, la madre di Bahá'u'lláh[1].

Secondo la testimonianza dei suoi famigliari, fu un bambino tranquillo e molto gentile.[2] Trascorse la sua infanzia a Teheran, passando l'estate nel villaggio di Tákur, seguendo una tradizione di famiglia. Arthur de Gobineau racconta che, giunto all'età di cinque anni, la sua matrigna lo mandò a scuola, ma egli rifiutò di restarvi più di tre giorni, poiché il maestro l'aveva picchiato con un bastone.[3] Imparò la lingua persiana e fu un assai buon calligrafo, ma non gli piaceva la lingua araba.

Nel 1844, all'età di circa quattordici anni, divenne un seguace del Báb,[4] fondatore del Babismo (o fede babi) (persiano: بابی ها = Bábí há), che gli diede diversi titoli, come: Thamaratu l-Azaliyyah ("Frutto dell'Eternità") e Ismu l-Azal ("Nome dell'Eternità"). Gli Azali lo chiamarono Hadrat-i Azal ("Santità dell'Eternità") e Ṣubḥ-i-Azal ("Aurora dell'Eternità"). Quest'ultimo titolo (il suo più conosciuto) figura nei Hadith-i Kumayl,[5] il Bab lo cita nel suo libro intitolato Dala'il-i Sab'ih (Le Sette Prove). Gli Azali interpretano questa citazione come una citazione di Mírzá Yaḥyá e, contrariamente a ciò che sostengono i Baha'i[6], Manúchihri Sipihr dimostra che questo titolo fu attribuito solo a lui.[7]

All'età di sedici o diciassette anni, Ṣubḥ-i Azal sposò sua cugina Fatima Khánum. Sposò anche Maryam Khánum, conosciuta come Qaneteh, bisnonna di Atiyya Ruhi, che ha scritto la sua biografia.

Quando Ṣubḥ-i Azal volle raggiungere il Báb nel Khorasan, suo fratellastro Baha'u'llah, con la scusa della sua giovane età, l'obbligò a tornare indietro. In seguito Ṣubḥ-i Azal andò a Nur, e di là a Barfurush, dove incontrò Haji Muhammad Ali di Barfurush, che aveva accompagnato il Báb nel suo pellegrinaggio alla Mecca. Nel 1848, sempre a Barfurush, incontrò Quddús e Qurrat ul-'Ayn, sul ritorno da una grande assemblea dei Babi a Badasht. Fu poi arrestato con altri Babi mentre si preparava a raggiungere Quddús, picchiato e imprigionato.

Successione del Báb

Durante la sua prigionia nella fortezza di Chehriq, qualche tempo dopo il martirio di Quddús, il Báb scrisse nel 1849 una lettera intitolata Lawh-i Vasaya, considerata come il suo testamento, con la quale nominava Ṣubḥ-i Azal suo successore e guida della comunità babi dopo la sua morte, fino al momento in cui non sarebbe apparso "Colui che Dio renderà manifesto" (man yuẓhiruhu lláh, in arabo: من یظهر الله , e in persiano:مظهر کلّیه الهی ), con le consegne di:

- assicurare la sua propria sicurezza, quella dei suoi scritti e di tutto ciò che è rivelato nel Bayán.

- comunicare con i Babi e domandare consiglio ai Testimoni del Bayán, come pure a Áqá Siyyid Ḥusayn Yazdí.

- raccogliere e completare gli scritti santi del Báb, per poi distribuirli tra i Babi e farli conoscere all'umanità.

- invitare tutti gli uomini ad imbracciare la rivelazione del Báb.

- decidere quando sarà venuto il momento del trionfo e designare il suo proprio successore.

- riconoscere "Colui che Dio renderà manifesto" quando il verrà e invitare gli uomini a fare altrettanto.

E.G. Browne,[8] nel commento alla sua edizione della storia dei Babi di Hajj Mirza Jani di Kashan, scrive a proposito di questa nomina:

"Briefly what clearly appears from this account is that Mirza Yahya received the title of Subh-i-Azal because he appeared in the fifth year of the Manifestation, which, according to a tradition of Kumayl (p. 3, last line of the text) is characterized by "a Light which shone forth from the Dawn of Eternity"; that the Bab bestowed on him his personal effects, including his writings, clothes and rings, nominated him as his successor (Wali), and bade him write the eight unwritten Wahids of the Bayan, but abrogate it if "'He whom God', shall manifest" should appear in his time, and put into practice that with which he should be inspired."[9]

Come ha scritto A.-L.-M. Nicolas[10] "Que ce Mîrzâ Yahya [Subh-i Azal] ait été considéré par tous les bâbî comme le khalîfe du Bâb défunt, cela ne peut faire de doute pour personne et les Bèhâ'i sont de mauvaise foi quand ils le nient."[11]

Seguendo la consegna del Báb di assicurare la sua propria sicurezza, Ṣubḥ-i Azal si nascose sotto falsi nomi, praticando la dissimulazione,[12] e riuscì così a scampare alle persecuzioni che colpirono i Babi in seguito al tentato assassinio dello scià di Persia Nasser al-Din Shah Qajar(1831-1896) il 15 agosto 1852 e visse in esilio fino alla sua morte, prima a Baghdad, poi a Adrianopoli e infine a Famagosta.

Esilio a Baghdad

Ṣubḥ-i Azal era riuscito a scampare alla sanguinosa repressione dei Babi a Tákur e, sotto mentite spoglie di derviscio, ad arrivare a Bagdad, dove visse nascosto col falso nome di Ḥájí 'Alíy-i lás Furúsh, mantenendo i contatti con la comunità dei Babi tramite degli emissari chiamati "Testimoni del Bayán".[13][14] Questo volontario occultamento permise al suo fratellastro Baha'u'llah di farsi avanti e mettersi in primo piano, benché durante il loro esilio a Baghdad, Baha'u'llah riconobbe a più riprese il rango di Ṣubḥ-i Azal come capo della comunità dei Babi, almeno nei primi tempi, tanto privatamente nelle sue lettere che pubblicamente.[15] Dopo l'esecuzione del Báb il 9 luglio 1850 molti Babi dichiararono essere "Colui che Dio renderà manifesto" annunciato dal Báb, ma nessuno di loro riuscì a convincere la comunità della fondatezza delle sue pretese. Baha'u'llah pretese a sua volta aver avuto verso la fine del 1852, nella prigione sotterranea di Siyah-Chal ("il buco nero") a Teheran, un'esperienza mistica che lo rese cosciente del fatto di essere lui stesso "Colui che Dio renderà manifesto" , ma fu solamente nell'aprile del 1863 che annunciò la cosa ai suoi compagni, mentre stava per lasciare Baghdad per Costantinopoli. La maggioranza dei Babi lo riconobbero come tale e diventarono seguaci della nuova religione da lui fondata: il Bahaismo. Ma Ṣubḥ-i Azal non riconobbe la sua pretesa come fondata, e una minoranza della comunità dei Babi lo seguì e gli restò fedele, nonostante le persecuzioni di cui era vittima da parte del governo persiano ed ora pure da parte dei seguaci di Baha'u'llah.

Esilio ad Adrianopoli

Dopo un primo esilio a Baghdad fino al 1863, i capi della comunità dei Babi furono esiliati per quattro mesi a Costantinopoli, per poi essere mandati in esilio ad Adrianopoli (oggi Edirne). Durante il secondo anno di questo esilio, secondo una versione baha'i degli avvenimenti che gli Azali rifiutano come falsa e calunniatrice, Ṣubḥ-i Azal si rivoltò contro l'autorità del suo fratellastro Baha'u'llah. Intrigò presso le autorità ottomane, complottò contro Baha'u'llah e cercò pure varie volte di ucciderlo, in particolare con un veleno che gli lascio una mano tremante per il resto della sua vita. Ma molte testimonianze degne di fede mostrano al contrario che furono i Baha'i che assassinarono degli Azali.[16][17] I Baha'i sostengono che ciò accadde malgrado la proibizione formale di Baha'u'llah, il quale fu interrogato al proposito dalle autorità ottomane e rilasciato dopo aver dichiarato la propria innocenza,[18][19] ma gli Azali non accettano questa versione baha'i dei fatti e sostengono quella di Ṣubḥ-i Azal data da E.G. Browne, o una sua variante molto simile.[20]

Lo scisma della comunità dei Babi tra i seguaci di Baha'u'llah ("Baha'i") e quelli di Ṣubḥ-i Azal ("Azali") divenne ufficiale nel settembre del 1867. Baha'u'llah redasse poco dopo la sua opera intitolata Kitab-i Badi (Meraviglioso libro nuovo) per controbattere gli argomenti dei suoi avversari nel "Popolo del Bayán" (Ahl-i Bayán), soprattutto di Siyyid Muhammad-i Isfahani, che era, secondo i Baha'i, l'"eminenza grigia" di Subh-i Azal.[21]

Per capire meglio questo conflitto fratricida tra le due opposte fazioni dei Babi, bisogna ricordare che il Babismo è nato dallo sciismo duodecimano, da cui ha ripreso le nozioni di messianismo escatologico, di "Taqiya" (dissimulazione) e di "Jihad" (guerra santa) contro gli eretici,[22][23] come lo mostrano l'episodio della battaglia diShaykh Ṭabarsí[24] e il comportamento di Ṣubḥ-i Azal in esilio a Baghdad.[25][26] Bisogna anche sapere che in questa tradizione la guida religiosa non ha soltanto un'autorità spirituale, ma anche il beneficio di doni materiali che riceve dai suoi seguaci ("sihmu l-imám" : "la parte della guida").

Il conflitto tra i partigiani del Bahá'u'lláh e quelli di Ṣubḥ-i Azal divenne così violento e sanguinario che il governo ottomano decise finalmente di separarli, mandando un gruppo con Ṣubḥ-i Azal à Famagosta nell'isola di Cipro, e un altro gruppo con Bahá'u'lláh nella colonia penitenziaria di San Giovanni d'Acri (ʿAkká) in Palestina[27]. Lasciarono Andrianopoli il 12 d'agosto del 1868, (22º giorno di Rabí'u 'l-Thání 1285 E).

Esilio a Famagosta

Il 5 settembre 1868 Ṣubḥ-i Azal arrivò a Cipro con i membri della sua famiglia (due mogli, sei figli e quattro figlie, più la moglie e la figlia di suo figlio Aḥmad), alcuni discepoli e quattro Baha'i (Áqá 'Abdu l-Ghaffár Iṣfáhání, Mírzá ʿAlíy-i Sayyáh, Mishkín-Qalam et Áqá Muḥammad Báqir-i Qahvihchí),[28] che erano stati mandati a Cipro con Ṣubḥ-i Azal con lo scopo di sorvegliare da vicino i suoi movimenti e di impedire ogni possibile eventuale incontro che avrebbe potuto avere con dei Persiani di passaggio, come mostra la testimonianza di Shaykh Ibrahím raccolta da E. G. Browne.[29] Mírzá ʿAlíy-i-Sayyáh era accompagnato da sua moglie, tre figli, una figlia ed una serva, Áqá Ḥusayn-i-Iṣfáhání, dietro Mishkín-Qalam, da una serva. Mírzá ʿAlíy-i Sayyáh e Áqá Muḥammad-Báqir-i Qahvihchí morirono a Cipro nel 1871 e nel 1872, Áqá ʿAbdu l-Ghaffár Iṣfáhání riuscì a fuggire il 29 settembre|1870, mentre Mishkín-Qalam era ancora prigioniero a Famagosta con Ṣubḥ-i-Azal quando l'isola passò sotto amministrazione britannica il 22 luglio 1878, quando il Luogotenente Generale Sir Garnet Wolseley sbarcò a Larnaca per prendere possesso dell'isola di Cipro in qualità di Alto Commissario, in seguito agli accordi difensivi anglo-turchi del 4 giugno dello stesso anno.

Brillante calligrafo (da qui il suo soprannome di "Qalam", cioè "la penna, o "il pennello"), Mishkín-Qalam impartì delle lezioni di persiano a Claude Delaval Cobham,[30] che si rammaricò della sua partenza per San Giovanni d'Acri (dove andò a raggiungere i seguaci di Bahá'u'lláh) nella notte del 14 settembre 1886.

Della decina d'anni trascorsi da Ṣubḥ-i-Azal a Famagosta sotto l'occupazione ottomana - tra il 1868 e il 1878 - non rimane nessuna traccia ufficiale, i registri essendo stati persi o distrutti.[31] Durante l'occupazione inglese dell'isola, due rapporti furono scritti su di lui, il primo nel 1878 e il secondo nel 1879. Nel primo è presentato come segue:"Subbe Ezel. Handsome, well-bred looking man, apparently about 50"; mentre nel secondo si precisa che: "Has family of 17". L'atto di accusa che giustifica la sentenza d'esilio a vita è d'aver complottato contro l'Islam e la Sublime Porta.

Il 5 settembre 1879 il nuovo Alto Commissario, Sir Robert Biddulph, inviò una lettera al ministero degli affari esteri a proposito di questi prigionieri di Stato, precisando che "they are in receipt of a monthly allowance but are not permitted to leave the island". Domandò che il Governo ottomano li autorizzasse a ritornare nella loro Patria d'origine. Il 29 settembre 1879, il marchese di Salisbury, ministro britannico degli Affari esteri, incaricò E.B. Malet, rappresentante della Gran Bretagna a Costantinopoli, di occuparsi della faccenda. Questi inviò una nota in tal senso alla Sublime Porta il 10 ottobre seguente, facendo notare che "their continuance in Cyprus is a source of inconvenience to the Administration of that Island". L'amministrazione britannica dell'isola avrebbe infatti preferito fare l'economia delle rendite che erano versate a questi prigionieri; rendita che, per quel che concerne Ṣubḥ-i Azal, ammontava a 1193 piastre al mese.

La reazione delle autorità ottomane a questa richiesta fu sorprendente. Il 16 gennaio 1880, fu inviata all'ambasciata britannica a Costantinopoli una nota del ministero della Giustizia, dalla quale risulta che l'accusa portata contro Ṣubḥ-i Azal per giustificare il suo esilio non era più d'aver complottato contro l'Islam e la Sublime Porta, ma era stata cambiata in quella molto più infamante di "sodomia".[32] Il 20 gennaio dello stesso anno, una nota del ministero ottomano della Polizia, comunicata dall'ambasciata britannica di Costantinopoli a Sir Robert Biddulph (che la ricevette il 24) demandò puramente e semplicemente che Ṣubḥ-i Azal e Mishkín-Qalám fossero rimessi alle autorità ottomane per essere trasferiti come detenuti a San Giovanni d'Acri. L'accusa di sodomia contro Ṣubḥ-i Azal era mantenuta.

Messo di fronte a questa esigenza, Sir Robert Biddulph, in un rapporto al ministero degli Affari esteri dell'11 marzo 1880, fornisce tutte le informazioni al proposito che sono in suo possesso, e nota che "With regard to Subhi Ezzel, Sir R. Biddulph said that he could not discover any ground for the statement that his offense was [sodomy], his own statement being that he was falsely accused of preaching against the Turkish religion, and his bitter enemy -Muskin Kalem- also stating that the offense was heresy." Aggiunge che "they were condemned for "Babieisme" to seclusion for life in a fortress. This sentence was given by Imperial Firman and not by any judicial tribunal..." Si trattava dunque di prigionieri per un delitto d'opinione e non di condannati, riconosciuti colpevoli da un tribunale e regolarmente condannati per dei delitti di diritto comune.

In seguito a questo rapporto, il ministero degli Affari esteri diede l'ordine di liberare i due prigionieri, autorizzandoli a lasciare l'isola di Cipro se lo desideravano. Le loro rendite sarebbero state ancora pagate solo se sceglievano di continuare a restare nell'isola. Questa decisione fu comunicata alla sublime Porta, precisando che (poiché essa insisteva perché fossero trasferiti come prigionieri a San Giovanni d'Acri) i due Persiani imprigionati a Famagosta lo erano evidentemente a causa delle loro opinioni religiose, e il governo britannico non poteva trattenerveli sotto questo capo d'accusa. Il 24 marzo 1881, Ṣubḥ-i Azal fu dunque ufficialmente informato che era libero di andare dove voleva, in risposta inviò a Sir Robert Biddulph una lettera, nella quale gli domandava di poter restare sotto la protezione britannica,[33] poiché temeva di essere a sua volta assassinato dai Baha'i se andava in Palestina o dai Musulmani se tornava in Persia. Ṣubḥ-i Azal rimase dunque a Cipro, libero, e l'Impero britannico continuò a versargli la pensione che gli era stata versata fino ad allora dalla Sublime Porta ottomana come prigioniero di Stato.

Durante tutti questi anni di esilio, gli Azali vissero tra di loro e sotto stretta sorveglianza, e Ṣubḥ-i Azal non fece mai del proselitismo poiché non voleva avere di problemi col governo. Gli abitanti di Famagosta lo consideravano come un santuomo musulmano e sembrava vivere come loro.

Morte

Secondo la testimonianza di suo figlio Riḍván ʿAlí, Ṣubḥ-i Azal morì a Famagosta il lunedì 29 aprile 1912 alle ore sette del mattino e i suoi funerali si svolsero nel pomeriggio dello stesso giorno. Non essendo presente nessuno dei "Testimoni del Bayán",[34] fu sepolto secondo il rito musulmano.[35]

Famiglia

Secondo E.G. Browne, Ṣubḥ-i Azal ebbe più mogli e almeno 9 figli e 5 figlie. Suo figlio Riḍván ʿAlí sostiene che suo padre ebbe 11 o 12 mogli.[36] Altre fonti danno fino a 17 mogli, di cui 4 in Persia e almeno 5 a Bagdad, benché non sia chiaro se fosse contemporaneamente o successivamente.[37] Nabil, nella sua cronaca, di parte e anti-azali, sostiene che Subh-i Azal sposò pure in modo infamante una vedova del Bab.[38] · [39][40] Tutti questi dettagli sulla sua vita di famiglia, incerti, dubbi, improbabili e in ogni caso sospetti, sono spesso forniti dai suoi avversari baha'i, per tentare di squalificarlo moralmente.[41] È in ogni caso certo che durante gli anni del suo esilio a Cipro, dove era giunto accompagnato da due mogli (Fatima e Ruqiyya), Ṣubḥ-i Azal visse con una sola moglie,[42] la prima essendo morta subito dopo il loro arrivo nell'isola.[43]

Sempre secondo E.G. Browne, dopo la morte di suo padre, uno dei figli di Ṣubḥ-i Azal, Riḍván ʿAlí, dopo aver lasciato Famagosta per un certo periodo, si mise al servizio di Claude Delaval Cobham e si convertì all'Ortodossia col nome di "Costantino il Persiano".[44]

Successione di Ṣubḥ-i Azal

Secondo la testimonianza di Riḍván ʿAlí raccolta da E.G. Browne, nessuno dei "Testimoni del Bayán" era presente ai funerali di Ṣubḥ-i Azal, ciò che spiega la nomina di un assente come suo successore alla guida della comunità: Mirza Yahya Dawlatabadi, il figlio di Aqa Mirza Muhammad Hadi Dawlatabadi,[45] la successione era così formalmente garantita.[46]

Posterità

Dopo la sua morte i Babi deperirono durante il XX secolo, anche se alcuni ebbero un ruolo importante nella rivoluzione costituzionale persiana dal 1905 al 1911.[47] Vivevano la loro fede di nascosto in un contesto musulmano e non si dotarono mai di un sistema organizzativo su vasta scala.

Oggi rimangono solamente alcune decine di migliaia dei seguaci di Ṣubḥ-i-Azal, che si danno il nome di "Popolo del Bayán" e sono chiamati Bábí / Bayáni / Azalí, specialmente in Iran e in Uzbekistan,[48] ma è impossibile dare una cifra esatta, poiché continuano a praticare la dissimulazione (taqīya) e vivono senza distinguersi dai musulmani che li circondano. Alcuni si sono stabiliti negli Stati Uniti d'America,[49] dove recentemente sono stati ripubblicati gli scritti di August J. Stenstrand in difesa di Ṣubḥ-i-Azal, pubblicati per la prima volta tra il 1907 e il 1924.[50]

Opere

Ṣubḥ-i Azal ha lasciato un importante numero di scritti, la maggior parte dei quali non sono mai stati tradotti. Alcuni di questi testi sono pubblicati nella lingua originale (persiano o arabo) sul sito della Religione del Bayán. In traduzione inglese si può leggere il Risalij-i Muluk (Trattato sulla Regalità), scritto nell'agosto del 1895, in risposta ad alcune domande che gli erano state fatte da A.-L.-M. Nicolas.

Obbedendo agli ordini del Báb, Ṣubḥ-i Azal ha completato il Bayān persiano(traduzione in francese). Il Bab non completò i suoi due Bayán (l'arabo e il persiano), che avrebbero dovuto essere composti da 19 "Unità" (wahid, il cui valore numerico equivale a 19 secondo la numerazione Abjad), composte da 19 capitoli (o "Porte" = abwāb, singolare = bāb), il numero 19 avendo nel Babismo un importante ruolo simbolico, come pure il numero 361 (19x19 Kull-i-Shay' = "Totalità", il cui valore numerico equivale a 361). Il Bayán persiano è formato da 9 unità complete e da 10 capitoli (o Porte), mentre il Bayān arabo da 11 unità complete. Sia Ṣubḥ-i Azal sia Baha'u'llah si arrogarono il diritto di completare il Bayān, ma né l'uno né l'altro scrissero un libro corrispondente al progetto iniziale del Bab. Ṣubḥ-i Azal scrisse un'opera intitolata Motammem al-Bayán (Supplemento al Bayán) per dare al Bayán persiano lo stesso numero di unità complete del Bayán arabo. Baha'u'llah scrisse nel 1862 il suo Kitāb-i Iqan (Libro della Certezza), considerato dai Baha'i come il complemento del Bayán rivelato da "Colui che Dio renderà manifesto" annunciato dal Báb.

Note

- ^ Atiyya Ruhi, A Brief Biography of His Holiness Subh-i Azal

- ^ "The signs of his natural excellence and goodness of disposition were apparent in the mirror of his being. He ever loved gravity of demeanour, silence, courtesy, and modesty, avoiding the society of other children and their behaviour." The Tarikh-i Jadid, or New History of Mirza 'Ali Muhammad the Bab, by Mirza Huseyn of Hamadan, translated from the persian by E. G. Browne, Cambridge, 1893, Appendix II, Havji Mirza Jani's History, with especial reference to the passages suppressed or modified in the Tarikh-i Jadid, p. 375.

- ^ Religions et philosophies dans l'Asie Centrale, Ernest Leroux éd., Parigi, 3ª ed., 1900.

- ^ Denis MacEoin, op. cit. in bibliografia.

- ^ Detti di Maometto, considerati come "santi" dai musulmani.

- ^ Tablet of the Báb Lawh-i-Vasaya, "Will and Testament" and Titles of Mírzá Yahyá, mémorandum del 28 maggio 2004, redatto dal Dipartemento di Ricerca del Centro mondiale baha'i su richiesta della "Casa Universale di Giustizia"

- ^ "The Primal Point’s Will and Testament", scritto da Manuchihri Sipihr e pubblicato in Research Notes in Shaykhi, Babi and Baha'i Studies, 2004, v. 7, n° 2 :"The tablet is clearly addressed to the person with the name of Azal. As there was no one else with such a title in the Babi community, it can safely be assumed that the intended recipient of this tablet is none other than Subh-e Azal."

- ^ Nato il 7 febbraio 1862 e morto il 25 gennaio 1926, Edward Granville Browne studiò a Eton e a Cambridge il persiano, l'arabo e il sanscrito. È stato uno dei più celebri orientalisti britannici ed è stato professore all'Università di Cambridge, dove ha creato una scuola di lingue orientali viventi. Arrivò in Persia nell'ottobre del 1887 e ha descritto i suoi viaggi nel suo libro intitolato A Year amongs the Persians 1893. Ha scritto molti libri e articoli sul Babismo e la religione Baha'i. Ha incontrato personalmente tanto Baha'ullah quanto Ṣubḥ-i Azal, come pure ʿAbd ul-Bahá, col quale ha avuto uno scambio epistolare, e del quale ha scritto una necrologia nel 1921.

- ^ Kitab-i Nuqtatu l-Kaf Being the Earliest History of the Babis compiled by Hajji Mirza Jani of Kashan between the years A.D. 1850 and 1852, edited from the unique Paris MS. Suppl. Persan 1071 by Edward G. Browne, p. 20

- ^ Séyyèd Ali Mohammed dit le Bâb, Parigi, 1905, p. 20

- ^ La questione è stata definitivamente chiarita da Denis MacEoin, "Division and authority claims in Babism (1850-1866)", in: Studia iranica, Parigi, t. 18, fasc. 1, 1989, pp. 93-129.

- ^ Cf. Manúchihrí Sipihr, "The Practice of Taqiyyah (Dissimulation) in the Babi and Bahai Religions", Research Notes in Shaykhi, Babi and Baha'i Studies, 1999, v. 3, n° 3.

- ^ Denis MacEoin,"Division and authority claims in Babism (1850-1866)", Studia iranica, Parigi, t. 18, fasc. 1, 1989, pp. 93-129.

- ^ Cambiando spesso di identità, di professione e di luogo di residenza, Ṣubḥ-i Azal non faceva altro che seguire le raccomandazioni del Báb, nascondendosi per sfuggire alle persecuzioni.Vedi: Adib Taherzadeh, La Révélation de Baha'u'llah, volume 1, chapitre 15, Maison d'Editions Bahá'íes, Bruxelles.

- ^ "Baha'u'llah's Surah of God: Text, Translation, Commentary", tradotto da Juan Cole, Translations of Shaykhi, Babi and Baha'i Texts, 2002, vol. 6, n° 1.

- ^ "At first now a few prominent Babis, including even several "Letters of the Living" and personal friends of the Bab, adhered faithfully to Subh-i-Ezel. One by one these disappeared, most of them, as I fear cannot be doubted, by foul play on the part of too zealous Beha'is. Haji Seyyid Muhammad of Isfahan, one of the Bab's "Companions" (aṣhab). Mirza Riza-Kuli and his brother Mirza Nasru'llah of Tafrish, Aka Jan Beg of Kashan, and other devoted Ezelis, were stabbed or poisoned at Adrianople and Acre. Two of the "Letters of the Living", Aka Seyyid 'Ali the Arab, and Mulla Rajab 'Ali Kahir, were assassinated, the one at Tabriz, the other at Kerbela. The brother of the latter, Aka 'Ali Muhammad, was also murdered in Baghdad; and, indeed, of the more prominent Babis who espoused the cause of Ezel, Seyyid Jawad of Kerbela (who died at Kirman about 1884) seems to have been almost the only one, with the exception of Ezel himself, who long survived what the Ezelis call "the Direful Mischief" (fitna-i saylam)." The Tarikh-i Jadid, or New History of Mirza 'Ali Muhammad the Bab,scritta da Mirza Huseyn d'Hamadan, tradotta dal persiano in inglese da E. G. Browne, Cambridge, 1893, pp. XXIII-XXIV.

- ^ "Just before the departure [for Cyprus and Acre], Mirza Nasrullah of Tafresh was poisoned by Bahaâ's men. The other three followers of Subh-i Azal were murdered by Bahaâ's men and at his behest shortly after their arrival in Acre. The Ottoman officials arrested the murderers and imprisoned them. These were released after a while after Abbas Effendi (Bahaâ's eldest son) interceded. Professor Browne has confirmed the murder of the Azalis at the hands of Bahais in his book A Year Amongst the Persians". Atiyya Ruhi, "A Brief Biography of His Holiness Subh-i Azal".

- ^ "Bien qu'il eût rigoureusement interdit à ses fidèles, à plusieurs reprises, toute action de représailles, verbale ou écrite, contre leurs bourreaux - il avait même renvoyé à Beyrouth un Arabe converti, irresponsable, qui méditait de venger les torts soufferts par son chef bien-aimé -, sept de ses compagnons recherchèrent et tuèrent clandestinement trois de leurs persécuteurs, parmi lesquels Siyyid Muhammad et Àqà Jàn. La consternation qui s'empara d'une communauté déjà accablée fut indescriptible. L'indignation de Bahá'u'lláh ne connut plus de bornes. Dans une tablette révélée peu de temps après cet acte, Bahá'u'lláh exprime ainsi son émotion: "S'il nous fallait raconter tout ce qui nous est arrivé, les cieux se fendraient et les montagnes s'écrouleraient." "Ma captivité", écrit-il ailleurs, "ne peut me faire de mal. Ce qui peut me faire du mal, c'est la conduite de ceux qui m'aiment, qui se réclament de moi et qui, pourtant, commettent ce qui fait gémir mon cœur et ma plume." Et il ajoute: "Ma détention ne peut m'apporter aucune honte. Et même, par ma vie, elle me confère de la gloire. Ce qui peut me faire honte, c'est la conduite de ceux de mes disciples qui font profession de m'aimer et qui, en fait, suivent pourtant le malin. Il était en train de dicter ses tablettes à son secrétaire lorsque le gouverneur arriva à la tète de ses troupes qui, sabres au clair, entourèrent sa demeure.[...] Bahá'u'lláh fut convoqué d'une manière impérative au siège du gouvernement, interrogé et détenu la première nuit, avec l'un de ses fils, dans une chambre du Khàn-i-Shàvirdi; transféré pour les deux nuits suivantes dans un logement plus convenable, au voisinage, il ne fut autorisé à regagner son domicile que soixante-dix heures plus tard. […] "Est-il convenable", s'enquit avec insolence le commandant de la ville, se tournant vers Bahá'u'lláh lorsqu'il arriva au siège du gouvernement, "que certains de vos disciples se conduisent de la sorte?', "Si l'un de vos soldats", répliqua promptement Bahá'u'lláh, "Commettait un acte répréhensible, seriez-vous tenu pour responsable et puni à sa place?". Lors de son interrogatoire, on lui demanda de décliner son nom et celui du pays d'où il venait. "Ceci est plus évident que le soleil', répondit-il. On lui posa de nouveau la même question à laquelle il donna cette réponse: "je ne juge pas à propos d'en parier. Reportez-vous au farmàn du gouvernement qui se trouve entre vos mains." Une fois de plus, avec une déférence marquée, ils réitérèrent leur demande, sur quoi Bahá'u'lláh prononça, avec puissance et majesté, ces paroles: "Mon nom est Bahá'u'lláh" (Lumière de Dieu), "et mon pays est Nour" (Lumière). "Soyez-en informés." Se tournant alors vers le mufti, il lui adressa des reproches voilés, puis il parla à toute l'assemblée dans un langage si véhément et si élevé que nul n'osa lui répondre. Après avoir cité des versets de la Sùriy-i Mùlùk, il se leva et quitta l'assemblée. Aussitôt après, le gouverneur lui fit savoir qu'il était libre de retourner chez lui, en exprimant ses regrets pour ce qui s'était passé." citazione di "Dieu passe près de nous", pp. 181-183 cap. XI

- ^ "Well, one night about a month after their arrival at Acca, twelve Bahais (nine of whom were still living when I was at Acca) determined to kill them and so prevent them from doing any mischief. So they went at night, armed with swords and daggers, to the house where the Azalis lodged, and knocked at the door. Aga Jan came down to open to them, and was stabbed before he could cry out or offer the least resistance. Then they entered the house and killed the other six. In consequence, the Turks imprisoned Baha and all his family and followers in the caravanserai, but the twelve assassins came forward and surrendered themselves, saying, ' We killed them without the knowledge of our Master or of any of the brethren. Punish us, not them.'" citazione da "Bahaism and Religious assassination" di S.G. Wilson in Muslim World, Volume 4, Issue 3, p. 236, Londres, 1914 (Published for The Nile Mission Press by the Christian Litérature Society for India 35 John Street, Bedford Row, W.C.)

- ^ "The Baha'i religion has not proven to be very paceful in its propagation so far. Its own history proves the contrary! The early Bábis waged war openy against their opponents, and when Bahá'[u'lláh] declared himself to be head of the movement it became a secret warfare by assassinating his opponents with either poison, bullet or dagger,: no less than twenty of the most learned and oldest of the Bábis, including many of the original "Letters of the Living", where thus removed. It was said that Bahá'[u'lláh] did not order these assassinations. No, but he was well pleased with them, and the perpetrators , for be promoted them to higher names and ranks. One of them received the following encouragement from Bahá'[u'lláh] for stealing £ 350 in money from one of his antagonists: "O phlebotomist of the Divine Unity! Throb like the artery in the body of the Contingent World, and drink of the blood of the "Block of Heedlessness" for that he turned aside from the aspect of thy Lord the Merciful!" August J. Stenstrand, The Complete Call to the Heaven of the Bayan, Chicago, 2006, p. 112 (pubblicato per la prima volta nel giugno 1913)

- ^ Logos and Civilization, scritto da Nader Saiyyedi e pubblicato dalla University Press of Maryland, USA, 2000, chap. 6, ISBN 1-883053-60-9

- ^ "On the other hand, Babi doctrines maintain their traditional bond to Shii Islam, as is the case with taqiya, the possibility of hiding one’s religious thoughts or convictions in times of crisis or danger. The idea of martyrdom and warlike jihad as a means to reach salvation also remain central in Babi thought." "An introduction to Bab'i faith", in Encyclopedia of religion, ed. da Lindsay Jones, Ed.Macmillan Reference, USA, 2004, 2 edizione (Dicembre 17) ISBN 0-02-865733-0

- ^ "The practice of Taqiya (Dissimulation) in Babi and Bahai religions" di Sepehr Manuchehri, Research Notes in Shaykhi, Babi and Baha'i Studies, 1999, Settembre, Vol. 3, no. 3.

- ^ La rivolta dei Babi nel Mazandaran e l'episodio di Shaykh Tabarsi sono la prova che essi consideravano come legittima il "Jihad bi-sayf" ("Jihad con la spada"), poiché questo combattimento fu ingaggiato su ordine dello stesso Báb, con evidenti implicazioni escatologiche.

- ^ Mutatis mutandis, i decreti (fatwa ) di morte che emanò contro alcuni Babi che si opponevano alla sua autorità come successore del Báb alla guida della comunità possono essere considerati come una forma di "Jihad bi-sayf" (jihad armato) e comparati alle "guerre contro l'apostasia" (hurub al-ridda) che Abu Bakr al-Siddiq intraprese contro coloro che contestavano la sua autorità di Califfo dopo la morte di Maometto. Su queste "fatwa", si può leggere Extracts from the memoirs of Nabil Zarandi on the conduct of the Babis in Iraq, prefazione e traduzione di Sepehr Manuchehri, e l'episodio del Dayyan in:"The Messiah of Shiraz" (Studies in early and middle Babism), di Denis MacEoin, Iran Studies, Vol. 3, p. 389-391 (The episode of Dayyan) ISBN 978-90-04-17035-3

- ^ "C’était seulement naturel, dans les circonstances d’espoir frustré et de douleur montante, et en vue de la promesse claire et énergique donnés à eux par le Bab, en regard de l’avènement proche de «Celui que Dieu rendra manifeste», que nombre d’entre eux durent presque faire un pas en avant dans un état d’auto-hypnotisme, de revendiquer être Celui pour (whose sake) le Bab avait joyeusement versé Son sang, de proclamer qu’ils étaient venus pour sauver une communauté étourdie par l’adversité des abysses du désespoir et de la dégradation. Une nouvelle fois, il était naturel qu’ils puisent trouver des adhérents, que certains se rallieraient avec joie autour d’eux, car c’était une main guide, un sage conseiller dont les babis avaient désespérément besoin. A peine quelques uns de ces «Manifestations de Dieu» auto nommées étaient des hommes de ruse, d’avidité ou d’ambition. Alors que les tensions augmentaient, leur nombre s’éleva au nombre élevé de 25. L’un d’entre eux était un indien nommé Siyyid Basir, un homme d’un courage sans bornes et zélé, qui finalement rencontra la mort comme martyre. Un prince obstiné de la maison de Kadjar s’infligea des tortures atroces sur lui auxquelles il succomba. Un autre était Mirza Asadu’llah de Khuy, que le Bab avait nommé Dayyan, connu comme la «troisième Lettre à croire en Celui que Dieu rendra manifeste». Le Bab s’était même référé à lui comme le dépositaire de la vérité et de la connaissance de Dieu. Au moment où Baha’u’llah avait quitté Bagdad pour résider dans les montagnes du nord, Dayyan approcha Mirza Yahya et fut grandement déçu. Puis il avança la revendication de son propre chef, à l’appui de quoi il écrivit un traité et envoya une copie à Mirza Yahya. La réponse de Subh-i-Azal fut de le condamner à mort. Il écrivit un livre qu’il appela Mustayqiz( L'endormi réveillé) (dont il y a des copies au British Museum) pour dénoncer Dayyan et Siyyid Ibrahim-i-Khalil, un autre important Babi, qui s’était aussi détourné de lui. Dayyan fut fustigé comme "Abu’sh-Shurur" - le "Père des iniquités". E. G. Browne écrit au sujet de cette accusation : "Ṣubḥ-i-Azal [...] non seulement l’insulte dans le langage le plus grossier, mais il exprime sa surprise que ses adhérents 'restent silencieux à leurs places et ne le transpercent pas avec leurs lances', ou 'ne déchirent pas ses intestins avec leurs mains'". Materials for the Study of the Babi Religion, Cambridge, 1918, p. 218. Lorsque Baha’u’llah revint à Bagdad, Dayyan le rencontra et renonça à sa revendication. Mais la sentence de mort prononcée par Ṣubḥ-i-Azal fut exécutée par son serviteur, Mirza Muhamad-i-Mazindarani. Mirza Ali-Akbar, un cousin du Bab, qui était dévoué à Dayyan, fut aussi tué. (cf. H. M. Balyuzi, 'Edward Granville Browne and the Bahá'í Faith, Oxford, George Ronald editore , ISBN 0-85398-023-3 )

- ^ "Dissensions naturally arose, which culminated in the interference of Turkish government and the final separation of the rival heads. Subh-i-Azal was sent to Famagusta in Cyprus, and Baha'ullah to Akka in Palestine, and there they remain to the present day , the former surrounded by a very few, the latter by many devoted adherents. Less than a year ago I visited both places , and heard both sides of a long and tangled controversy. But the upshot of the whole matter is, that out of every hundred Bábis probably not more than three or four are Azalis, all the rest accepting Baha'ullah as the final and most perfect manifestation of the Thruth." E. G. Browne, "Bábism", in: August J. Stenstrand, The Complete Call to the Heaven of the Bayan, Chicago, 2006, pp. 49-50

- ^ Lista degli esiliati nel rapporto di E.G. Browne sul viaggio da San Giovanni d'Acri a Cipro (Browne Papers, manoscritti d Browne alla biblioteca dell’università di Cambridge, Sup 21(8), p. 20; come corretto nella traduzione fatta da E.G. Browne di A Traveller's Narrative written to illustrate the Episode of the Báb, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1891, vol. 2, pp. 376-389.

- ^ "[...] Mushkin-Kalam set up a little coffee-house at the port where travellers must needs arrive, and whenever he saw a Persian land, he would invite him in, give him tea or coffee and a pipe and gradually worm out of him the business which had brought him thither. And if his object were to see Subh-i-Ezel, off went Mushkin-Kalam to the authorities, and the pilgrim soon found himself packed out of the island." A Traveller's Narrative written to illustrate the Episode of the Báb, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1891, vol. 2, pp. 560-561.

- ^ Nato nel 1842 e morto nel 1915, studiò a Oxford (B.A. Hon. 1866, B.C. L., M.A. 1869, aggiunto del commissario (1878) e poi(1878-1907) commissario di Larnaca, autore di An Attempt at a Bibliography of Cyprus, Nicosia, 1886 (5ª ed. Cambridge, 1908) e di Excerpta Cypria, Cambridge, 1908 (2ª ed.), cf. Αριστἱδις Κουδυουνἁρις, Βιογραφικὁν Λεχικὁν Κυπρἱον [Dizionario biografico dei Ciprioti], Nicosia, 1991, p. 96, sub voce.

- ^ Per tutto ciò che concerne la sua vita a Famagosta cf. Fabrizio Frigerio, "Un prisonnier d'État à Chypre sous la domination ottomane : Soubh-i-Ezèl à Famagouste", in: Πρακτικά του Γ Διεθνούς Κυπρολογικού Συνέδριου (Atti del III Congresso Internazionale di Studi Ciprioti), Nicosia, Cipro, 2001, vol. 3, pp. 629-646.

- ^ Ciò che sembra alquanto strano se si pensa che nello stesso tempo, per cercare di squalificarlo moralmente, i suoi avversari baha'i l'hanno accusato d'aver avuto fino a diciassette mogli, cf. "The Cyprus Exiles", scritto da Moojan Momen e pubblicato in Bahá'í Studies Bulletin, 1991, pp. 81-113.

- ^ "To the Commissioner, I have received your kind letter of 24/4/81 and indeed I cannot express my feelings of gratitude to H.M. the Queen and to the Heads of the English Govt. in Cyprus. I thank you sincerely, Sir, for the kind letter you had sent me releasing me from my exile here, and wish long life to H.M. the Queen. Another small favour I should like to ask, if it is possible that I might be in future under English protection, as I fear that going to my country my countrymen might again come on me. My case was simple heretic religious opinions, and as the English Govt. leaves free every man to express his own opinions and feelings on such matters, I dare hope that this favour of being protected by them, and which favour I most humbly ask, will not be refused to me. (signed) Subhi Ezzel." (Browne Papers, Folder 6, Item 7, No 21)

- ^ "But none were to be found there of witnesses to the Bayan"

- ^ "His household and its members applied to the government and asked permission from the Governor [i.e. Commissioner] of Famagusta to deposit his body in a place who belonged to that Blessed Being and which is situated about one European mile outside Famagusta near to the house of Baruvtji-zada Haji Hafiz Efendi. His Excellency the Commissioner granted his permission with the utmost kindness and consideration, and a grave was dug in that place and built up with stones. A coffin was then constructed and prepared, and in the afternoon all the government officials, by command of the Commissioner, and at their own wish and desire, together with a number of people of the country, all on foot, bore the corpse of that Holy being on their shoulders, with pious ejaculations and prayers, and every mark of extreme respect, from his house to the site of the Holy Sepulchre. But none were to be found there of witnesses to the Bayan, therefore the Imam-Jum'a of Famagusta and some others of the doctors of Islam, having uttered [the customary] invocations, placed the body in the coffin and buried it. And when they brought it forth from the gate of Famagusta some of the Europeans also accompanied the Blessed Body, and the son of the Quarantine doctor took a photograph of it with a great number [of the bystanders], and again took another photograph at the Blessed Tomb.", "Account of the Death of Mirza Yahya Subh-i-Azal", tradotto da E.G.Browne e pubblicato in Materials for the Study of the Babi Religion, p. 311-312. Le due fotografia scattate durante i funerali dal figlio del medico della quarantena sono state pubblicate da Harry Charles Lukach [diventato poi Sir Harry Luke], The Fringe of the East, A Journey through Past and Present Provinces of Turkey, Londres, MacMillan and Co., 1913, di fronte alla p. 266, con un ritratto fotografico di Ṣubḥ-i Azal all'età di 80 anni, di fronte alla p. 264.

- ^ E.G. Browne, "Personal Reminiscences of the Babi Insurrection at Zanjan in 1850, scritto da Aqa ʿAbdu'l-Ahad-i-Zanjani", Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, 1897, pp. 761-827) p. 767.

- ^ "The Cyprus Exiles", scritto da Moojan Momen e pubblicato in "Bahá'í Studies Bulletin", vol. 5, no. 3 - vol. 6, no. 1, Giugno 1991, pp. 84-113.

- ^ "God passes by" di Shoghi Effendi alla p. 165

- ^ "A Critical Analysis di "God passes by" scritto da Imran Shaykh, vedere il capitolo su "The Decline of Mirza Yayha and His Subsequent Deeds"

- ^ "He ordered the wife of the Bab, [Fatimah Khanum, the sister of Mulla Rajab-Ali Qahir. She was the temporary wife (Siqah) of the Bab in Isfahan] to arrive in Baghdad from land of Sad, [Means the city of Isfahan in Babi terminology] with hundred treachery and contempt, he took her for one full month, afterwards he gave her away, to that bastard Dajjal from land of Sad.",Extracts from the memoirs of Nabil Zarandi on the conduct of the Babis in Iraq', prefazione e traduzione di Sepehr Manuchehri

- ^ L'albero genealogico dettagliato del sito azali gli attribuisce 5 mogli: Badr-i Jahan, Ruqiyya, Maryam, Kulk-i Jahan et Fatima.

- ^ Fabrizio Frigerio, "Un prisonnier d'État à Chypre sous la domination ottomane: Soubh-i-Ezèl à Famagouste", Πρακτικά του Γ Διεθνούς Κυπρολογικού Συνέδριου [Atti del III Congresso Internazionale di Studi Ciprioti], Nicosia, Cipro, 2001, vol. 3, pp. 629-646.

- ^ "Died, apparently soon after arrival." E.G. Browne, A Traveller's narrative written to illustrate the Episode of the Bab, Cambridge, 1891, vol. II, p. 384.

- ^ The Cyprus Exiles" di Moojan Momen, in Bahá'í Studies Bulletin, 1991, p. 99.

- ^ "Now this Holy Person [i.e. Subh-i Azal] before his death had nominated [as his executor or successor] the son of Aqa Mirza Muhammad Hadi of Dawlatabad, who was one of the leading believers and relatively better than the others, in accordance with the command of His Holiness the Point [i.e. the Bab], glorious in his mention, who commanded saying, “And if God causeth mourning to appear in thy days, then make manifest the eight Paths,“ etc. until he says, “But if not, then the authority shall return to the Witnesses of the Bayan “."

- ^ Il successore designato da Ṣubḥ-i Azal, nato nel 1862-63, è morto nel 1940. Secondo Denis MacEoin: "Yahyâ, however, devoted his energies to education and literature and seems to have had little to do with Babism." (The Sources for Early Bâbî Doctrine and History, A survey, Leiden, 1992, p. 38, nota 125).

- ^ "The small but influential circle of Azalī Babis and their sympathizers included at least six major preachers of the Constitutional Revolution. By the beginning of the 20th century the separation of the Bahai majority and the Azalī minority was complete. The Babis, loyal to the practice of dissimulation (taqīya), adopted a fully Islamic guise and enjoyed a brief revival during the reign of Moẓaffar-al-Dīn Shah. As they broadened their appeal beyond the Babi core, a loose network of assemblies (majles) and societies (anjomans) gradually evolved into a political forum in which both clerical and secular dissidents who favored reform were welcome. These radicals remained loyal to the old Babi ideal of mass opposition to the conservative ʿolamāʾ and Qajar rule. An example of their approach is Roʾyā-ye ṣādeqa, a lampoon in which the notorious Āqā Najafī Eṣfahānī is tried on Judgment Day; it was written by Naṣr-Allāh Beheštī, better known as Malek-al-Motakallemīn, and Sayyed Jamāl-al-Dīn Wāʿeẓ Eṣfahānī, two preachers of the constitutional period with Babi leanings. Such figures as the celebrated educator and political activist Mīrzā Yaḥyā Dawlatābādī; Moḥammad-Mahdī Šarīf Kāšānī, a close advisor to Sayyed ʿAbd Allāh Behbahānī and chronicler of the revolution; and the journalist Mīrzā Jahāngīr Khan Ṣūr-e Esrāfīl shared the same Babi background and were associated with the same circle." Lemma «Constitutional revolution, i. Intellectual background», Encyclopaedia Iranica

- ^ Articolo in inglese dell’Encyclopaedia of the Orient.

- ^ Blog azali in inglese.

- ^ The Complete Call to Heaven of the Bayán, scritto da August J. Stenstrand, edito da Muhammad Abdullah al-Ahari con un'introduzione di G. E. Browne sul Babismo e pubblicato da Magribine Press, Chicago, 2006, ISBN 978-1-56316-953-3.

Bibliografia

(in ordine cronologico)

Fonti

- E. G. Browne

- "Kitab-i Nuqtatu'l-Kaf", Being the Earliest History of the Babis, scritta da Hajji Mirza Jani di Kashan tra il 1850 e il 1852, edita da E. G. Browne.

- "A Traveller's Narrative: Written to illustrate the episode of the Bab", scritto da `Abdu'l-Bahá, tradotto da E.G. Browne (1886) e ripubblicato da Kalimát Press, Los Angeles, 2004, con note del traduttore), ISBN 1-890688-37-1

- A Year Amongst the Persian, scritto da E. G. Browne, pubblicato da A & C Black Ltd, Londra, 1893.

- "A Traveller's Narrative: Written to illustrate the episode of the Bab", scritto da `Abdu'l-Bahá, tradotto da E.G. Browne e pubblicato da Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1891 (vedere l'introduzione e le note (w) di Browne)

- "Personal Reminiscences of the Babi Insurrection at Zanjan in 1850", scritto da Aqa 'Abdu'l-Ahad-i-Zanjan, tradotto da E.G. Browne e pubblicato inJournal of the Royal Asiatic Society, 1897, v. 29, p. 761–827

- 'Materials for the Study of the Bábí Religion, scritto da E.G. Browne (1918), pubblicato da Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Michele Lessona

- I Babi scritto da Michele Lessona (Torino, Ermanno Loescher ed., 1881). Pubblicazione digitalizzata di East Lansing, Mi., H-Bahai, 2003.

- Clément Huart

- La religion de Bâb, Réformateur persan du XIXe siècle, scritto da Clément Huart, Ernest Leroux ed., Parigi, 1889.

- Arthur de Gobineau

- Religions et philosophies dans l'Asie Centrale, scritto da Arthur de Gobineau e pubblicato da Ernest Leroux, Parigi, 3ª edizione, 1900.

- A.-L.-M. Nicolas

- Le Livre de Sept Preuves de la Mission du Bab. Tradotto da Louis Alphonse Daniel Nicolas (A.-L.-M.) e pubblicato dalla Librairie Orientale et Americaine, Parigi, 1902. (Reprinted. East Lansing, MIchigan, H-Bahai, 2004.

- Seyyed Ali Mohammad dit le Báb, scritto da A.-L.-M. Nicolas, pubblicato da Dujarric & Cie Éditeurs, Parigi, 1905.

- Le Beyan Arabe. Le Livre Sacré du Babysme scritto da Seyyed Ali Mohamed detto il Bab. Tradotto dall'Arabo da Louis Alphonse Daniel Nicolas, (A.-L.-M.), Parigi, Ernest Leroux, 1905. Reprinted. East Lansing, Michigan, H-Bahai, 2004.

- Le Beyan Persan scritto da Seyyed Ali Mohmmed detto il Bab, tradotto da Louis Alphonse Daniel Nicolas (A.-L.-M.) et édité par la Librairie Paul Geuthner, Paris, 1911, 1913, 1914. Reprinted East Lansing, MIchigan, H-Bahai, 2004.

- Qui est le successeur du Bâb? , scritto da A.-L.-M. Nicolas, pubblicato da Adrien Maisonneuve, Parigi, 1933.

- Les Behahis et le Bab, scritto da A.-L.-M. Nicolas e pubblicato dalla Librairie Orientaliste Paul Geuthner, Parigi, 1933. Reprinted. East Lansing, Michigan, H-Bahai, 2010.

- Massacres de Babis en Perse, scritto da A.-L.-M. Nicolas e pubblicato dalla Librairie d'Amerique et d'Orient, Parigi, 1936. Reprinted East Lansing, Michigan, H-Bahai, 2010.

Scritti di Azali

- A Brief Biography of His Holiness Ṣubḥ-i-Azal, scritto da 'Aṭṭíya Rúḥí.

- The Complete Call to Heaven of the Bayan, scritto da August J. Stenstrand, edito da Muhammad Abdullah al-Ahari con un'introduzione di G. E. Browne sul Babismo e pubblicato dalla Magribine Press, Chicago, 2006, ISBN 978-1-56316-953-3.

- The Bahá'í Faith: Its History and Teachings, scritto da William McElwee Miller, pubblicato dalla William Carey Library, Pasadena, CA, 1974. ISBN 0-87808-137-2.

Scritti di Bahai

- "The Dawn-Breakers: Nabíl's Narrative", scritto in persiano alla fine del XIX secolo da Muḥammad-i-Zarandí (Nabíl-i-A'ẓam), tradotto in inglese da Shoghi Effendi e pubblicato da Bahá'í Publishing Trust, Wilmette, (Illinois, USA), 1932, ISBN 0-900125-22-5

- My Memories of Bahá'u'lláh, scritto da Ustád Muḥammad-'Alíy-i-Salmání e pubblicato da Kalimát Press, Los Angeles, 1982.

- God Passes By (Dio passa vicino a noi), scritto da Shoghi Effendi e pubblicato da Bahá'í Publishing Trust, Wilmette, (Illinois, USA), 1944, ISBN 0-87743-020-9.

- "The Cyprus Exiles", scritto da Moojan Momen e pubblicato in Bahá'í Studies Bulletin, 1991, p. 81-113.

- "Baha'u'llah's Surah of God : Text, Translation, Commentary", tradotto da Juan Cole e pubblicato in Translations of Shaykhi, Babi and Baha'i Texts, 2002, vol. 6, n° 1.

Studi

(in ordine alfabetico)

- (EN) Abbas Amanat, Resurrection and Renewal, the making of the Babi Movement in Iran, 1844-1850, Cornell University Press, Ithaca e Londra, 1989. ISBN 0-8014-2098-9

- (EN) Nima Wahid Azal, "Invoking the Seven Worlds: An acrostic prayer by Mīrzā Yaḥyā Nūrī Ṣubḥ-i-Azal", Luvah: Journal of the Creative Imagination, Summer 2013, p. 1-37, ISSN 2168-6319.

- (FR) Fabrizio Frigerio, "Un prisonnier d'État à Chypre sous la domination ottomane : Soubh-i-Ezèl à Famagouste", in: Πρακτικά του Γ Διεθνούς Κυπρολογικού Συνέδριου (Atti del III Congresso Internazionale di Studi Ciprioti), Nicosia, Cipro, 2001, vol. 3, p. 629-646.

- (EN) Denis MacEoin, "Division and authority claims in Babism (1850-1866)", in: Studia iranica, Paris, t. 18, fasc. 1, 1989, pp. 93–129.

- (EN) Denis MacEoin, The Sources for Early Bābī Doctrine and History, E.J. Brill, Leiden, 1992, ISBN 90-04-09462-8.

- (EN) William McCants e Kavian Milani, "The History and Provenance of an Early Manuscript of the Nuqtat al-kaf Dated 1268 (1851–52)", in: Iranian Studies, Settembre 2004, volume 37, n. 3, p. 431-449.

- (EN) Manúchihrí Sipihr, "The Practice of Taqiyyah (Dissimulation) in the Babi and Bahai Religions", in: Research Notes in Shaykhi, Babi and Baha'i Studies",1999, v.3, n°3.

- (EN) Manúchihrí Sipihr, "The Primal Point's Will and Testament", in: Research Notes in Shaykhi, Babi and Baha'i Studies, 2004, v.7, n°2.

Voci correlate

Altri progetti

Wikimedia Commons contiene immagini o altri file su Ṣubḥ-i Azal

Wikimedia Commons contiene immagini o altri file su Ṣubḥ-i Azal

Collegamenti esterni

- (EN) "La religione del Bayan" sito dei seguaci attuali di Ṣubḥ-i Azal, con una fotografia, une biografia scritta da Atiyya Ruhi e l'albero genealogico di Ṣubḥ-i Azal.

- (EN) Blog azali.

- (EN) Blog di N. Wahid Azal, con delle fotografie e degli scritti di Subh-i-Azal, su wahidazal.blogspot.ch.

- (EN) Articolo sulla comunità del Bayán in Iran.

- (EN) "Il Testamento del Bab", successione del Bab, con commenti.

- (EN) William McElwee Miller Collection of Bābī Writings and Other Iranian Texts, 1846-1923, alla Princeton University Library.

| Controllo di autorità | VIAF (EN) 266910202 · ISNI (EN) 0000 0003 8276 5287 · CERL cnp01285859 · LCCN (EN) no2007069556 · GND (DE) 1011233010 |

|---|