Prosumer: differenze tra le versioni

Testo e note |

Inserita pagina prosumer EN |

||

| Riga 1: | Riga 1: | ||

{{hatnote|This article is about consumers who also produce. The term may also refer to [[wikt:prosumer#Etymology_2|prosumer equipment]].}}A '''prosumer''' is an individual who both [[:en:Consumption_(economics)|consumes]] and [[:en:Production_(economics)|produces]]. The term is a [[:en:Portmanteau|portmanteau]] of the words ''producer'' and ''consumer''. Research has identified six types of prosumers: DIY prosumers, self-service prosumers, customizing prosumers, collaborative prosumers, monetised prosumers, and economic prosumers.<ref name=":02">{{Cite journal|last=Lang|first=Bodo|last2=Dolan|first2=Rebecca|last3=Kemper|first3=Joya|last4=Northey|first4=Gavin|date=2020-01-01|title=Prosumers in times of crisis: definition, archetypes and implications|url=https://doi.org/10.1108/JOSM-05-2020-0155|journal=Journal of Service Management|volume=ahead-of-print|issue=ahead-of-print|doi=10.1108/JOSM-05-2020-0155|issn=1757-5818}}</ref> |

|||

Il '''Chilometro Zero''' in [[economia]] è un tipo di [[commercio]] nel quale i prodotti vengono commercializzati e venduti nella stessa zona di produzione.<ref name=":0">{{Cita web|url=http://km-zero-.html/|titolo=Cosa vuol dire chilometro zero quando si parla di cibo|sito=EXPONet|lingua=en|accesso=2021-03-31}}</ref> |

|||

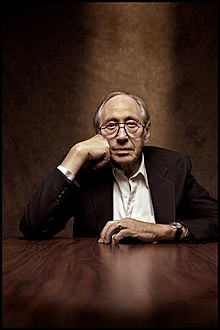

The terms ''prosumer'' and ''prosumption'' were coined in 1980 by American [[:en:Futurism|futurist]] [[:en:Alvin_Toffler|Alvin Toffler]], and were widely used by many technology writers of the time. Technological breakthrough and a rise in user participation blurs the line between production and consumption activities, with the consumer becoming a prosumer.<ref>Li, R.Y.M. (2018). Addictive manufacturing, prosumption and construction safety, in: An Economic Analysis on Automated Construction Safety, Springer [online] https://www.researchgate.net/search.Search.html?type=publication&query=Addictive%20manufacturing,%20prosumption%20and%20construction%20safety</ref> |

|||

La locuzione "a chilometri zero" in ambito [[Trasformazione agroalimentare|agroalimentare]] identifica una [[politica economica]] che predilige l'alimento locale, in contrapposizione all'alimento globale, e soprattutto risparmiando nel processo di trasporto del prodotto, in termini anche di [[inquinamento]].<ref>{{Cita libro|nome=Paolo|cognome=Castaldi|titolo=Chilometri zero : viaggio nell'Italia dell'economia solidale|url=|accesso=|data=2014|editore=BeccoGiallo|p=23|OCLC=908162644|ISBN=978-88-99016-07-4}}</ref> |

|||

== Definitions and contexts == |

|||

== La locuzione "a chilometri zero" == |

|||

[[File:Alvin_Toffler_02.jpg|link=https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Alvin_Toffler_02.jpg|miniatura|[[:en:Alvin_Toffler|Alvin Toffler]], coiner of the term "prosumer".]] |

|||

Prosumers have been defined as "individuals who consume and produce value, either for self-consumption or consumption by others, and can receive implicit or explicit incentives from organizations involved in the exchange."<ref name=":02" /> |

|||

The term has since come to refer to a person using [[:en:Commons-based_peer_production|commons-based peer production]]. |

|||

=== Industria automobilistica === |

|||

La locuzione "a chilometri zero" significa "che ha percorso, dal momento in cui è stato prodotto, zero chilometri", cioè nessun chilometro. In origine, essa si riferiva ad una particolare categoria di automobili, che i concessionari si autoimmatricolano e vendono ai clienti ad un prezzo ridotto del 20-25% rispetto a quello di mercato. Il vantaggio per il concessionario sta nel fatto che, comprando più autovetture di quante riesca a venderne in un certo periodo, è in grado di raggiungere un determinato volume di acquisti che gli garantisce sconti e altre agevolazioni da parte delle case produttrici. L'acquirente, a sua volta, compra un'auto praticamente nuova, che non ha mai viaggiato o ha viaggiato pochissimo (in genere, i chilometri non sono mai esattamente zero, ma non superano comunque i cento), al prezzo di un'auto usata.<ref name=":0" /> |

|||

In the digital and online world, ”prosumer” is used to describe 21st-century online buyers because not only are they consumers of products, but they are able to produce their own products such as, customised handbags, jewellery with initials, jumpers with team logos etc. |

|||

=== Prodotti agricoli === |

|||

Un'altra accezione, più recente, si riferisce ai prodotti agricoli: in questo caso, dicendo che un prodotto è "a chilometri zero" s'intende dire che, per arrivare dal luogo di produzione a quello di vendita e consumo, esso ha percorso il minor numero di chilometri possibile. L'idea di fondo, in sostanza, è quella di ridurre l'impatto ambientale che il trasporto di un prodotto comporta, in particolare l'emissione di anidride carbonica che va ad incrementare il livello d'inquinamento. |

|||

In the field of renewable energy, prosumers are households or organisations which at times produce surplus fuel or energy and feed it into a national (or local) distribution network; whilst at other times (when their fuel or energy requirements outstrip their own production of it) they consume that same fuel or energy from that grid. This is widely done by households by means of PV panels on their roofs generating electricity. Such households may additionally make use of battery storage to increase their share of self-consumed PV electricity, referred to as prosumage in the literature.<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Schill|first1=Wolf-Peter|last2=Zerrahn|first2=Alexander|last3=Kunz|first3=Friedrich|date=2017-06-01|title=Prosumage of solar electricity: pros, cons, and the system perspective|url=http://www.diw.de/documents/publikationen/73/diw_01.c.552031.de/dp1637.pdf|journal=Economics of Energy & Environmental Policy|language=en|volume=6|issue=1|doi=10.5547/2160-5890.6.1.wsch|issn=2160-5882|hdl=10419/149900}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last=Green Iain Staffell|first=Richard|date=2017-06-01|title='Prosumage' and the British Electricity Market|journal=Economics of Energy & Environmental Policy|language=en|volume=6|issue=1|doi=10.5547/2160-5890.6.1.rgre|issn=2160-5882|doi-access=free}}</ref> It is also done by businesses which produce biogas and feed it into a gas network while using gas from the same network at other times or in other places. The European Union’s Nobel Grid project, which is part of their Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme, uses the term in this way, for example. |

|||

Secondo questa filosofia risulta vantaggioso consumare prodotti locali in quanto accorciare le distanze significa aiutare l'ambiente, promuovere il patrimonio agroalimentare regionale e abbattere i prezzi, oltre a garantire un prodotto fresco, sano e stagionale. S'interrompe così quella catena che è nata con la grande distribuzione, che lavora con i grandi numeri, a scapito del rapporto consumatore-produttore. L'idea di prodotti "a chilometri zero", essendo sensibile alla riduzione delle energie impiegate nella produzione km0 si riferisce alle energie impiegate nel trasporto e non nella produzione, oltre a diminuire il tasso di anidride carbonica nell'aria porta ad un uso consapevole del territorio, facendo riscoprire al consumatore la propria identità territoriale attraverso i piatti della tradizione. È un modo di opporsi alla standardizzazione del prodotto, che provoca l'aumento della produttività facendo però perdere la diversità. |

|||

The [[:en:Sharing_economy|sharing economy]] is another context where individuals can act as prosumers. For example in the sharing economy, individuals can be providers (e.g., [[:en:Airbnb|Airbnb]] hosts, [[:en:Uber|Uber]] drivers) and consumers (e.g., Airbnb guests, Uber passengers). Prosumers are one avenue to grow the sharing economy.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Lang|first6=Jan|issn=1441-3582|doi=10.1016/j.ausmj.2020.06.012|language=en|journal=Australasian Marketing Journal (AMJ)|url=http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1441358220300604|title=How to grow the sharing economy? Create Prosumers!|date=2020-06-21|last6=Kietzmann|first=Bodo|first5=Rebecca|last5=Dolan|first4=Joya A.|last4=Kemper|first3=Jeandri|last3=Robertson|first2=Elsamari|last2=Botha|doi-access=free}}</ref> |

|||

Il sistema dei "chilometri zero" si esprime attraverso diversi canali: la modalità di vendita più diffusa è quella che si effettua tramite i distributori automatizzati, tipicamente situati nelle piazze o in altri luoghi pubblici. Molteplici sono gli spazi che vengono adibiti alla vendita diretta per gli agricoltori locali all'interno dei mercati comunali e rionali. |

|||

Le origini del marchio chilometro zero |

|||

Si chiama "progetto chilometro zero" (impropriamente, perché la forma corretta della locuzione dovrebbe essere "chilometri zero") l'operazione lanciata quando? Esiste un riferimento più preciso? da Coldiretti Veneto attraverso la quale si vogliono convincere gestori di pubbliche mense, chef e grande distribuzione a proporre ai consumatori preferibilmente prodotti stagionali del territorio. Si trovano giàquando? i mercatini agricoli distribuiti sul territorio di molte regioni italianequali?, soprattutto al nord, dove tipicità vengono vendute senza intermediazioni, niente imballaggio e nessun costo di conservazione. Ne è dimostrazione il successo dei distributori automatici di latte crudo esiste un riferimento per verificare l'autenticità dell'affermazione?, sempre più diffusi perché favoriscono l'acquisto consapevole consapevole di cosa? e la sicurezza del prodotto rintracciabile (la tracciabilità alimentare è requisito normativo sia per prodotti a km0 che per gli altri). Il Veneto è la regione che ha dato il via alla campagna per i "chilometri zero", divenendo una legge regionale, la n. 7 del 25 luglio 2008, la prima a livello nazionale nel suo genere. Le finalità di tale legge, espressamente dichiarate nell'articolo 1, sono di incentivare l'utilizzo di prodotti locali nelle attività ristorative affidate ad enti pubblici, incrementando in tale maniera la vendita diretta da parte degli imprenditori agricoli. |

|||

Scholars have connected prosumer culture to the concept of [[:en:McDonaldization|McDonaldization]], as advanced by sociologist [[:en:George_Ritzer|George Ritzer]]. Referring to the business model of [[:en:McDonald's|McDonald's]], which has emphasized efficiency for management while getting customers to invest more effort and time themselves (such as by cleaning up after themselves in restaurants), McDonaldization gets prosumers to perform more work without paying them for their labor.<ref>{{Citation|last=Chen|publisher=John Wiley & Sons, Ltd|editor2-last=Ryan|first2=George|last2=Ritzer|access-date=2021-04-19|isbn=978-1-118-98946-3|doi=10.1002/9781118989463.wbeccs167|language=en|place=Oxford, UK|first=Chih-Chin|editor-first=Daniel Thomas|editor-last=Cook|pages=1–3|work=The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Consumption and Consumer Studies|url=http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/9781118989463.wbeccs167|date=2015-03-24|title=McDonaldization|editor2-first=J Michael}}</ref> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

<references /> |

|||

== |

== Origins and development == |

||

The blurring of the roles of consumers and producers has its origins in the cooperative [[:en:Self-help|self-help]] movements that sprang up during various economic crises, e.g. the [[:en:Great_Depression|Great Depression]] of the 1930s. [[:en:Marshall_McLuhan|Marshall McLuhan]] and Barrington Nevitt suggested in their 1972 book ''Take Today'', (p. 4) that with electric technology, the consumer would become a producer. In the 1980 book, ''[[:en:The_Third_Wave_(Toffler_book)|The Third Wave]]'', [[:en:Futurologist|futurologist]] [[:en:Alvin_Toffler|Alvin Toffler]] coined the term "prosumer" when he predicted that the role of producers and [[:en:Consumer|consumers]] would begin to blur and merge (even though he described it in his book ''[[:en:Future_Shock|Future Shock]]'' from 1970). Toffler envisioned a highly saturated [[:en:Marketplace|marketplace]] as [[:en:Mass_production|mass production]] of [[:en:Standardization|standardized]] products began to satisfy basic consumer demands. To continue growing [[:en:Profit_(economics)|profit]], businesses would initiate a process of [[:en:Mass_customization|mass customization]], that is the mass production of highly customized products. |

|||

{{Cita libro|titolo=Hello}} |

|||

However, to reach a high degree of customization, consumers would have to take part in the production process especially in specifying [[:en:Design|design]] requirements. In a sense, this is merely an extension or broadening of the kind of relationship that many affluent clients have had with professionals like [[:en:Architect|architects]] for many decades. However, in many cases architectural clients are not the only or even primary end-consumers.<ref>Lorimer, A. 'Prosumption Architecture: The Decentralization of Architectural Agency as an Economic Imperative', H+ Magazine, 2014, [online] http://hplusmagazine.com/2014/01/13/prosumption-architecture-the-decentralisation-of-architectural-agency-as-an-economic-imperative/ [04/02/14]</ref> |

|||

Toffler has extended these and many other ideas well into the 21st-century. Along with more recently published works such as ''[[:en:Revolutionary_Wealth|Revolutionary Wealth]]'' (2006), one can recognize and assess both the concept and fact of the ''prosumer'' as it is seen and felt on a worldwide scale. That these concepts are having global impact and reach, however, can be measured in part by noting in particular, Toffler's popularity in [[:en:China|China]]. Discussing some of these issues with [[:en:Newt_Gingrich|Newt Gingrich]] on [[:en:C-SPAN|C-SPAN]]'s ''[[:en:After_Words|After Words]]'' program in June 2006, Toffler mentioned that ''The Third Wave'' is the second ranked bestseller of all time in China, just behind a work by [[:en:Mao_Zedong|Mao Zedong]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.trumix.com/podshows/521309|title=C-SPAN - After Words created. Toffler interviewed by Gingrich Episode|publisher=[[C-SPAN]]|date=June 6, 2006|access-date=December 5, 2008|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090126051635/http://www.trumix.com/podshows/521309|archive-date=January 26, 2009}}</ref> |

|||

[[:en:Don_Tapscott|Don Tapscott]] reintroduced the concept in his 1995 book ''The Digital Economy.'', and his 2006 book ''[[:en:Wikinomics|Wikinomics: How Mass Collaboration Changes Everything]]'' with Anthony D. Williams. [[:en:George_Ritzer|George Ritzer]] and Nathan Jurgenson, in a widely cited article, claimed that prosumption had become a salient characteristic of [[:en:Web_2.0|Web 2.0]]. Prosumers create value for companies without receiving wages. |

|||

Toffler’s Prosumption was well described and expanded in economic terms by [[:en:Philip_Kotler|Philip Kotler]], who saw them as a new challenge for marketers.<ref>Kotler, Philip. (1986). Prosumers: A New Type of Customer. Futurist(September–October), 24-28.</ref> Kotler anticipated that people will also want to play larger role in designing certain goods and services they consume, furthermore modern computers will permit them to do it. He also described several forces that would lead to more prosumption like activities, and to more sustainable lifestyles, that topic was further developed by Tomasz Szymusiak in 2013 and 2015 in two marketing books.<ref>Szymusiak T., (2013). Social and economic benefits of Prosumption and Lead User Phenomenon in Germany - Lessons for Poland [in:] Sustainability Innovation, Research Commercialization and Sustainability Marketing, Sustainability Solutions, München. {{ISBN|978-83-936843-1-1}}</ref><ref>Szymusiak T., (2015). Prosumer – Prosumption – Prosumerism, OmniScriptum GmbH & Co. KG, Düsseldorf. {{ISBN|978-3-639-89210-9}}</ref> |

|||

Technological breakthrough has fastened the development of prosumption. With the help of additive manufacturing techniques, for example, co-creation takes place at different production stages: design, manufacturing and distribution stages. It also takes place between individual customers, leading to co-design communities. Similarly, mass customisation is often associated with the production of tailored goods or services on a large scale production. This increase in participation has flourished following the increasing popularity of [[:en:Web_2.0|Web 2.0]] technologies, such as Instagram, Facebook, Twitter and Flickr. |

|||

In July 2020, an academic description reported on the nature and rise of the "robot prosumer", derived from [[:en:Technology#Medieval_and_modern_history_(300_CE_%E2%80%93_present)|modern-day technology]] and related [[:en:Participatory_culture|participatory culture]], that, in turn, was substantially predicted earlier by [[:en:List_of_science_fiction_authors|science fiction writers]].<ref name="EA-20200724">{{cite news|author=Lancaster University|author-link=Lancaster University|title=Sci-fi foretold social media, Uber and Augmented Reality, offers insights into the future - Science fiction authors can help predict future consumer patterns.|url=https://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2020-07/lu-sfs072420.php|date=24 July 2020|work=[[EurekAlert!]]|access-date=26 July 2020}}</ref><ref name="JCC-20200723">{{cite journal|last=Ryder|first=M.J.|title=Lessons from science fiction: Frederik Pohl and the robot prosumer|date=23 July 2020|journal=[[Journal of Consumer Culture]]|doi=10.1177/1469540520944228|url=https://eprints.lancs.ac.uk/id/eprint/138821/1/FINAL_Frederik_Pohl_and_the_robot_prosumer.pdf}}</ref><ref name="LU-20200726">{{cite journal|last=Ryder|first=Mike|title=Citizen robots:biopolitics, the computer, and the Vietnam period|url=https://eprints.lancs.ac.uk/id/eprint/141870/|date=26 July 2020|journal=[[Lancaster University]]|access-date=26 July 2020}}</ref> |

|||

== Criticism == |

|||

Prosumer [[:en:Capitalism|capitalism]] has been criticized as promoting "new forms of exploitation through [[:en:Unpaid_work|unpaid work]] [[:en:Gamification|gamified]] as fun".<ref name="JemielniakPrzegalinska20202">{{cite book|author1=Dariusz Jemielniak|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=yLDMDwAAQBAJ|title=Collaborative Society|author2=Aleksandra Przegalinska|date=18 February 2020|publisher=MIT Press|isbn=978-0-262-35645-9}}</ref>{{Rp|57}} |

|||

== Examples == |

|||

{{prose|date=November 2020}}{{unreferenced section|date=November 2020}}Identifiable trends and movements outside of the mainstream economy that have adopted prosumer terminology and techniques include: |

|||

* a ''Do It Yourself'' ([[:en:DIY|DIY]]) approach as a means of economic self-sufficiency or simply as a way to survive on diminished income |

|||

* the [[:en:Open_source_software|open source software]] movement creates software on their own, prime example is the successful [[:en:Operating_system|operating system]] [[:en:Linux|Linux]] which now dominates the server domain |

|||

* [[:en:Fablab|Fablab]] movement, self-fabrication capabilities especially [[:en:3d_printing|3d printing]] |

|||

* the [[:en:Voluntary_simplicity|voluntary simplicity]] movement that seeks personal, social, and environmental goals through prosumer activities such as: |

|||

** growing one's own food |

|||

** repairing clothing and appliances rather than buying new items |

|||

** playing musical instruments rather than listening to recorded music |

|||

* use of new media-creation and distribution technologies to foster independent, open, non-profit, "consumer-to-consumer" media and cultures (see [[:en:Wikipedia|Wikipedia]], [[:en:Independent_Media_Center|Indymedia]], most of [[:en:Creative_Commons|Creative Commons]]); many involved in independent media reject [[:en:Popular_culture|mass culture]] generated by [[:en:Concentration_of_media_ownership|concentrated corporate media]] |

|||

* self-sufficient [[:en:Barter_(economics)|barter]] networks, notably in [[:en:Developing_nations|developing nations]], such as Argentina's [[:en:Red_Global_de_Clubes_de_Trueque_Multirecíproco|RGT]] have adopted the term prosumer<sup>[[:en:Prosumer#External_links|4]]</sup> |

|||

* [[:en:YouTuber|YouTuber]] |

|||

== See also == |

|||

* [[:en:Creative_consumer|Creative consumer]] |

|||

* [[:en:Read/write_culture|Read/write culture]] |

|||

* [[:en:Cost_the_limit_of_price|Cost the limit of price]] |

|||

* [[:en:Participatory_culture|Participatory culture]] |

|||

* [[:en:Power_user|Power user]] |

|||

* [[:en:Produsage|Produsage]] |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

{{Reflist|30em}} |

|||

== References == |

|||

* Chen, Katherine K. (April 2012). "[http://abs.sagepub.com/content/56/4/570.abstract Artistic Prosumption: Cocreative Destruction at Burning Man]." ''American Behavioral Scientist'' Vol. 56, No. 4, 570-595. |

|||

* Kotler, Philip. (1986). Prosumers: A New Type of Customer. Futurist(September–October), 24-28. |

|||

* Kotler, Philip. (1986). The Prosumer Movement. A New Challenge for Marketers. Advances in Consumer Research, 13, 510-513. |

|||

* Lui, K.M. and Chan, K.C.C. (2008) Software Development Rhythms: Harmonizing Agile Practices for Synergy, John Wiley and Sons, {{ISBN|978-0-470-07386-5}} |

|||

* Michel, Stefan. (1997). Prosuming-Marketing. Konzeption und Anwendung. Bern; Stuttgart;Wien: Haupt. |

|||

* Nakajima, Seio. (April 2012). "[http://abs.sagepub.com/content/56/4/550.short Prosumption in Art]." ''American Behavioral Scientist'' Vol. 56, No. 4, 550–569. |

|||

* Ritzer, G. & Jurgenson, N., 2010. Production, Consumption, Prosumption. Journal of Consumer Culture, 10 (1), pp. 13 –36. |

|||

* Toffler, Alvin. (1980). The third wave: The classic study of tomorrow. New York, NY: Bantam. |

|||

* Xie, Chunyan, & Bagozzi, Richard P. (2008). Trying to Prosume: Toward a Theory of Consumers as Co-Creators of Value. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 36 (1), 109-122. |

|||

* Szymusiak T., (2013). Social and economic benefits of Prosumption and Lead User Phenomenon in Germany - Lessons for Poland [in:] Sustainability Innovation, Research Commercialization and Sustainability Marketing, Sustainability Solutions, München. {{ISBN|978-83-936843-1-1}} |

|||

* Szymusiak T., (2015). Prosumer – Prosumption – Prosumerism, OmniScriptum GmbH & Co. KG, Düsseldorf. {{ISBN|978-3-639-89210-9}} |

|||

== External links == |

|||

{{wiktionary}} |

|||

* [http://www.worldwidewords.org/turnsofphrase/tp-pro4.htm Turns of Phrase: Prosumer] - business-oriented definitions of producer/professional and consumer |

|||

Versione delle 17:52, 20 apr 2021

Template:HatnoteA prosumer is an individual who both consumes and produces. The term is a portmanteau of the words producer and consumer. Research has identified six types of prosumers: DIY prosumers, self-service prosumers, customizing prosumers, collaborative prosumers, monetised prosumers, and economic prosumers.[1]

The terms prosumer and prosumption were coined in 1980 by American futurist Alvin Toffler, and were widely used by many technology writers of the time. Technological breakthrough and a rise in user participation blurs the line between production and consumption activities, with the consumer becoming a prosumer.[2]

Definitions and contexts

Prosumers have been defined as "individuals who consume and produce value, either for self-consumption or consumption by others, and can receive implicit or explicit incentives from organizations involved in the exchange."[1]

The term has since come to refer to a person using commons-based peer production.

In the digital and online world, ”prosumer” is used to describe 21st-century online buyers because not only are they consumers of products, but they are able to produce their own products such as, customised handbags, jewellery with initials, jumpers with team logos etc.

In the field of renewable energy, prosumers are households or organisations which at times produce surplus fuel or energy and feed it into a national (or local) distribution network; whilst at other times (when their fuel or energy requirements outstrip their own production of it) they consume that same fuel or energy from that grid. This is widely done by households by means of PV panels on their roofs generating electricity. Such households may additionally make use of battery storage to increase their share of self-consumed PV electricity, referred to as prosumage in the literature.[3][4] It is also done by businesses which produce biogas and feed it into a gas network while using gas from the same network at other times or in other places. The European Union’s Nobel Grid project, which is part of their Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme, uses the term in this way, for example.

The sharing economy is another context where individuals can act as prosumers. For example in the sharing economy, individuals can be providers (e.g., Airbnb hosts, Uber drivers) and consumers (e.g., Airbnb guests, Uber passengers). Prosumers are one avenue to grow the sharing economy.[5]

Scholars have connected prosumer culture to the concept of McDonaldization, as advanced by sociologist George Ritzer. Referring to the business model of McDonald's, which has emphasized efficiency for management while getting customers to invest more effort and time themselves (such as by cleaning up after themselves in restaurants), McDonaldization gets prosumers to perform more work without paying them for their labor.[6]

Origins and development

The blurring of the roles of consumers and producers has its origins in the cooperative self-help movements that sprang up during various economic crises, e.g. the Great Depression of the 1930s. Marshall McLuhan and Barrington Nevitt suggested in their 1972 book Take Today, (p. 4) that with electric technology, the consumer would become a producer. In the 1980 book, The Third Wave, futurologist Alvin Toffler coined the term "prosumer" when he predicted that the role of producers and consumers would begin to blur and merge (even though he described it in his book Future Shock from 1970). Toffler envisioned a highly saturated marketplace as mass production of standardized products began to satisfy basic consumer demands. To continue growing profit, businesses would initiate a process of mass customization, that is the mass production of highly customized products.

However, to reach a high degree of customization, consumers would have to take part in the production process especially in specifying design requirements. In a sense, this is merely an extension or broadening of the kind of relationship that many affluent clients have had with professionals like architects for many decades. However, in many cases architectural clients are not the only or even primary end-consumers.[7]

Toffler has extended these and many other ideas well into the 21st-century. Along with more recently published works such as Revolutionary Wealth (2006), one can recognize and assess both the concept and fact of the prosumer as it is seen and felt on a worldwide scale. That these concepts are having global impact and reach, however, can be measured in part by noting in particular, Toffler's popularity in China. Discussing some of these issues with Newt Gingrich on C-SPAN's After Words program in June 2006, Toffler mentioned that The Third Wave is the second ranked bestseller of all time in China, just behind a work by Mao Zedong.[8]

Don Tapscott reintroduced the concept in his 1995 book The Digital Economy., and his 2006 book Wikinomics: How Mass Collaboration Changes Everything with Anthony D. Williams. George Ritzer and Nathan Jurgenson, in a widely cited article, claimed that prosumption had become a salient characteristic of Web 2.0. Prosumers create value for companies without receiving wages.

Toffler’s Prosumption was well described and expanded in economic terms by Philip Kotler, who saw them as a new challenge for marketers.[9] Kotler anticipated that people will also want to play larger role in designing certain goods and services they consume, furthermore modern computers will permit them to do it. He also described several forces that would lead to more prosumption like activities, and to more sustainable lifestyles, that topic was further developed by Tomasz Szymusiak in 2013 and 2015 in two marketing books.[10][11]

Technological breakthrough has fastened the development of prosumption. With the help of additive manufacturing techniques, for example, co-creation takes place at different production stages: design, manufacturing and distribution stages. It also takes place between individual customers, leading to co-design communities. Similarly, mass customisation is often associated with the production of tailored goods or services on a large scale production. This increase in participation has flourished following the increasing popularity of Web 2.0 technologies, such as Instagram, Facebook, Twitter and Flickr.

In July 2020, an academic description reported on the nature and rise of the "robot prosumer", derived from modern-day technology and related participatory culture, that, in turn, was substantially predicted earlier by science fiction writers.[12][13][14]

Criticism

Prosumer capitalism has been criticized as promoting "new forms of exploitation through unpaid work gamified as fun".[15]57

Examples

Template:ProseTemplate:Unreferenced sectionIdentifiable trends and movements outside of the mainstream economy that have adopted prosumer terminology and techniques include:

- a Do It Yourself (DIY) approach as a means of economic self-sufficiency or simply as a way to survive on diminished income

- the open source software movement creates software on their own, prime example is the successful operating system Linux which now dominates the server domain

- Fablab movement, self-fabrication capabilities especially 3d printing

- the voluntary simplicity movement that seeks personal, social, and environmental goals through prosumer activities such as:

- growing one's own food

- repairing clothing and appliances rather than buying new items

- playing musical instruments rather than listening to recorded music

- use of new media-creation and distribution technologies to foster independent, open, non-profit, "consumer-to-consumer" media and cultures (see Wikipedia, Indymedia, most of Creative Commons); many involved in independent media reject mass culture generated by concentrated corporate media

- self-sufficient barter networks, notably in developing nations, such as Argentina's RGT have adopted the term prosumer4

- YouTuber

See also

- Creative consumer

- Read/write culture

- Cost the limit of price

- Participatory culture

- Power user

- Produsage

Notes

- ^ a b Bodo Lang, Prosumers in times of crisis: definition, archetypes and implications, in Journal of Service Management, ahead-of-print, ahead-of-print, 1º gennaio 2020, DOI:10.1108/JOSM-05-2020-0155.

- ^ Li, R.Y.M. (2018). Addictive manufacturing, prosumption and construction safety, in: An Economic Analysis on Automated Construction Safety, Springer [online] https://www.researchgate.net/search.Search.html?type=publication&query=Addictive%20manufacturing,%20prosumption%20and%20construction%20safety

- ^ (EN) Prosumage of solar electricity: pros, cons, and the system perspective (PDF), in Economics of Energy & Environmental Policy, vol. 6, n. 1, 1º giugno 2017, DOI:10.5547/2160-5890.6.1.wsch.

- ^ (EN) Richard Green Iain Staffell, 'Prosumage' and the British Electricity Market, in Economics of Energy & Environmental Policy, vol. 6, n. 1, 1º giugno 2017, DOI:10.5547/2160-5890.6.1.rgre.

- ^ (EN) Bodo Lang, How to grow the sharing economy? Create Prosumers!, in Australasian Marketing Journal (AMJ), 21 giugno 2020, DOI:10.1016/j.ausmj.2020.06.012.

- ^ (EN) Chih-Chin Chen, McDonaldization, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 24 marzo 2015, pp. 1–3, DOI:10.1002/9781118989463.wbeccs167.

- ^ Lorimer, A. 'Prosumption Architecture: The Decentralization of Architectural Agency as an Economic Imperative', H+ Magazine, 2014, [online] http://hplusmagazine.com/2014/01/13/prosumption-architecture-the-decentralisation-of-architectural-agency-as-an-economic-imperative/ [04/02/14]

- ^ C-SPAN - After Words created. Toffler interviewed by Gingrich Episode, su trumix.com, C-SPAN, June 6, 2006.

- ^ Kotler, Philip. (1986). Prosumers: A New Type of Customer. Futurist(September–October), 24-28.

- ^ Szymusiak T., (2013). Social and economic benefits of Prosumption and Lead User Phenomenon in Germany - Lessons for Poland [in:] Sustainability Innovation, Research Commercialization and Sustainability Marketing, Sustainability Solutions, München. ISBN 978-83-936843-1-1

- ^ Szymusiak T., (2015). Prosumer – Prosumption – Prosumerism, OmniScriptum GmbH & Co. KG, Düsseldorf. ISBN 978-3-639-89210-9

- ^ Lancaster University, Sci-fi foretold social media, Uber and Augmented Reality, offers insights into the future - Science fiction authors can help predict future consumer patterns., in EurekAlert!, 24 July 2020.

- ^ M.J. Ryder, Lessons from science fiction: Frederik Pohl and the robot prosumer (PDF), in Journal of Consumer Culture, 23 July 2020, DOI:10.1177/1469540520944228.

- ^ Mike Ryder, Citizen robots:biopolitics, the computer, and the Vietnam period, in Lancaster University, 26 July 2020.

- ^ Collaborative Society, MIT Press, 18 February 2020, ISBN 978-0-262-35645-9.

References

- Chen, Katherine K. (April 2012). "Artistic Prosumption: Cocreative Destruction at Burning Man." American Behavioral Scientist Vol. 56, No. 4, 570-595.

- Kotler, Philip. (1986). Prosumers: A New Type of Customer. Futurist(September–October), 24-28.

- Kotler, Philip. (1986). The Prosumer Movement. A New Challenge for Marketers. Advances in Consumer Research, 13, 510-513.

- Lui, K.M. and Chan, K.C.C. (2008) Software Development Rhythms: Harmonizing Agile Practices for Synergy, John Wiley and Sons, ISBN 978-0-470-07386-5

- Michel, Stefan. (1997). Prosuming-Marketing. Konzeption und Anwendung. Bern; Stuttgart;Wien: Haupt.

- Nakajima, Seio. (April 2012). "Prosumption in Art." American Behavioral Scientist Vol. 56, No. 4, 550–569.

- Ritzer, G. & Jurgenson, N., 2010. Production, Consumption, Prosumption. Journal of Consumer Culture, 10 (1), pp. 13 –36.

- Toffler, Alvin. (1980). The third wave: The classic study of tomorrow. New York, NY: Bantam.

- Xie, Chunyan, & Bagozzi, Richard P. (2008). Trying to Prosume: Toward a Theory of Consumers as Co-Creators of Value. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 36 (1), 109-122.

- Szymusiak T., (2013). Social and economic benefits of Prosumption and Lead User Phenomenon in Germany - Lessons for Poland [in:] Sustainability Innovation, Research Commercialization and Sustainability Marketing, Sustainability Solutions, München. ISBN 978-83-936843-1-1

- Szymusiak T., (2015). Prosumer – Prosumption – Prosumerism, OmniScriptum GmbH & Co. KG, Düsseldorf. ISBN 978-3-639-89210-9

External links

- Turns of Phrase: Prosumer - business-oriented definitions of producer/professional and consumer