Utente:Xavier121/Sandbox3

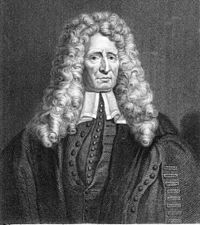

Frederik Ruysch (23 marzo, 1638 — 22 febbraio, 1731) è stato un botanico e anatomista olandese, ricordato per i suoi esperimenti sulla conservazione del tessuto umano e la creazione di diorami o modellini, costituiti da parti del copro umano.[1]

Biografia[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

Frederik Ruysch è nato a L'Aia (The Hague), figlio di un funzionario del governo e incominciò come allievio di un farmacista. Affascinato presto dall'anatomia comicniò a studiare all'università di Leiden, sotto la guida di Franciscus Sylvius. Suoi compagni di corso sono stati Jan Swammerdam, Reinier de Graaf e Niels Stensen. All'opoca, i corpi da sezionare erano molto scarsi e costosi, e Ruysch si trovò presto coinvolto nel cercare un modo per procurarsi gli organi. Nel 1661 sposò la figlia di un architetto olandese, di nome Pieter Post. Nel 1664 si laureò con una tesi sulla pleurite.[2] Ruysch divenne praelector della corporazione dei chirugica di Amsterdam nel 1667. L'anno successivo fu nominato capo istruttore del reparto ostetrico della città. Esse non erano più autorizzate a praticare la loro professione se non erano prima aesaminate dal Ruysch. In 1679 he was appointed as a forensic advisor to the Amsterdam courts and in 1685 as a professor in botany in the Hortus Botanicus Amsterdam, where he worked with Jan and Caspar Commelin. Ruysch specialized on the indigenous plants.

Ruysch researched many areas of human anatomy, and physiology, using spirits to preserve organs, and assembled one of Europe's most famous anatomical collections.[3] His chief skill in the preparation and preservation of specimens in a secret liquor balsamicum. In 1697 Peter the Great and Nicolaes Witsen visited Ruysch who had all the specimens exposed in five rooms, on two days during the week open for the public. He told Peter, who had a keen interest in science, how to catch butterflies and how to preserve them. They also had a common interest in lizards.[4] Together they went to see patients, and Ruysch taught him how to draw teeth.

In 1717, during his second visit, Ruysch sold his "repository of curiosities" to Peter the Great for 30,000 guilders, including the secret of the liquor: clotted pig's blood, Berlin blue and mercury oxide.[5] In her early years, his daughter Rachel Ruysch, a painter of still lifes, had helped him to decorate the collection with flowers, fishes, seashells and the delicate body parts with lace. Ruysch refused to help when everything had to be packed and labelled. It took Albert Seba more than a month. The 100 colli were not sent immediately, but because of the Great Nordic War in the year after, divided over two ships. The collection was intact, and the rumours about the sailors that drunk the alcohol, are untrue.

Ruysch immediately began anew in his house on Bloemgracht, in the Jordaan. After his death this collection was sold to August the Strong.[6] While some of his preserved collections remain, none of his scenes have survived. They are only known through a number of engravings, notably those by Cornelius Huyberts.

Ruysch came to recognition with his proof of valves in the lymphatic system, the Vomeronasal organ in snakes, and arteria centralis oculi (the central artery of the eye). Ruysch was painted by his son-in-law Jurriaen Pool. Frederik Ruysch published together with Herman Boerhaave.

Opere[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

- Disputatio medica inauguralis de pleuritide. Dissertation, Leiden, 1664.

- Dilucidatio valvularum in vasis lymphaticis et lacteis. Hagae-Comitiae, ex officina H. Gael, 1665; Leiden, 1667; Amsterdam, 1720. 2. Aufl. 1742.

- Museum anatomicum Ruyschianum, sive catalogus rariorum quae in Authoris aedibus asservantur. Amsterdam, 1691. 2. Aufl. 1721; 3. Aufl. 1737.

- Catalogus Musaei Ruyschiani. Praeparatorum Anatomicorum, variorum Animalium, Plantarum, aliarumque Rerum Naturalium. Amsterdam: Janssonio-Waesbergios, 1731.

- Observationum anatomico-chirurgicarum centuria. Amsterdam 1691; 2. Aufl. 1721: 3. Aufl. 1737.

- Epistolae anatomicae problematicae. 14 Bände. Amsterdam, 1696-1701.

- Thesaurus anatomicus. 10 Bände. Amstelaedami, Johan Wolters, 1701–1716.

- Adversarium anatomico-medico-chirurgicorum decas prima. Amsterdam 1717.

- Curae posteriores seu thesaurus anatomicus omnium precedentium maximus. Amsterdam, 1724.

- Curae renovatae seu thesaurus anatomicus post curas posteriores novus. Amsterdam, 1728.

- Thesaurus animalium primus. Amsterdam, 1728. 18: Amsterdam, 1710, 1725.

- Curae renovatae seu thesaurus anatomicus post curas posteriores novus. Amsterdam, 1733.

- Samen met Herman Boerhaave: Opusculum anatomicum de fabrica glandularum in corpore humano. Leiden, 1722; Amsterdam, 1733.

- Tractatio anatomica de musculo in fundo uteri. Amsterdam, 1723.

- Opera omnia. 4 Bände. Amsterdam, 1721.

- Opera omnia anatomico-medico-chirurgica huc usque edita. 5 Bände. Amsterdam, 1737.

Note[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

- ^ Frederik Ruysch's Anatomical Dioramas.

- ^ Dohmen, J. (1982) Wetenschappelijke erediensten voor publiek. De anatomische lessen van Frederik Ruysch. In: 1632- 1982. 350 Jaar wetenschap in Amsterdam. Folia Civitatis, 9 januari 1982, nr. 19. p. 19.

- ^ Israel, J.I (1995) The Dutch Republic: Its Rise, Greatness and Fall, 1477-1806, p. 907.

- ^ Driessen, J. (1996) Tsaar Peter de Grote en zijn Amsterdamse vrienden, p. 8.

- ^ Driessen-Van het Reve, J.J. (2006) De Kunstkamera van Peter de Grote. De Hollandse inbreng, gereconstrueerd uit brieven van Albert Seba en Johann Daniel Schumacher uit de jaren 1711-1752. English summary, p. 338.

- ^ Kapitel 6.

Collegamenti esterni[modifica | modifica wikitesto]

- (EN) Ole Daniel Enersen, Xavier121/Sandbox3, in Who Named It?.

- On his collection, in German

[[Category:1638 births]]

[[Category:1731 deaths]]

[[Category:Dutch anatomists]]

[[Category:Dutch botanists]]

[[Category:People from The Hague]]